Chennai Water Crisis (2019). An Indian National Emergency

Filippo Verre - September 7, 2022

* L’immagine di copertina di questo paper è stata presa dal sito Scroll.in, consultabile al seguente link: https://scroll.in/latest/927307/tamil-nadu-reels-under-water-crisis-it-firms-and-hotels-in-chennai-severely-hit-by-shortage

In 2019, the Indian metropolis of Chennai – called Madras until 1996 when it adopted its current name – was the scene of a very serious water crisis that led local authorities to declare, on June 19, the much-feared “Day Zero”. For the first time in recent human history, a vast urban agglomeration of several million people had run out of water. No more water came out of the taps, manufacturing and industrial activities – of which Chennai is extremely rich – had no access to fresh water, the most basic of resources, too often taken for granted. Fortunately, following heavy rains between July and September of the same year, the Indian city avoided further drought-related problems. The rainfall resolved a very dangerous situation that was slowly sliding towards a socioeconomic crisis of massive proportions not only for the urban area of Chennai but for all of India. The metropolis, in fact, in addition to representing the sixth demographic entity of the Indian subcontinent, is a strategic hub from an industrial, technological and economic point of view at a national level. As a result, a crisis that initially seemed to have a local impact, quickly acquired broader relevance, to the point of becoming a real national emergency for what concerns the second most populous country in the world.

The causes of the water crisis

As often happens with crises of this magnitude, a series of environmental and human causes have caused the water emergency in Chennai. On that occasion, the lack of rainfall, heat waves and negligence by the city authorities in the management of water resources have laid the foundations for a situation that has held the Indian metropolis in check for many months.

In the three-year period 2016-2018, the monsoon rainfall that constitutes the main source of supply for Tamil Nadu[1] (the Indian state of which Chennai is the capital) has been very scarce. In 2018, in particular, rainwater had a decidedly weak impact on the city, since only 343.7 mm of rain fell compared to an average of 757.6 mm, thus resulting in a deficit of about 55%[2]. In fact, the entire state experienced a particularly aggressive dry season that year, with rainfall deficits of 23%. Thus, although to a lesser extent than its capital, a year before the water crisis that hit Chennai, the whole of Tamil Nadu was subjected to significant hardship.

Fig.2: Lo Stato indiano del Tamil Nadu

https://www.mapsofindia.com/maps/tamilnadu/tamilnadu-district.htm

Shortly before the water crisis, in addition to the low rainfall, severe heat waves compromised the fragile environmental balance of Chennai, which was already severely deteriorated by the lack of rain. The intense heat suffered in Tamil Nadu during the recent dry seasons has seriously affected the level of supply sources that the civilian population could rely on. For example, consider the case of the Chennai wetlands. Until recently, the metropolis was surrounded by many marshy territories. These were undoubtedly unhealthy areas from a hygienic-sanitary point of view; however, the high rate of marshiness was an indication of high humidity in the region. The intense heat waves that occurred between 2016 and 2018 contributed to visibly drying out the land and the atmosphere of Tamil Nadu. As evidence of this, we note the result of a scientific research carried out by Care Earth Trust, an NGO that deals with the preservation of biodiversity. According to researchers, Chennai’s wetlands are now a pale shadow of what they once were. The overall percentage of wetlands in the city’s geography has gone from a substantial 80% (in the late 1990s) to a paltry 15%. The final thinning of the wetter layer in Chennai’s peripheral areas occurred precisely in conjunction with the great heat and lack of rainfall, the main environmental causes of the water disaster that hit the Indian metropolis in the first half of 2019.

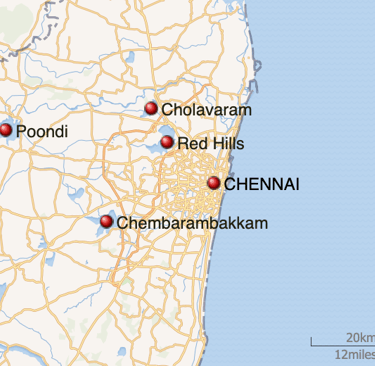

In line with the drying up of the wetlands, during the months preceding the crisis, the city’s main freshwater reserves also suffered a worrying decline. Chennai is normally supplied by four large reservoirs – Poondi, Cholavaram, Red Hills and Chembarambakkam – from which citizens daily draw the water resources needed to conduct daily activities. The lack of rain during the first months of 2019 was added to the little water that had fallen during the previous three years. All this put the four city reserves under severe water stress. In addition, the authorities' careless management of urban construction contributed to greatly worsening the situation.

Fig. 3: Le principali riserve idriche di Chennai

https://www.cnn.com/2019/06/20/world/chennai-satellite-images-reservoirs-water-crisis-trnd/index.html

Over time, the explosive growth of the city's population - which today exceeds 11 million people - has inevitably compromised Chennai's water supply. To make room for the new inhabitants, whose number grows every year at a dizzying rate, the authorities have built roads, neighborhoods and residences in areas previously used for the transit or storage of water. In this regard, take the case of the Poondi reservoir, the city's main reservoir. To make room for the apartments to be allocated to the new inhabitants, the Chennai authorities have progressively reduced its surface area, thus contributing to weakening a strategic water reserve for the city's water supply. In addition to the unwise building management, there are reports of unknowingly dangerous individual behaviors that many citizens of Chennai have engaged in over the last few years. In fact, many of the city's inhabitants have made do over time by building wells and activating autonomous pumping, with the result that the most superficial aquifers have inevitably dried up. Rainwater is also collected individually by millions of containers positioned on the roofs of the metropolis, with the worrying result that the resource fallen from the sky is actually consumed even before it hits the ground. In this way, the aquifers located under the city never replenish.

The impact of the water crisis on the population and on the city's economy was very heavy. Almost all productive activities first suffered increases due to the increase in the price of water and, subsequently, actual interruptions in production. Restaurants and hotels were among the first activities to be directly affected by the lack of water. Subsequently, industry and commerce were inevitably affected as well. To make matters worse, several thousand tankers containing the precious liquid found elsewhere poured into the chaotic streets of the city, adding to the inconvenience and confusion in a dry and turbulent metropolis. The scenes are the same as those that occurred in the spring of 2018 in Cape Town, another large metropolis that found itself grappling with a serious water crisis that we previously studied. Rationing, social tensions, fights to access a few liters of water, precarious hygienic-sanitary conditions and violence of various kinds were the most common factors during the period March-June 2019, when the large Indian metropolis was on the brink of a sociopolitical crisis of vast proportions.

Fig. 4: Fila per l’approvvigionamento d’acqua durante la crisi idrica di Chennai (maggio 2019)

https://timesofindia.indiatimes.com/city/chennai/why-chennais-water-crisis-should-worry-you/articleshow/69899842.cms

The economic importance of Chennai in the Indian production and industrial context

Every water crisis represents a serious problem that the authorities must try to remedy as quickly as possible. The inconveniences that the lack of fresh water causes to human communities, even small ones, are many and often not immediately resolvable. Only the providential intervention of the rains, as occurred both for Cape Town in 2018 and for Chennai in 2019, can interrupt the spiral of drought, tensions and suffering into which urban agglomerations often fall when they find themselves without water. The damage on a local basis caused by a water crisis is huge, quantifiable both in terms of the stress to which citizens are subjected and in terms of economic-productive aspects, given that most activities are interrupted due to the absence of the precious “blue gold”. Then, when one of the most economically important cities in India is hit, as in the case of Chennai, the situation takes on a macroscopic importance, making the negative effects of the crisis felt not only at a local level but in the national economic-productive context.

There are many sectors of absolute importance in which Chennai excels, starting from industrial production, passing through the hospitality-tourism sector to arrive at the technological one. As mentioned above, according to the 2011 Indian census, Chennai is the sixth most populous city in the country and constitutes the fourth largest metropolitan area. This means that, indirectly, the people who live, work or gravitate around the metropolis are more than fifteen million. Considered by the British colonizers to be extremely strategic from a geographical point of view - so much so that it was nicknamed "the gateway of South India" - today the city attracts highly qualified labor from every part of the country. This is because, by virtue of a very high number of residents, Chennai is today the fifth productive area of India, a tangible sign of the high number of development opportunities that can be found by working there.

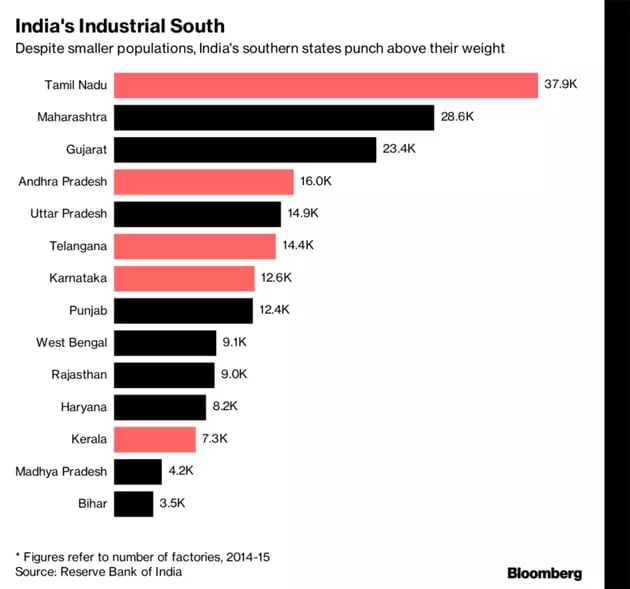

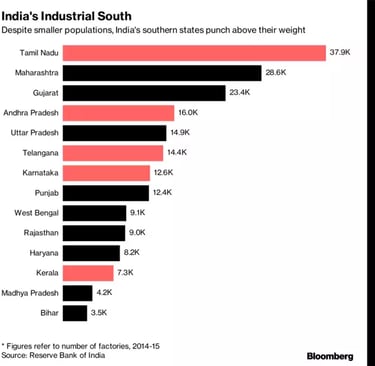

Fig. 5: rilevanza industriale del Tamil Nadu nel contesto produttivo indiano (2014-2015)

https://economictimes.indiatimes.com/industry/auto/indias-detroit-chennai-struggles-as-new-states-become-growth-drivers/articleshow/61940163.cms?from=mdr

As mentioned above, Tamil Nadu is not one of the most populous states in the Indian subcontinent. There are just over 72 million residents, mostly concentrated in the capital or in the surrounding areas. However, Chennai has a first-rate industrial apparatus, with the automotive sector as its spearhead. A significant part of Indian automobile production is carried out in the industries of the former Madras. In fact, the city is home to approximately 40% of the automotive industry and 45% of the automotive components industry based in New Delhi. Moreover, a large number of Western and Asian companies, including Royal Enfield, Hyundai, Renault, Nissan Motors, Yamaha Motor, Ford, BMW, Citroën and Mitsubishi have production plants in Chennai. All this has earned it the nickname "Indian Detroit" [3].

In addition to this, there is a thriving healthcare industry present in the capital of Tamil Nadu that attracts patients from all over the country. Given the presence of cutting-edge facilities and highly specialized medical personnel, over 40% of Indian health tourism has Chennai as its destination[4]. In addition, the metropolis is also a great attraction on a cultural level, being one of the most visited cities in all of India. In 2019 – in a pre-pandemic scenario, therefore – Chennai was ranked thirty-sixth in the global ranking of the most desired travel destinations in the world, with numbers also growing. A few years earlier, in 2015, the capital of Tamil Nadu had in fact ranked forty-third in the same ranking[5]. These data tell us how much potential this great city has not only in the local Indian context but also in the global panorama in terms of tourist attraction.

Also with regard to technology, Chennai is at the highest levels and represents a pole of attraction of absolute importance. Many software and IT services companies have development centers in Chennai, with production chains that have ramifications throughout Tamil Nadu. In the two-year period 2006-2007, the city contributed 14% of India's total software exports, making it the second largest exporter after Bangalore, the capital of the southeastern state of Karnataka, bordering Tamil Nadu to the west. Since 2012, Chennai has consolidated its technology production, effectively becoming a hub that attracts young computer engineers from all over the world. As evidence of this, it should be noted that Chennai's Tidel Park, completed in 2000, has been classified as the largest Information Technology (IT) park in Asia[6]. It is therefore no coincidence that the main international software companies have chosen this metropolis as the headquarters of their Indian branches.

The data analyzed so far certify the absolute centrality of Chennai in the production sector of New Delhi. It is therefore easy to understand the impact that the 2019 water crisis had not only in Tamil Nadu, but throughout the nation. It is therefore evident that the lack of water causes the almost immediate interruption of most of the productive activities present in a region. The paralysis for several months of the key sectors of Chennai has had a serious impact on the Indian productive chain which, as highlighted above, in terms of technology, health and automotive relies on Tamil Nadu and especially on its capital. In essence, therefore, if on a local level the human and economic hardships of the crisis have been very significant, with repercussions still present in the poorest neighborhoods of the city where the supply of fresh water is still precarious, also on the national front the water crisis has left a clear mark.

Conclusion

As noted above, in mid-July 2019, Chennai’s water crisis ended thanks to heavy rainfall that quickly mitigated the harmful effects of the prolonged drought. However, the inconvenience for the large city community did not end completely. The violent rains that fell almost without respite for over two months until the end of September caused the metropolis to plunge into another water emergency, in this case, however, caused not by a lack of water but by its excessive abundance. The land, made arid after many months of drought, was not able to contain the massive flows that quickly poured into the chaotic city streets. This, mockingly, then caused further problems for the already tested population of Chennai, who in a short time found themselves forced to manage another crisis in a flood context.

The lesson paid dearly by the capital of Tamil Nadu in 2019 must not leave us indifferent. In fact, there are many large cities – both in Asia and elsewhere – that are in a condition of high water-environmental risk. In India alone, there are 21 cities, including Chennai, that could exhaust their water reserves in a few years. According to Niti Ayog, a government think tank for public policy, over one hundred million people across the country could be directly involved in phenomena related to the lack of fresh water in the near future. A huge number that, according to some observers, would even be conservative. In this regard, Pradip Burman, an Indian environmentalist and entrepreneur trained in the United States, has warned the authorities in New Delhi about the catastrophic consequences of short-sighted management of national water resources. In his words:

“The second most populous country in the world has no data and plans to address climate change. We have the Chennai water crisis in front of us to prove it. Isn’t it time to intervene to safeguard the environment[7]?”

India, with its explosive demography, represents an interesting laboratory – albeit at times dramatic – to be analyzed from a hydro-strategic perspective. The planning of cities, increasingly urbanized and chaotic, must be as water-friendly as possible. It is not enough, in fact, to intervene a posteriori with emergency measures that can even worsen the situation. The tankers circulating on the streets of Chennai during the crisis, for example, did not solve much of the serious inconvenience suffered by the population but, on the contrary, contributed to generating confusion and tension. The management of plastic and waste will also necessarily have to be improved by the Indian authorities. Always taking inspiration from the 2019 water crisis, the two rivers that cross the capital of Tamil Nadu – the Koovam that passes through the center and the Adyar that flows further south – contributed to increasing the inconvenience of many millions of citizens during the heavy rains that occurred between July and September. This is because these are extremely polluted waterways that, in the event of a flood, pour a truly worrying amount of dirt downstream. The exponential growth of the world population, together with the progressive mass urbanization that sees the most striking cases in Asia, forces us to reconsider our "idea" of a city and to reorient it towards the canons of sustainable development and water security. Otherwise, by continuing to favor uncontrolled urban growth, we run the risk of repeating in a worrying way the mistakes already made in the past.

___________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________

[1] Il Tamil Nadu, con una popolazione che supera i 72 milioni di individui, è lo Stato più meridionale dell’India. Non è trai più vasti (130.000 km quadrati) ma ha storicamente ricoperto un ruolo strategico sul piano geografico.

[2] https://it.globalvoices.org/2019/09/una-forte-crisi-idrica-colpisce-chennai-in-india/.

[3] I dati sula produzione automobilistica indiana e sull’interesse occidentale ed asiatico ad investire nel settore locale sono consultabili presso questo link: https://economictimes.indiatimes.com/industry/auto/indias-detroit-chennai-struggles-as-new-states-become-growth-drivers/articleshow/61940163.cms?from=mdr.

[4] Maggiori informazioni sul numero di pazienti indiani che scelgono di curarsi presso le strutture sanitarie di Chennai sono consultabili al seguente link: http://www.indiahealthvisit.com/chennai-health-capital.htm.

[5] Questi dati sono stati presi analizzando la ricerca “Top 100 City Destinations – 2019 Edition”, consultabile al seguente link: http://go.euromonitor.com/rs/805-KOK-719/images/wpTop100Cities19.pdf.

[6] Maggiori dettagli sul Tidel Park e sulla grande industria tecnologica di Chennai sono reperibili al seguente link: https://web.archive.org/web/20020130201321/http://www.hindu.com/2000/11/02/stories/04022231.htm.

[7] https://it.globalvoices.org/2019/09/una-forte-crisi-idrica-colpisce-chennai-in-india/.

Abaqua

Via Cassia, 615

00189 Roma (RM)

© 2024. All rights reserved.

Codice Fiscale: 96584590580