Navigation in the Amazon River Basin

Roberto Natali - December 5, 2021

* L’immagine di copertina di questo paper è stata presa dal sito di Terraria, nella sezione Foresta Tropicale, consultabile al seguente link: https://ivaldisergio1960.altervista.org/rio-delle-amazzoni/

Have you ever sailed on the Amazon River? Have you ever felt that sensation of immensity, strength, life, light, between infinite green, sounds of the forest and colorful parrots darting in the sky? The great South American river is life for the cities and populations that live along its course; it is a fascinating water reality but, above all, the Amazon River is strategic for the economies of the countries that border it. 6,180 km long - second in length only to the Nile with its 6,671 km - it crosses the vast Amazon rainforest (about 5.5 million km²) with a flow rate of 160,000 m3/sec., to then flow into the Atlantic Ocean.

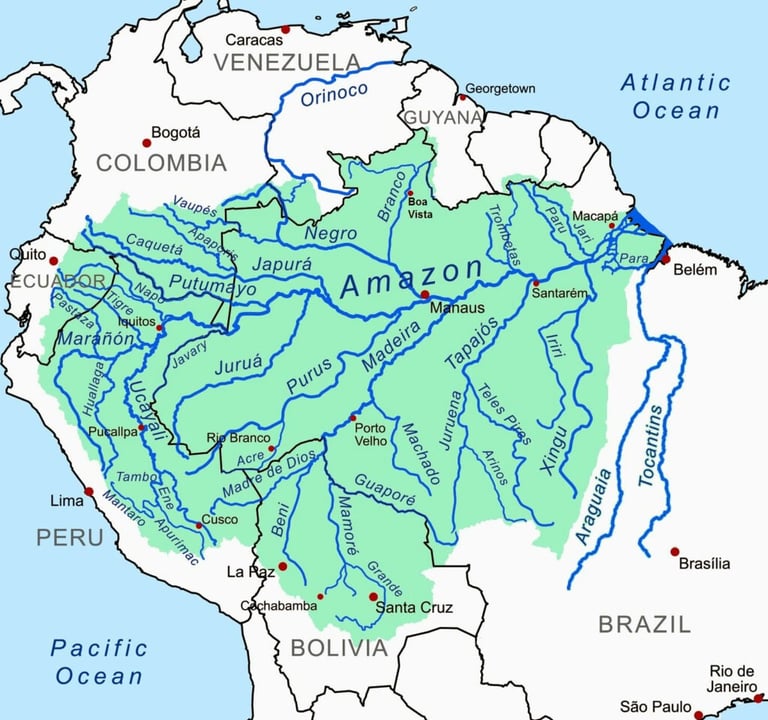

Fig. 1: Il Rio delle Amazzoni e tutti i suoi principali affluenti

In particular, the great importance of the Amazon River derives from the size and richness of its drainage basin, which covers an area of approximately 6,300,000 km², equivalent to 35.5% of the South American continent. It includes various regions (in addition to the vast Amazonian lowlands, part of the Pre-Andes, the South American plateau, part of the Guyana massif) and politically involves Brazil, Colombia, Ecuador, Bolivia, Peru, Venezuela, Guyana, Suriname and French Guiana. Its tributaries are numerous and, in turn, constitute truly impressive waterways and feed the largest existing rainforest, the main photosynthesis reserve on Earth, commonly known as the “lungs of the planet”. The enormous number and complexity of the maze of rivers that pour their waters into the Amazon River have made it difficult for European scholars to unequivocally determine the sources of the great South American river. In fact, there are source branches coming from various areas of the Andes mountain range. The main one is the Rio Ucayali, which for 1,600 km, crosses Peru from south to north receiving the waters of its main tributary, the spectacular Río Urubamba. It also receives the waters of rivers with suggestive names, often linked to the civilization of the Incas, such as the Río Apurímac, the Río Tambo, the Río Cohenga, the Río Sheshea, the Río Tapiche, and the Río Aguaytía.

Fig. 2: Rio Ucayali

Fig. 3: Rio Marañón

A Look at the Economy

It is difficult to overestimate the importance of the Amazon River, whose basin covers more than half of the world's remaining tropical forests, contains a tenth of the planet's tree species and, as natural resources, conceals immense potential. But precisely for this reason, large multinational companies continue to devastate the territory in search of high profits, becoming protagonists of a continuous ideological clash with global environmental groups. In reality, the exploitation of the forest and the transformation of the land for agricultural purposes, especially for livestock breeding, had already developed in the 1960s. The harvesting of rubber - an element at the base of the development of the great city of Manhaus already at the end of the nineteenth century - and of timber, transported through the immense network of rivers and canals, has always attracted producers and traders who in the past, until the arrival of synthetic plastic, had made real economic fortunes.

But today technology has greatly intensified the exploitation and destruction of the forest, as well as the pollution of waterways. More than 150 dams have been built (and just as many have been planned) to produce hydroelectric power along the 1,100 tributaries of the Amazon River, and more than 800 mines dot the banks of the great rivers for the collection and transport of the truly abundant mineral resources. The Amazon River and its tributaries, in fact, open up very important communication routes through the impenetrable rainforest. The depth of the water and the slowness of the current make the basin the most navigable river network in the world. The upper reaches of many rivers, however, remain less easy to navigate, due to the presence of rapids, sometimes violent, which constitute insurmountable obstacles for the transport of goods and materials. The Amazon River allows boats of significant tonnage to travel upriver to the Peruvian city of Iquitos, while small local boats, led by expert indigenous navigators, can use the innumerable river arteries for smaller transports.

Fig. 4: Bacino idrico del Rio delle Amazzoni

Even today, livestock farming is still significant, initially limited to the needs of farmers (especially Brazilians), then becoming the protagonist of a strong expansion, thanks to the impetus of multinational companies. But it should be considered that in order to intensively raise a few tens of thousands of cattle, hundreds of thousands of hectares of forest have been burned. Furthermore, many industries have been set up in the vast Amazon region: tire factories in the state of Parà, not far from the port of Belem; and then wood, latex, tropical fruit, oils and seeds are produced and exploited economically. It should not be ignored, however, that the potential for development of the transport network is far from optimal. In fact, if the waterways - at least in the lower section - are generally navigable, the areas between the rivers are difficult to access. In fact, air transport is too expensive and even an expansion of the railway network, completely insufficient, would present prohibitive costs. The Brazilian state, therefore, began a policy in the 1970s to build trans-Amazon roads, traced through the forest. But some of them present problems that cannot be eliminated, including the need to keep them constantly clean in an environment with a lot of lush vegetation, the obstacle of the numerous rivers and their bends, the hostility of the indigenous populations who inhabit the territories crossed. It must also be said that these phenomena do not allow the economic potential of the region to be fully exploited, which is why the economy actually records limited productivity in the various sectors.

Fig. 5: Il Rio delle Amazzoni che si snoda nella fitta vegetazione

Environmental Problems

We have mentioned the importance of the Amazon basin for terrestrial ecology, the well-known problem of progressive deforestation in that area of the world and the damage it causes to the planet's biodiversity, as well as the fact that the majestic Amazon River and its large tributaries are not immune, unfortunately, from the serious problems that affect the environment. Consider, for example, that the water vapor produced by the rivers and the immense Amazon vegetation is an essential element for the redistribution of rainfall and heat from the sun. In this regard, it is worth remembering that the growing concern about climate change and the more than evident increase in temperature on earth has sparked a strong debate on the commercial use of the Amazon and its river basin and the need to protect these precious environmental realities. The rate of deforestation has slowed slightly, but continues.

It is estimated that today - compared to a base year identified in 1970 - more than 20% of the Amazon basin has been deforested and some scientific assessments indicate that by 2030, deforestation could reach 30%. Such an eventuality would risk seriously modifying the rate of precipitation in the region, reducing its defenses, with an evident impact also on the flow of its waterways. The "state of health" of the Amazon River and its large tributaries therefore remains worrying, also because the superlative extension of the Amazon basin gives the region a special function as a reserve of animal and plant species. Suffice it to say that the majority of the freshwater fish on the entire planet live in the Amazon rivers and, as shown by studies carried out for decades in French Guiana, thousands of new species of insects, fungi and plants never noticed and recorded before have been discovered on the foliage of the very tall trees of the forest.

On the other hand, pollution of the rivers deriving from chemical products is also a serious concern. An example is provided by the vast soy monocultures that heavily use toxic products capable of polluting the soil for very long periods. Furthermore, although rarely, some serious accidents have resulted from oil spills in Amazonian areas rich in hydrocarbons that – despite the precautions taken – have caused the pouring of enormous masses of crude oil into waterways with consequent oily waves that are deadly for numerous species of fish and other animals that feed in the rivers. Furthermore, Spanish scholars, with the financial support of National Geographic, have conducted research and a chemical monitoring campaign in the Amazon region (“Pharmaceuticals and other urban contaminants threaten Amazonian freshwater ecosystems”) that has provided important evidence, confirming a significant risk for the biodiversity of the freshwaters of the region. Especially in the vicinity of the four large Brazilian cities – Manaus, Belém, Santarém, Macapá – and other urban areas that have grown rapidly in recent years, the discharge of wastewater into Amazonian waterways – 90% without pretreatment – containing chemicals, cosmetics, medicines, hormones and other urban contaminants has been recorded. The impairment of the ecological quality of rivers (particularly the Río Negro, the Tapajós and the Tocatins) can obviously have long-term effects on aquatic species in the Amazon River and its tributaries, causing a loss of biodiversity that should be protected.

Fig. 6: Effetti di spill over sul fiume, sulla vegetazione e sulle popolazioni locali

Legal elements

Many territories and nations depend on the use of rivers for their development plans; the search for an efficient and productive use of waterways, especially in terms of navigation, can occasionally lead to legal (and non-legal) disputes between States interested in the waterways regarding the exercise of their rights. For this reason, even in the Amazon area, the various States have had to recognize the importance of establishing and respecting common rules on the use of international rivers, in order to facilitate coexistence, cooperation and economic development. Many of these rules refer to free navigation. Written rules on the subject and the crystallization of customs have given rise to the creation of the so-called "International River Law", of which free navigation is a part.

The issue of freedom of navigation on rivers has ancient roots, because it contains an evident strategic value. Already in ancient Rome, the free use of rivers for the benefit of all citizens of the Empire for the purposes of navigation and fishing was in force; but this practice was abolished in the Middle Ages by feudal lords who claimed absolute power over the stretches of rivers that crossed their possessions, imposing tolls and tariffs on ships and transported goods and reserving exclusively to their subjects free navigation in the river area under their control. Subsequently, Hugo Grotius – considered by many to be the father of international law – proclaimed in 1625 the right of free navigation on navigable rivers, arguing that tariffs and tolls should not be imposed for the transport of goods and materials from one State to another. However, a concrete political movement in favor of free circulation began only in the 19th century and the Congress of Vienna in 1815 confirmed the basic principles of international river law.

In the case of the South American continent, the principle of free navigation on waterways did not develop through the common recognition of a principle of law. In fact, free navigation in the Amazon river system – as well as in those of the Orinoco, the Río de la Plata and other large rivers in the region – originated from the internal legislation of the States that allowed it, or from bilateral agreements signed for mutual interests. The policy of the South American States, in fact, consisted in the mere concession of navigation permission to other States, on a voluntary basis. In essence, unlike Europe, there are no regulatory bodies for international river navigation in South America, just as there are no obligations (except for express bilateral agreements) to allow vessels flying the flags of other States on the rivers of the national territory.

Fig. 7: Estensione della foresta amazzonica

The set of national decisions has nevertheless led to a system of multilateral agreement, consisting of the Amazon Cooperation Treaty, signed in Brasilia in July 1978 by the Republics of Bolivia, Brazil, Colombia, Ecuador, Guyana, Peru, Suriname and Venezuela, with the aim of promoting development, environmental protection, and rational use of the natural resources of their territories. Free river navigation on the Amazon River is an important part of this agreement, which aims to promote river communications between the territories of the States Parties and the Atlantic Ocean. But it should be noted that even in the Amazon Cooperation Treaty, Brazil has maintained the position according to which freedom of navigation on international rivers depends on the consent of the State in which the navigation takes place.

Conclusions

The AB AQUA study center highlights the strategic value of the subjects it analyzes. Even in the case of the Amazon River and its important and numerous tributaries, in fact, it is important to underline how they are able to exercise a primary influence on the geographical, social, economic, political and environmental reality of the States that are crossed by them. And with this a significant influence is also marked on the degree of their development, demographic growth and level of industrialization. In other words, this fascinating hydrographic area, which includes almost seven million km² and contains a fifth of the world's fresh water resources, crossing numerous countries constitutes an element of great strategic value, since in addition to a vast navigation space and source of energy, it remains a natural source of progress and development of peoples. For these reasons, we consider equally strategic and necessary an ever greater commitment of the entire International Community to protect with conviction the fantastic and precious catchment area of the Amazon River.

Abaqua

Via Cassia, 615

00189 Roma (RM)

© 2024. All rights reserved.

Codice Fiscale: 96584590580