Water Colonization: The Case of Cyprus

Filippo Verre - December 19, 2021

* L’immagine di copertina di questo paper è stata presa dal sito dell’European Space Agency (ESA), consultabile al seguente link: https://www.esa.int/Space_in_Member_States/Italy/Immagine_EO_della_Settimana_Cipro

Water scarcity is undoubtedly one of the major problems affecting Cyprus. As is known, the political and administrative situation of the island is not particularly simple, since since 1974 Cyprus has been effectively divided into two separate entities. The southern part, with a Greek majority, with Nicosia as its capital and a member of the European Union, is opposed to the northern part, with a Turkish majority and not recognized by the International Community[1]. However, despite this complex institutional framework, it is precisely the chronic lack of water resources that negatively characterizes the life of the Cypriots. The dry climate, the weak rainfall and the lack of adequate hydrographic basins make this corner of the eastern Mediterranean a difficult territory. Furthermore, in the last fifty years the situation has significantly worsened, due to the spread of mass tourism throughout the island. The construction of mega resorts, beach resorts and accommodation facilities, with the consequent exponential increase in tourist presences, has almost completely dried up the already poorly supplied aquifers with which the island is equipped. Furthermore, apart from small streams that flow from the Troodos mountain range, located in the central part, the waterways present in Cyprus are nothing more than winter streams that dry up during the hot periods. Among the most important rivers are the Diarrizos, whose mouth is near Kouklia (ancient Paphos), the Kouris that flows into the Mediterranean near the village of Episkopi located in the Limassol district and the Pideas that has its sources on the northern slopes of Macharia.

One of the remedies to deal with the notable water shortage that afflicts the island is to bring the precious liquid from other destinations. In the past, between 1998 and 2002, a system was studied in this sense: for about 4 years the fresh water was transported by sea using large tankers. However, the water needs of the local population were not satisfied; the water that arrived was only used to a minimal extent to replace that which was used or lost on site. In fact, in addition to the low hydrographic relevance, one of the major problems of Cyprus is the poor water education of the Cypriots, especially with regard to the correct use of pipes, ducts and aqueducts. Furthermore, it is important to point out that the water infrastructures of the island are not very modern and not properly maintained; therefore, water waste is a very widespread phenomenon that significantly worsens an already extremely complex situation. The desalination plants, which are not very efficient, have been of little use, given that both in the southern and northern parts many Cypriots have experienced over time a notable presence of salt in the water that affects its correct use for domestic and productive purposes. This situation is due mostly to the presence of poorly performing desalination plants, insufficient in number and technologically obsolete which, in addition to not guaranteeing correct desalination of the water, have a decidedly negative impact on the environment. According to experts, Cyprus provides about 70% of its drinking water needs with desalination plants. However, these often use old reverse osmosis techniques that are energy-intensive and have significant impacts on the environment. Due to energy consumption, these desalination plants together emitted the equivalent of about 169 kilo-tons of CO2 into the atmosphere in 2018, or about 2% of the island's total greenhouse gas emissions [2].

Therefore, neither tankers nor desalination plants have contributed to mitigating the Cypriot water crisis. In recent years, among the strategies devised to resolve the issue, the construction of a large pipeline capable of connecting the island with Turkey has been taken into consideration. The main sponsor of this idea is Ankara itself, which has shown itself willing to build the infrastructure necessary to transport water from its territory to the TRNC, where Turkish influence is historically much more significant than in the southern part.

The Peace Pipeline: feasibility and details of the project

The construction of this ambitious project, not by chance called “The project of the century” [3], actually began in 1999 following a feasibility report presented to the Turkish Cypriot authorities. According to Ankara’s plans, the large pipeline would have had as its starting point the town of Anamur, located in the Mersin district, and as its arrival point the city of Kyrenia, considered the tourist capital of the TRNC.

Fig. 1: Veduta aerea del distretto di Mersin e Cipro

Fig. 2: La tubatura secondo i piani di sviluppo turchi

The cost of the operation, estimated at around 450 million dollars, was entirely borne by Turkey. About 80 kilometers long, the large pipeline lies on the bottom of the Mediterranean at a depth of 250 meters and supplies Cyprus with around 75 million cubic meters of water per day. This is the first project designed and built with the aim of bringing fresh water from one country to another in modern history; according to Turkish analysts, thanks to this infrastructure Cyprus will be able to count on abundant water resources for at least thirty years, or when the first maintenance works will have to be carried out [4]. After completing the necessary diplomatic procedures, the construction of the so-called Peace Pipeline began in March 2011. A few years later, in 2015, the project was completed amidst the satisfaction of the Turkish authorities and the skepticism of many environmental associations.

In a celebratory speech held a few weeks after the inauguration, Recep Tayyip Erdogan enthusiastically praised Turkey’s financial efforts and Ankara’s great engineering capacity following the actual construction of the Turkish-Cypriot Peace Pipeline. In a propaganda burst, the Turkish president stated that the purpose of this project is to guarantee water supplies for the entire island and not just for the northern part where Ankara’s influence is predominant. According to Erdogan, the humanitarian purpose of the large pipeline, also symbolized by the name of the project, was the main motivation that pushed the Turkish government to build this infrastructure. In reality, according to many analysts, the aqueduct would be an obvious attempt to increase Ankara’s influence on Cyprus by extending it to the southern part of the island, where the Greek majority and membership in the European Union have historically made Turkish penetration into Nicosia’s jurisdiction difficult. As Rebecca Bryant noted, the Turkish infrastructure, which will undoubtedly bring benefits to many Cypriots, has a clear matrix of geopolitical control over the island, considered by Ankara as its own appendix in the Eastern Mediterranean [5]. This is due to the Ottoman domination that characterized Cyprus for more than three centuries, that is from 1573 to 1876, when following the Conference of Constantinople (held in December 1876) the British Empire obtained the management of the island at the expense of the Sublime Porte [6].

Nowadays, despite obvious financial problems, Turkey seems to adopt an assertive foreign policy, devoted to the so-called “Neo-Ottomanism”. Ankara’s activism in various scenarios is there for all to see: from Syria to Libya, up to the Horn of Africa where in recent years Turkey has woven fruitful relations with Djibouti and Mogadishu [7]. In this scenario of great geopolitical dynamism, Cyprus fits fully into Erdogan's strategy aimed at the return of a strong Turkish influence both in the Mediterranean and in Africa. The construction of the large water pipeline therefore has the main purpose of linking the two segments of the island ever more closely to Ankara. Following the construction of the Peace Pipeline, the Cypriot water supply depends almost entirely on Turkey, making it extremely influential not only on an energy level but also in a political and strategic key in the affairs of the former Ottoman possession. In some respects, the investment of 450 million euros by a country that is not counted among the most financially significant nations in the world, should make us reflect on how important the Turks consider maintaining their influence in the Eastern Mediterranean. By virtue of this, it is not wrong to consider Ankara's move as a form of water colonialism.

Opposition to the Peace Pipeline

Reactions to the Turkish project have been very strong, both from the Greek Cypriots, understandably, and from the northern group that does not like excessive interference from Ankara in its affairs. In fact, apart from the political journalist Yiorgos Kakouris, who expressed himself positively on the Turkish investment in Cyprus [8], many environmental associations, political figures and ordinary citizens have strongly criticized the Peace Pipeline. The Association of Cypriot Biologists, based in Nicosia, has stigmatized the infrastructure considering it as the “mistake of the century”, in clear contrast to what the Turks had declared when presenting the project. According to them, the pipeline will only bring a minimal increase in Cypriot water resources. This is especially true in the summer months, when the combined effect of the heat and the massive presence of tourists will contribute heavily to reducing the available water also following the construction of the water pipeline.

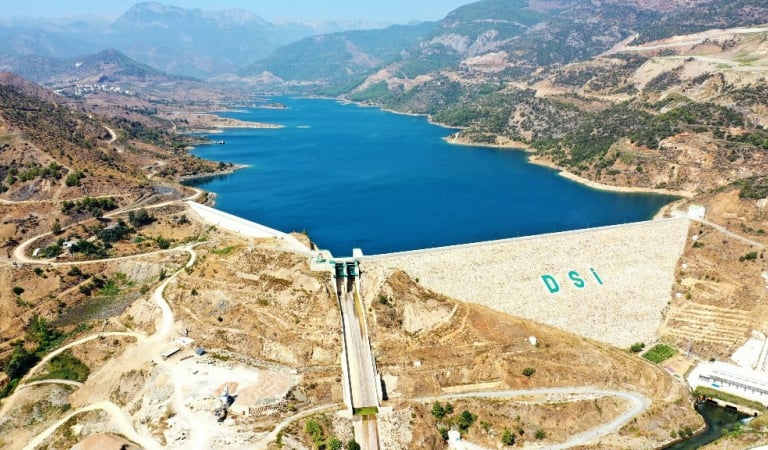

According to the Association, instead of focusing on the construction of a large infrastructure, it would be more appropriate to proceed with the promotion of policies that favor a correct environmental education of the Cypriots, in such a way as to minimize water waste. In addition, according to a group of Turkish Cypriot biologists, the pipeline would have serious negative environmental implications. Both in the Turkish town of Anamur, where the gas pipeline starts, and in the territory of the TRNC, the territory has been significantly and permanently altered. Entire communities and villages have been uprooted and relocated to other places to make room for the large infrastructure. On the Turkish side, in particular, much criticism has been raised in view of the construction of the Alaköprü dam, essential to create the artificial basin from which to draw water directed to Cyprus.

Fig. 3: Visione aerea di Anamur

Fig. 4: Diga di Alaköprü

According to Dursun Yildiz, director of the Hydropolitics Academy Association, only a small part (8%) of the water stored in the reservoir will be diverted through the pipeline. However, the medium- and long-term effects throughout the Mersin district remain unknown. According to some WWF reports presented between 2012 and 2013 specifically regarding the Alaköprü dam, the reduction of the water flow downstream of the structure could lead to significant environmental problems. Specifically, the lack of water resources following the construction of the project could harm the migration and spawning of fish and dry up the aquifers, which are responsible for the water sustenance of thousands of Turkish citizens living in the Mersin district [9].

Even on the political front, there has been no shortage of harsh criticism of the Peace Pipeline. On the part of Nicosia, quite predictably, the construction of the large Turkish infrastructure has raised many doubts. First of all, Greek Cypriots fear that Ankara’s presence on the island will increase exponentially, especially in a key sector such as water supply. According to the Greek Cypriots, the construction of the aqueduct will further increase and cement Turkish occupation in the northern part of the island. Nicosia played no role in the political process that led to the project; essentially, it suffered the strategic decisions taken in Ankara without being able to influence anything. Furthermore, with the aqueduct having its end point in the northern part of the island, Greek Cypriots are convinced that the real estate value of houses located in the TRNC will increase at the expense of properties in the south. This would compromise not only the governmental relations between the two groups, which are already quite tense, but also from a private point of view, since many individual citizens would find themselves with a lower real estate value in terms of value. In this way, a severe blow would be dealt to the Cypriot social peace, which would be shaken to its foundations. The southern part would suffer great inconveniences in terms of tourist arrivals, which have already decreased, while in the northern part, where the abundant presence of water guarantees a better welcome, arrivals have increased.

The Peace Pipeline has also raised serious concerns on the Turkish Cypriot front. First of all, according to Kibris Postasi [10], a Turkish-language newspaper on the island, the companies involved in the construction of the project were entirely Turkish, effectively excluding those already present on Cypriot territory. This has economically excluded many Turkish Cypriot workers who could have benefited from the construction operations which, as seen above, lasted approximately 4 years, from 2011 to 2015. Since it is an island where employment is mainly linked to the tourism sector in the warm seasons, having the possibility of working for 4 years even in the winter would certainly have benefited hundreds of citizens. Furthermore, the Turkish Cypriots are aware of the fact that the water coming from the Mersin district belongs to Turkey. In fact, Ankara exercises a very significant control function on the management of water resources and leaves little room for the local government. For example, the TRNC would prefer that the Kyrenia municipality manage the pipeline; the Turks, on the contrary, contract the management of the pipeline to a private company (obviously Turkish), which carries out its functions with a clear corporate intent, that is, it effectively sells the water to the highest bidder. Therefore, the initial humanitarian intentions have found few outlets once the project has been completed. In addition to all this, Ankara's influence in the internal affairs of the Turkish Republic of Northern Cyprus has increased dramatically following the construction of the aqueduct, leaving little room for manoeuvre for local politics. The Turkish Cypriots, who would be the main beneficiaries of the water coming from Anamur, are increasingly marginalised in the political decision-making processes. This is evidenced by a statement made on 25 October 2015 by Ekfan Ala, former Turkish Interior Minister. In a rally held in Bursa, the politician declared: "Cyprus is indebted to us"[11]. In essence, following the construction of the pipeline, the Turks feel indebted to the TRNC, and are improperly exercising greater influence than they did a few years ago.

Conclusion

As analyzed in this paper, Cyprus has a real problem related to water supply. The solutions that have been proposed over time have not had lasting effects, effectively leaving thousands of Cypriots in serious difficulty, especially during the summer months. Neither tankers nor desalination plants have helped to improve the situation. The questions that should be asked at this point are the following: can the aqueduct built by Turkey be a solution? What are Ankara's real intentions in this matter?

The answer to the first question is yes, with some reservations. In fact, the water flow from the aqueduct could theoretically and net of the still very large wastes, guarantee a certain autonomy to the island in terms of water. However, the lack of environmental education in Cyprus, especially with regard to the protection of scarce water resources, is a fact that must be taken into serious consideration. This situation is greatly exacerbated during the summer months, when the island fills up with tourists; during that period water is certainly not used sparingly, in fact it is used much more than it should be, given the scarce resources that Cyprus has. Therefore, as suggested by both the Association of Cypriot Biologists and Turkish Cypriot experts, a decisive change of pace regarding the correct use of water for domestic use would be desirable. Obviously, the construction of a large aqueduct capable of transporting tens of millions of cubic meters of water per day can make a difference and support thousands of citizens in combating recurring water crises. Nonetheless, if the habits of Cypriots do not change, it is very likely that other problems related to water scarcity may recur within a few years.

This last aspect allows us to answer the second question. Turkey, evidently, does not seem to have humanitarian purposes towards Cyprus, despite Erdogan's emphatic proclamations, since Ankara's objective is rather to increase its presence on the Mediterranean island. Due to the economic problems it has long suffered, Turkey is not able to exert financial pressure. Even from a military point of view, the issue would be extremely complex, given that the southern part of Cyprus is part of the European Union. Furthermore, even at a cultural level there is little room for maneuver; Greek culture is predominant on the island. Therefore, the construction of the Peace Pipeline, with the consequent attempt at water colonization, seems to be the only effective means to preserve and even increase Ankara's geopolitical role in Cyprus. At the moment, however, the somewhat "colonialist" management of the aqueduct is alienating the Turks from the initial consensus received in the months immediately following its construction. Indeed, as analyzed in this paper, even the Turkish Cypriots themselves, who share Ankara's culture and language as well as being the main beneficiaries of water resources, are skeptical about Turkey's real intentions.

_______________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________

[1] L’unico Stato a riconoscere ufficialmente Kuzey Kıbrıs Türk Cumhuriyeti, ovvero la Repubblica Turca di Cipro del Nord (RTCN) è la Turchia. Ankara ha iniziato ad intrattenere rapporti ufficiali con la parte settentrionale dell’isola a partire dal 1983, quando lo storico leader Rauf Denktaş, cipriota di origini turche, ne ha autoproclamato l’indipendenza.

[2] https://greenreport.it/news/acqua/acqua-potabile-piu-ecocompatibile-per-cipro/.

[3] Per dettagli maggiori sulla questione si rimanda a Pinar Tremblay, Turkey’s peace pipe to Cyprus, in «Al Monitor», ottobre 2015. https://www.al-monitor.com/originals/2015/10/turkey-cyprus-water-pipeline-delivers-fears.html.

[4] Ivi.

[5] Rebecca Bryant, Cyprus ‘peace water’ project: how it could affect Greek-Turkish relations on the island, in «EUROPP-European Politics and Policy», Ottobre 2015. https://blogs.lse.ac.uk/europpblog/2015/10/28/how-turkeys-peace-water-project-could-affect-relations-between-greek-and-turkish-cypriots/.

[6] In seguito all’inaugurazione del Canale di Suez, verificatasi nel 1869, l’Impero britannico aveva individuato in Cipro la base nel Mediterraneo orientale su cui puntare per controllare le nuove rotte che si sarebbero aperte. Approfittando della disfatta ottomana nella guerra russo-turca (aprile 1877-marzo 1878), i Britannici ottennero la gestione dell’Isola da un Impero Ottomano ormai debilitato ed in avanzata fase calante.

[7] Per ulteriori dettagli si rimanda a Chiara Gentili, La Turchia e il Corno d’Africa: strategie di penetrazione, in «Osservatorio sulla Sicurezza Internazionale», marzo 2021. https://sicurezzainternazionale.luiss.it/2021/03/29/la-turchia-corno-dafrica-strategie-penetrazion.

[8] Consapevole della difficoltà in cui versa l’isola da un punto di vista idrico, il giornalista ha più volte dichiarato che non è importante da dove proviene l’acqua o chi la fornisca. Per Yiorgos Kakouris ciò che conta è Cipro possa contare su risorse idriche certe e durature nel tempo. Cfr. Pinar Tremblay, op. cit., 2015.

[9] Ivi.

[10]https://www.kibrispostasi.com/c35-KIBRIS_HABERLERI/n58689-tcden-kktcye-su-getirilmesi-protokolunde-gorulmemis-muafiyetle.

[11] https://www.al-monitor.com/originals/2015/10/turkey-cyprus-water-pipeline-delivers-fears.html.

Abaqua

Via Cassia, 615

00189 Roma (RM)

© 2024. All rights reserved.

Codice Fiscale: 96584590580