Jacopo Belli - January 20, 2026

The Geopolitical Scenarios Of Submarine Cables

Introduction

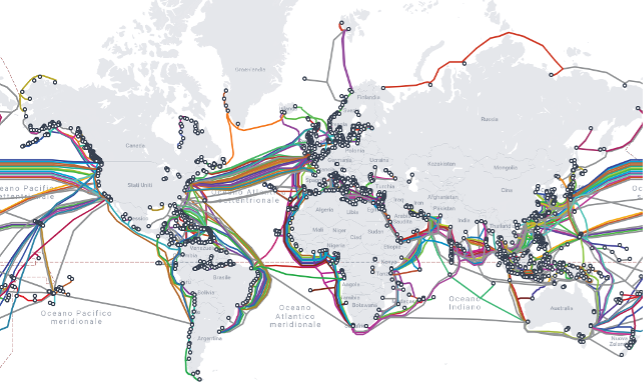

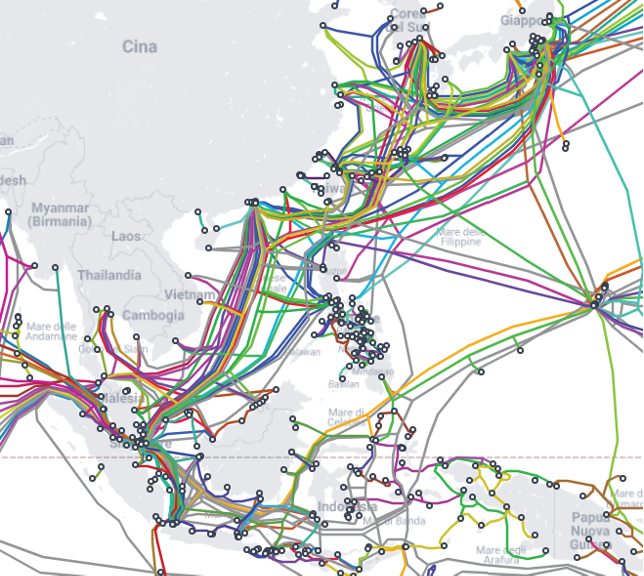

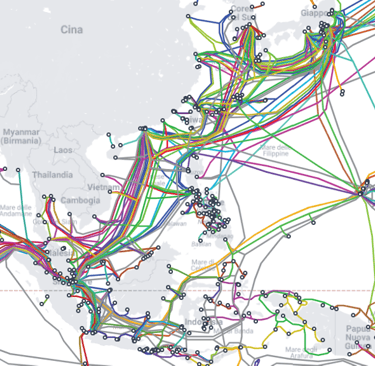

The network of submarine cables constitutes the invisible physical infrastructure upon which nearly all global digital connectivity relies. Optical fibers cross oceans and seas for distances estimated at approximately 1.4 and 1.7 million kilometers, respectively, connecting continents and ensuring the operation of the digital infrastructures that underpin the Internet, cloud services, global finance, and communications.[1] More than 95% of international internet and voice traffic is carried through these cables. These digital backbones have acquired the status of critical strategic infrastructure, as they sustain global value chains, the stability of financial markets, and the functioning of everyday life.

Despite their vital role, their protection, surveillance, and governance remain inadequate. The infrastructure is often located in remote seabed areas and managed by private consortia, while public security responses are not fully aligned with their strategic importance. A 2022 study by the European Parliament’s Policy Department highlights that the European Union lacks a comprehensive overview of the ownership of marine infrastructure, as well as a centralized registry of routes and operators.[2]

In parallel, the international landscape emerging over the coming years, characterized by growing geopolitical competition, particularly linked to the control of critical infrastructure, is transforming the seabed into a new arena of informational power. Submarine cable systems are therefore becoming strategic bottlenecks, giving rise to competition over digital sovereignty, as highlighted by Yale University in its 2024 study “Submarine Cables and the Risks to Digital Sovereignty.” The nature of submarine cables limits a state’s ability to regulate the infrastructure on which it depends, reduces data security, and threatens its capacity to deliver telecommunications services. States are currently addressing these challenges through regulatory controls on submarine cables and related companies, as well as by investing in the development of additional cabling infrastructure and in the security and protection of the cables themselves. Despite these efforts, the effectiveness of such mechanisms is undermined by significant obstacles stemming from technical limitations and the lack of international regulatory coordination. As noted in “Submarine Cables and the Risks to Digital Sovereignty,” these obstacles result in legal gaps that could be addressed through a more proactive governance framework for submarine cable infrastructure.[3]

In this context, the areas identified by the geopolitical mapping of thalassocracy often overlap and intersect with the routes of submarine cable networks.

For Italy, this transformation is of particular significance. Its geographic position at the heart of the Mediterranean basin, the presence of numerous cable landing points, and the emerging industrial capabilities in the fields of cable laying and subsea sensing provide a substantial strategic leverage. However, translating these advantages into a competitive edge requires integrated and coordinated national policies across technological, industrial, and security domains, aligned with the European vision of open strategic autonomy. The hydro-strategic analysis developed in this report, an area in which AB AQUA has been actively engaged for some time, takes as its starting point the assessment of data and vulnerabilities, moves through geopolitical competition and the regulatory framework, and ultimately develops operational options, while in its final section examining the infrastructural convergence of the Blue Economy and the Space Economy in order to identify Italy’s role within the European technological and strategic ecosystem.

The Backbone of Global Connectivity

Submarine infrastructure does not typically feature in the common perception of digital telecommunications; however, its importance becomes evident when considering that approximately 98% of digital telecommunications traffic travels through undersea backbones, and that one of the most technologically advanced countries in the Far East, Japan, relies on submarine cable infrastructure for 99% of its international communication services. These figures highlight how even a temporary disruption of a single submarine backbone can have unpredictable consequences for entire communities, leading to network slowdowns, service outages, and significant impacts on finance, industry, and communications.[4]

Submarine cables carry a wide range of traffic, from video streaming and voice communications to financial transactions. It is estimated that approximately ten trillion dollars in financial transactions flow through submarine cables every day.[5] Ownership, management, and protection of submarine cable routes contribute directly to the technological sovereignty of states, as effective control over such infrastructure implies a higher degree of strategic autonomy—an objective that becomes particularly salient when security rises to the top of major powers’ political agendas. Just as in Nicholas Spykman’s traditional geopolitical theories of thalassocracy, geography shapes the rules of economics and, consequently, politics, submarine cables similarly follow and intersect the world’s main strategic fault lines, converging where major international maritime routes cross and running through key maritime chokepoints.

This configuration entails a significant degree of vulnerability, as the areas where cables are laid are often highly congested and may traverse shallow seabed. Moreover, ownership of these cables is predominantly private and managed by operators and private consortia driven by economic interests, resulting in a form of logistical dependency linked to the availability of cable-laying and repair vessels, specialized components, and maintenance capabilities. These factors are compounded by physical and technical vulnerabilities, including damage caused by fishing and navigation activities, such as anchors and bottom trawling, as well as extraordinary natural events, including earthquakes and submarine landslides.

Image 1: Submarine Cable Map – World.

Fonte: TeleGeography Submarine Cable Map https://www.submarinecablemap.com/

Traditionally, most disruptions were caused by accidental events. More recently, however, a growing number of incidents indicate that submarine cable networks are becoming strategic targets: deliberate attacks, sub-threshold operations, and the control or sabotage of cables are now part of the emerging landscape of “hybrid warfare.” The sabotage of the Nord Stream pipeline in September 2022 brought the issue of potential vulnerabilities of submarine infrastructure to the forefront of the European debate, underscoring the urgent need to accelerate efforts to strengthen national capabilities and enhance the resilience of subsea assets. In this context, NATO has increased maritime patrols, surveillance activities, and exercises focused on the protection of underwater infrastructure. It has also established new mechanisms, such as the Maritime Centre for the Security of Critical Undersea Infrastructure and the Critical Undersea Infrastructure Coordination Cells, which have facilitated information sharing among Allies, partners, and key private-sector stakeholders.[6]

The strategic value of a submarine cable is defined by three fundamental dimensions: operational continuity, which ensures that data networks remain functional even in critical scenarios; deterrence, understood as the ability to demonstrate surveillance, repair, and rapid response capabilities in order to discourage attacks or sabotage; and technological autonomy, namely the capacity to develop, at the national or regional level, cable laying, maintenance, monitoring, and protection capabilities, thereby reducing dependence on global supply chains.

When these components are taken together, it becomes evident that submarine cables engage core levers of foreign policy, defense, and the national economy.

The Geography of Power of Submarine Telecommunications

The uncertainty of our time has information as its primary necessity, in order to extract meaning and identify the orientations required for its process of civilization. The importance of information, in an era in which infodemia[7] has become the term used to identify a tangible and concrete phenomenon and is therefore of primary importance. The physical components that sustain its diffusion, namely submarine cables, thus become the physical, rather than purely digital, territory of data geopolitics. Submarine backbones represent one of the principal connections linking the United States and Japan, and Japan’s dependence on stable digital connectivity is shaped by its insular geographic configuration, its role as a regional financial hub, its proximity to China in the context of its alliance with the United States, and its vulnerability to natural hazards that could threaten submarine routes.

For Japan, disruptions to submarine cables would have immediate economic and security consequences. The United States, in turn, integrates cable security into its broader Indo-Pacific strategy, linking the protection of infrastructure to alliance commitments and to efforts aimed at counterbalancing China’s technological reach. Japan’s strategic cooperation with the United States on submarine cable infrastructure reflects a significant effort to safeguard its digital sovereignty and to strengthen regional stability in response to rising geopolitical threats. Moreover, this cooperation has evolved not only into technical resources, but also into instruments of alliance-building.

China has strengthened its influence through the “Digital Silk Road,” financing and constructing new submarine cables through state-owned companies such as HMN Tech.[8] HMN Tech is one of the world’s leading manufacturers of submarine cables, benefiting from a model of close alignment between the state and industry, and it has also been expanding its presence in the cable repair market. These projects not only extend China’s commercial reach but also raise concerns among other states regarding surveillance, dependency, and the strategic leverage that Beijing could gain over global communications.

By contrast, the United States has actively sought to limit Chinese participation in major submarine cable projects, citing national security risks, and has coordinated with allies to ensure that new routes are built by trusted partners. At the same time, commercial competition is deeply intertwined with state interests. Chinese technology companies work in close coordination with government initiatives, while U.S.-based firms such as Google, Meta, and Amazon invest in private cable systems to secure faster and more autonomous data transfer between global data centers. Although driven primarily by commercial considerations, these private-sector projects often align with U.S. strategic objectives by strengthening control over key routes and limiting opportunities for Chinese companies to expand their influence.

As a result, submarine cables are increasingly becoming strategic assets underpinning the global economy, international security, and digital sovereignty, while also highlighting water as an indispensable strategic element.

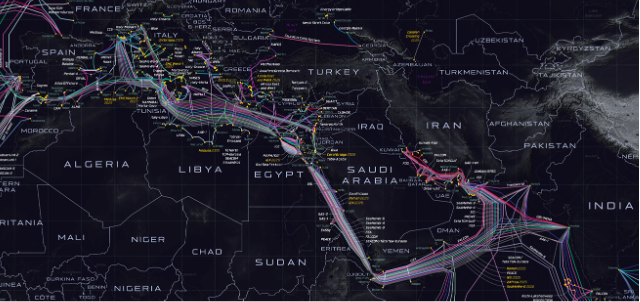

The Mediterranean and the Digital Rimland

When Nicholas Spykman formulated his Rimland theory in 1944, he identified the coastal fringes of Eurasia as the decisive arena of competition between land-based and maritime powers. U.S. thalassocratic strategy was grounded in these theoretical foundations. “Whoever controls these areas of contact controls Eurasia, and whoever controls Eurasia controls the destiny of the world.”[9]. Today, in the twenty-first century, that coastal belt has acquired a digital dimension: submarine cable backbones, energy and commercial routes, and surveillance networks overlap, giving rise to an informational Rimland. The wider Mediterranean, encompassing the Black Sea, the Red Sea, and the routes leading to the Indian Ocean, emerges as a digital hinge between continents. More than 20% of the world’s submarine cables pass through this region, concentrating flows of data and energy within a single interconnected infrastructure.[10]. This ancient crossroads, where for millennia people, goods, ideas, and cultures have intermingled (Braudel, 1986), now also intertwines communication and data infrastructures. More than 70 submarine cable systems, either operational or under construction, currently cross the Mediterranean hinge, with major landing points located in Italy, France, Spain, Greece, Israel, and Egypt.

Fonte: TeleGeography Submarine Cable Map. submarine-cable-map-2025.telegeography.com/

Projects such as 2Africa, AquaComms MedLink, BlueRaman, Medusa, and SEA-ME-WE 6 together form the map of tri-continental connectivity. In this process, Italy is directly involved as a landing point or interconnection hub for most of these backbones, enabled by its geographic position and thereby confirming its role as a digital hub of the Mediterranean.[11] This context underscores the need to make a sustained effort to maintain infrastructure resilience, given the close interconnection between maritime security and data security. The Italian Navy, through the National Underwater Dimension Hub (Polo Nazionale della Dimensione Subacquea – PNS), integrates the protection of submarine backbones into its maritime surveillance tasks. Italy is in fact exposed to vulnerabilities stemming from the concentration of cable landings in a limited number of coastal areas, such as Sicily, Calabria, and Apulia. Any disruption or sabotage in these regions would have immediate consequences not only for the country itself but also for the entire European network. The protection of these backbones therefore represents a key challenge not only for Italian sovereignty, but above all for European sovereignty.[12]

The EU Action Plan on Critical Undersea Infrastructure Security (2025) explicitly recognizes the need to strengthen the resilience of submarine cables in the Mediterranean and to promote dedicated European industrial value chains, outlining a comprehensive and multi-layered approach to the security of undersea infrastructure based on the full resilience cycle (prevention, detection, response, recovery, and deterrence). The Plan acknowledges that submarine cables constitute a systemic critical infrastructure, whose vulnerability may have immediate effects on the functioning of European economies, energy security, global connectivity, and the daily lives of citizens. The rationale for the Action Plan arises primarily from recent incidents, particularly in the Baltic Sea, which can no longer be interpreted as accidental or isolated events, but rather as potential hybrid campaigns aimed at exploiting legal ambiguities, fragmented competences, and difficulties of attribution. In this sense, the Action Plan strengthens the Union’s role in strategic coordination, while reaffirming the primary responsibility of Member States for the protection of critical infrastructure. The inherent dynamics of a multi-headed Europe inevitably require a nuanced diplomatic approach, capable of providing strategic direction without encroaching upon national policies. Accordingly, the Plan promotes common risk-assessment standards, coordinated stress tests, and a shared mapping of existing and planned infrastructure. Particular attention is devoted to strategic dependencies, especially along supply chains and about non-EU operators and suppliers.

On the operational front, the Plan promotes integrated surveillance mechanisms at the level of maritime basins, based on the fusion of civilian and military data, the use of space-based systems, subsea sensors, and “smart cable” technologies. The objective is the early detection of incidents and the reduction of plausible deniability, typical of hybrid operations, thereby enhancing attribution capabilities and, consequently, the deterrent value of European action.

The response and recovery dimension is also of particular importance. The Plan identifies the shortage of specialized vessels, trained crews, and spare components as one of the main bottlenecks in European resilience and proposes, in the longer term, the creation of an EU Cable Vessels Reserve Fleet, as well as strategic stockpiling and the standardization of components. Finally, the EU Action Plan places submarine cable security within a broader geopolitical framework, strengthening links with NATO, the use of counter-hybrid threat instruments, and the development of a genuine form of “cable diplomacy” with partners and third countries.

Crisis Scenarios

Subsea infrastructure has become a domain of sub-threshold competition, where clandestine operations, “plausibly deniable” incidents, and hybrid coercive actions can generate systemic effects without crossing the threshold of armed conflict. In response, NATO has established a Maritime Centre for the Security of Critical Undersea Infrastructure within MARCOM (Northwood), with the aim of enhancing situational awareness and strengthening deterrence in the undersea domain.[13] Italian military doctrine explicitly identifies seabed warfare as a new frontier between hybrid warfare and conventional conflict, with particular attention devoted to submarine cables and pipelines.[14]

Traditionally, the majority of disruptions stem from accidental causes, such as anchors, bottom trawling, and maritime or meteorological events, but the boundary with intentionality is often blurred: water depth, fragmented ownership structures, and lengthy investigation timelines make attribution particularly difficult.

In the Baltic Sea, in October 2023, Finland and Estonia recorded simultaneous damage to the Balticconnector gas pipeline and to telecommunications cables; subsequent investigations explored scenarios involving dragged anchors and potential criminal conduct, leading to legal proceedings against members of a tanker’s crew in 2025. Sweden also confirmed damage to a submarine cable between Sweden and Estonia caused by external force or tampering, triggering inter-agency coordination. In the same area, in 2024, two telecommunications cables were damaged within a forty-eight-hour period—one between Finland and Germany and the other between Sweden and Lithuania—fueling suspicions of sabotage as an act of hybrid warfare.

In January 2025, NATO deployed a coordinated group of warships as part of an operation named Baltic Sentry, with the specific objective of deterring attacks against undersea infrastructure. The Alliance also conducts an annual multinational maritime exercise, Freezing Winds.

Fonte: MIMIT, Scenari Geopolitici dei Cavi Sottomarini, Antonio Deruda

Similar dynamics are also emerging in the Indo-Pacific, where Taiwan has reported repeated incidents of damage to submarine cables amid intensifying strategic competition with China.

Following earlier accusations in 2023 related to disruptions of connections with the Matsu Islands, in February 2025 Taiwanese authorities detained a cargo vessel with a Chinese crew suspected of deliberately damaging a telecommunications cable. The indictment of the ship’s captain in the following April represents a significant precedent, as it translates a suspected act of sabotage into formal judicial action. Nevertheless, the operational ambiguity typical of “grey-zone” strategies and Beijing’s continued denial of responsibility continue to complicate the political and strategic attribution of such acts.[15]

Fonte: TeleGeography Submarine Cable Map https://www.submarinecablemap.com/

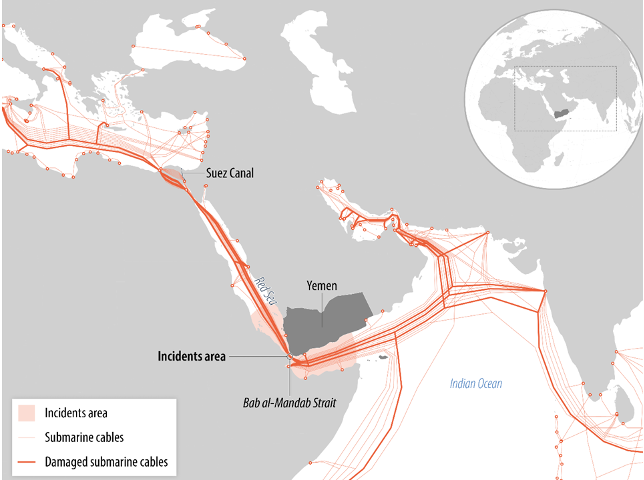

In the Red Sea, the Bab el-Mandeb Strait represents a critical crossroads for data routes connecting Europe, Africa, and Asia. Along the seabed of this maritime corridor runs a relatively limited number of fiber-optic cables, approximately sixteen, through which a significant share of global data traffic, estimated at around 17%, is transmitted. This high level of infrastructural concentration makes the Red Sea corridor a critical and highly vulnerable node in international digital connectivity. On 24 February 2024, the rupture of three submarine cables slowed regional connectivity, highlighting the vulnerability of the Suez–Mediterranean corridor in a context marked by Houthi attacks on maritime traffic and congested seabed conditions. In 2024, commercial volumes through the strait declined by approximately 50% due to the perceived risks stemming from regional instability, with operational implications also affecting cable repair vessels, which faced significant challenges in operating safely..[16]

Fonte: Compiled by EPRS from ArcGIS Undersea telecom cables and BBC.

The recent evolution of connectivity infrastructure in the Arctic introduces a new category of regional crisis scenarios. As highlighted by the Final Report on Arctic Connectivity Study (DPA, 2025), the Arctic is rapidly transforming from a peripheral area into an alternative strategic corridor for data transmission between Europe, Asia, and North America, through new submarine and hybrid backbones along polar routes. This transformation substantially alters the geography of risk, as Arctic infrastructure operates in extreme environments characterized by severe climatic conditions, unstable seabeds, seismic activity, and significant operational constraints on maintenance and repair. In this context, even a technical failure or an unintentional disruption can quickly escalate into a prolonged connectivity crisis, with restoration times significantly longer than those associated with temperate routes. The Arctic’s structural vulnerability therefore acts as a risk multiplier, particularly in scenarios of geopolitical tension, as the unavailability of a polar backbone reduces the overall redundancy of the global system, diverting traffic volumes onto already congested choke points such as the Mediterranean, the Suez Canal, or the North Atlantic.[17]

Conclusioni

The analysis conducted highlights how the subsea domain has become one of the new frontiers of geopolitical competition, not only because of the value of the infrastructure that traverses it, but also due to the intrinsically hybrid nature of the dynamics unfolding within it. Submarine cables, together with energy pipelines, environmental monitoring systems, and future sea–space hybrid networks, embody a dimension of power that eludes traditional categories of territorial sovereignty, operating in a space where public and private interests, security and commerce, peace and conflict increasingly overlap. In this context, water evolves from a natural resource into a global political element, intersecting multiple types of international crises and cutting across the major global critical issues in which it manifests itself as competition, pressure, and influence that are difficult to regulate through existing legal and diplomatic instruments.

The growing frequency of ambiguous events involving subsea infrastructure, as well as the expansion of connectivity networks in sensitive regions such as the wider Mediterranean and the Arctic, underscores the inadequacy of approaches based solely on security or deterrence. The dynamics shaping the subsea domain are inherently hybrid: they combine environmental, technological, economic, and strategic factors, generating systemic effects that transcend national and regional boundaries. In the absence of a shared institutional framework, these grey zones risk becoming arenas of permanent competition, where ambiguity fuels latent escalation and undermines global stability.

In light of these considerations, there is a clear need to complement security policies with a genuine water diplomacy, understood as a structured and permanent domain of international cooperation. Such a diplomacy should be endowed with global institutional standing and capable of integrating the protection of critical infrastructure, the sustainable management of marine ecosystems, and the regulation of economic and technological activities taking place beneath the sea surface. This approach would enable a systemic response to the hybrid dynamics characterizing the subsea domain, reducing uncertainty, strengthening mechanisms of attribution and conflict prevention, and promoting shared standards of responsible behavior.

For Italy and the European Union, investing in water diplomacy means safeguarding critical infrastructure and vital flows while contributing to the construction of a more stable international order, one in which control of the subsea domain is governed by a multilateral framework capable of reconciling security, cooperation, and shared responsib

_________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________

[1] Mauldin A., “Do Submarine Cables Account for 99% of Intercontinental Data Traffic?” TeleGeography,

May 4, 2023, https:// blog.telegeography.com/2023-mythbusting-part-3.

[2] European Parliament Policy Department for External Relations, Security threats to undersea communications cables and infrastructure – consequences for the EU, PE 702.557, April 2022.

[3] Ganz, A., Camellini, M., Hine, E. et al. Submarine Cables and the Risks to Digital Sovereignty. Minds & Machines 34, 31 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11023-024-09683-z

[4] CSIS - Center for Strategic & International Studies (2025) “The Strategic Future of Subsea Cables: Japan Case Study”.

[5] Doug Brake, “Submarine Cables: Critical Infrastructure for Global Communications”, ITIF, April 2019.

[6] Koshino Yuka (2024) The Changing Submarine Cables Landscape, EUISS – European Union Institute for Security Studies.

[7] Diffusione di una quantità eccessiva di informazioni, talvolta anche inaccurate, che rendono complesso orientarsi in modo conciso su un determinato argomento per la difficoltà di individuare fonti affidabili.

[8] Runde, D. F., Murphy, E. L., & Bryja, T. (2024). Safeguarding Subsea Cables: Protecting Cyber Infrastructure amid Great Power Competition. Csis.org.

[9] Spykman N. J., (2024) The Geography of the Peace, Oxford University Press, reprint.

[10] European Parliament Policy Department, (2022) Security Threats to Undersea Communications Cables, PE 702.557.

[11] NATO CMRE – La Spezia, (2024) Maritime Infrastructure and Information Dominance Workshop Report.

[12] Ministero della Difesa, (2025) Polo Nazionale della Dimensione Subacquea – Linee Strategiche 2025.

[13] European Commission (2023), Press Release.

[14] Marina Militare (2024) Rivista Marittima, Mensile della Marina Militare dal 1868

[15] Murphy E. L. (2025) Redundancy, Resiliency, and Repair. Securing Subsea Cable Infrastructure

[16] European Parliament (2024) Recent threats in the Red Sea

[17] Murphy E. L. (2025) Redundancy, Resiliency, and Repair. Securing Subsea Cable Infrastructure

Abaqua

Via Cassia, 615

00189 Roma (RM)

© 2024. All rights reserved.

Codice Fiscale: 96584590580