Cape Town Water Crisis (2018): A Lesson We Should Never Forget

Filippo Verre - November 12, 2021

* L’immagine di copertina di questo paper è stata presa dal sito di Burn Media, nella sezione Meme Burn, consultabile al seguente link: https://memeburn.com/2018/01/cape-town-dams-theewaterskloof/

During the first half of 2018, Cape Town experienced enormous water supply problems. The economic capital and third largest city in South Africa risked experiencing a nightmare situation between February and April 2018: a total lack of water for both production activities and the population’s primary needs. In those months, the situation was truly desperate; “Day Zero”, the date when the water was expected to run out, had been set for April 22. Disturbances of all kinds with dramatic scenarios characterized the large South African metropolis for several weeks. Fortunately, after a peak of generalized despair that occurred during the last days of March, the serious water crisis subsided and the worst was averted. A series of spring rainfalls that hit Cape Town made it possible to overcome a truly tragic scenario. However, despite the happy ending, what characterized the economic capital of South Africa in those months deserves to be studied carefully to understand what went wrong and to prevent other crises of this magnitude.

Fig. 1 Visione aerea di Città del Capo

https://www.pinterest.it/pin/533113674643608287/

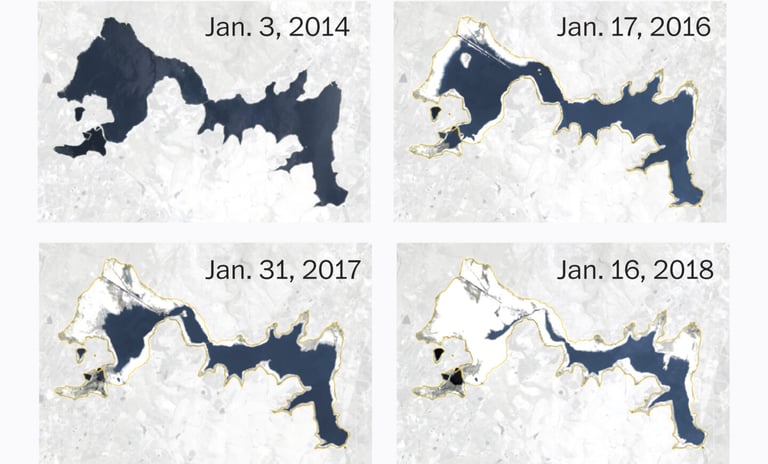

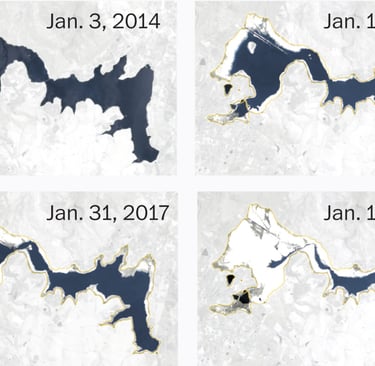

First, some data. Cape Town is a large urban agglomeration of about four million inhabitants that has experienced a powerful demographic growth in recent years. Since the mid-nineties (2.4 million inhabitants) the population of this metropolis has increased exponentially. Following this increase, there has not been a parallel growth of the city's water infrastructure, which has remained substantially the same with slight improvements. This situation is well illustrated by the numbers. In fact, if from 1995 to today the population of the city has grown by 79%, the city authorities and the South African government together have made modest changes to the water network, which in fact has only been expanded by 15% (1). To these basic circumstances must be added the serious lack of rainfall that had characterized the entire area for about three years. The years between 2016 and 2018 were the driest in the country since 1933, or since humidity was recorded in South Africa. To get a clear idea of how much the lack of rainfall influenced the water crisis that hit Cape Town, consider that from 1,100 millimeters of annual rainfall in 2013, in 2017 it had reached only 500 millimeters, or less than half (2).

The 2018 crisis was also favored by other factors indirectly connected to the lack of modernization of water infrastructure and low rainfall. From a political-administrative point of view, for example, it is believed that the situation was not managed in the best way. According to South African law, it is the central government's responsibility to finance and restructure public works, while local administrations are responsible for ensuring their correct functioning and use by individual citizens. This organizational dichotomy is not very functional for the effective management of the res publica, especially in times of crisis when decisions must be taken with a certain speed. If, as happened in the South African case, the national and local administrations belong to different political parties, the situation can become unsustainable, at times dangerous. In this regard, the delays in managing the water crisis also depended on the fact that the Democratic Alliance (AD), a political organization in opposition to the governing party (African National Congress, ANC), has administered the city since 2006 and the province since 2009. This could inevitably have complicated the collaboration between the city authorities and the central state. The fact that the water system was not managed by the local authorities but by the national ones, which in the 1990s asked for and obtained the administration of the dams and the aqueduct, seems to have negatively affected the quality of the measures adopted to deal with the crisis.

Fig. 2: Residenti di Città del Capo alle prese con la crisi idrica del 2018

Cape Town's water network and the measures taken to avert the crisis

The water network is mainly composed of six large dams located in the mountainous area of the city. In theory, they should be able to meet the fresh water needs of over four million inhabitants. As is known, the dams fill with water mainly in winter, from May to August, emptying more in summer, between December and February. The most important water infrastructure is undoubtedly the Theewaterskloof dam; built in 1978 and inaugurated in 1980, it has a capacity of 480 million cubic meters of water, approximately 41% of the water storage capacity available in Cape Town.

Fig. 3: La diga di Theewaterskloof a capacità piena

(ottobre 2013)

https://www.sapeople.com/2020/09/26/watch-theewaterskloof-dam-overflows-first-time-in-a-decade/

Fig. 4: La diga di Theewaterskloof durante la crisi idrica (marzo 2018) https://www.rainharvest.co.za/2019/04/jojo-tanks-suppliers/

As mentioned above, the dry climate and almost total absence of rainfall that characterized the three-year period 2016-2018 stressed the not very modern water infrastructure of the South African metropolis. To get an idea of the desperate situation that occurred in the spring of 2018, just compare Fig. 3 and Fig. 4.

To be fair, the city authorities desperately tried to remedy the difficult situation by adopting very drastic measures to avoid the so-called "Day Zero". It should be noted that, in some respects, the inhabitants of Cape Town did their part by suffering great inconveniences to the limits of endurance. According to a British study, water consumption dropped significantly within three years. The annual consumption of 1.2 billion liters went to 500 million liters at the beginning of 2018, when the estimated water capacity of the city dams had fallen below the worrying threshold of 13.5% (3). The containment measures imposed by Mayor Patricia de Lille, in office from June 1, 2011 to October 31, 2018, hit commercial activities first. Restaurants adapted to the lack of water by using it both less than before and by using (disposable) plates, while hairdressers for several months offered discounts to customers who washed their hair at home. Event organizers, from sports competitions to conferences, equipped themselves to bring their own bottles of water. Some activities were also suspended; for example, with several ordinances the mayor prohibited filling swimming pools, washing cars and sidewalks, watering gardens and sports fields.

Agriculture was undoubtedly the sector that suffered the most serious consequences of the restrictive measures. Farmers were forced to reduce water consumption by 40%, and in many cases to rely on private water reserves. As a result, production fell by about a fifth, with the unfortunate result of the loss of thousands of jobs not only in the city countryside but also throughout the province. In fact, half of the agricultural products exported from South Africa come from the Cape Town district. These are mainly crops that use a lot of water, such as citrus fruits and grapes.

Despite these drastic measures, which did not directly affect the individual well-being of the inhabitants of Cape Town but, extensively, affected the consumerist-recreational and agricultural sphere, the situation only got worse, aided by the lack of rain. At that point, given the gravity of the situation, it was decided to intervene on an individual level as well. The municipal authorities established an individual limit of 50 liters of water consumed per day, compared to the world average of 185 liters. It was an extremely severe measure that sparked protests and urban guerrilla warfare in various parts of the metropolis for weeks. Between February and March 2018, it was not uncommon to come across gangs of desperate people looking for sources from which to drink or take water for domestic purposes.

Fig. 5: Cittadini in fila per il quotidiano approvvigionamento idrico

https://www.ft.com/content/8a438352-fc76-11e7-a492-2c9be7f3120a

Fig. 6: Riduzione delle risorse idriche di Città del Capo 2014-2018

https://www.washingtonpost.com/graphics/2018/world/capetown-water-shortage/

This difficult situation was also exacerbated by the intrinsic characteristics of Cape Town, where the signs of apartheid are still evident today. The South African metropolis is in fact still profoundly unequal from a socioeconomic point of view. Its central and wealthy neighborhoods, inhabited mainly by whites, are contrasted with the poor and degraded suburbs, inhabited by blacks. This meant that impositions on the individual sphere to deal with the crisis, such as the limitation of 60-second showers or moderation in the use of toilets and laundry, were received with a certain annoyance in the wealthy and white areas of the city. In many cases, the richest inhabitants equipped themselves with private tanks to store water, not contributing in fact to the water saving hoped for by the mayor Patricia de Lille. Furthermore, in the poor neighborhoods, there were riots against the authorities who had imposed restrictions in areas already subject to water supply difficulties. In short, the multi-ethnic and still classist composition that characterizes Cape Town certainly did not have a positive influence on the management of the crisis.

Overcoming the crisis: a lesson for the world

Although the situation continued to worsen both in public and private terms, Cape Town never experienced the much-feared “Day Zero”. A series of heavy spring rainfall, combined with the energy saving policies that the city authorities had adopted for months, averted the worst. As time passed, the watersheds filled up again and the city’s population was gradually able to return to living a normal life. It took months, however, before the situation returned to normal; throughout 2018, in fact, the South African metropolis remained in a state of constant observation. Even today, precisely because of those chaotic and in some ways terrible months, Cape Town bears the signs of what happened. The agricultural sector, which in the meantime had lost around 30,000 jobs both in the city and in the province, has not fully recovered (4). Especially in the poorest neighborhoods, a basin from which many South African agricultural entrepreneurs used to find low-cost labor, there are still gangs of strays who were previously employed in the countryside around the city. In the richest neighborhoods, moreover, it is very common to still find numerous cisterns outside houses, three years after the crisis. These cisterns are now, so to speak, part of the architectural component of entire areas of the city.

There are many reasons why not only those in the field but also the public and international organizations should consider the events in Cape Town with the utmost attention. First of all, the fact that a water crisis of this magnitude occurred precisely in South Africa, which is certainly a “more structured” country than others on the continental scene, should give us pause for thought. On an economic level, South Africa is an extremely important country; is a stable member of the G20, of the BRICS and has a gross domestic product of around 330 billion dollars per year. This is certainly no small thing, especially if we also refer to the per capita GDP of South Africa, which amounts to 5,400 dollars. Compared to the average per capita GDP of Africa, which amounts to 1,900 dollars, we can see that the South African economic situation is significantly positive (5). In addition, it is an industrialized nation that has invested heavily in large renewable energy production plants for years. Four of the ten most important solar and photovoltaic energy plants in Africa are present, or are being built, in South Africa. Despite all this, the government based in Pretoria and the municipal authorities of Cape Town were not able to prevent in time the water crisis that had been looming since 2016, when rainfall had started to become scarce and the levels of the city's river basins had started to drop. This is because water supply is a very complex issue that requires coordination, planning and punctuality in the measures to be adopted.

The South African case has been very useful in some ways, as it has allowed us to test how a large-scale water crisis can upset the life of a metropolis. In fact, it was the first large city that found itself having to manage the threat of a total shutdown of the taps due to lack of water. It is therefore a case that will set a precedent. There are many lessons learned from the Cape Town affair. First of all, according to Neil Armitage, a university professor of "hydraulic constructions" in Cape Town, following the events of 2018 we are off.

________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________

1 https://www.rinnovabili.it/ambiente/crisi-idrica-citta-del-capo/

2 https://www.ilpost.it/2018/05/06/siccita-citta-del-capo/

5 Non è questa la sede opportuna per entrare maggiormente nel dettaglio della situazione economica sudafricana ma si tenga presente che, a fronte di dati tutto sommato positivi, il Sudafrica sperimenta ancora oggi una forte diseguaglianza economico-sociale. La ricchezza è detenuta in larga parte dalla popolazione bianca (10%), che dispone di circa del 60% del totale.

Abaqua

Via Cassia, 615

00189 Roma (RM)

© 2024. All rights reserved.

Codice Fiscale: 96584590580