The “Water War” Between Russia and Ukraine: The Case of the North Crimean Canal

Filippo Verre - August 8, 2022

* L’immagine di copertina di questo paper è stata presa dal sito Kyivpost, consultabile al seguente link: https://www.kyivpost.com/article/content/war-against-ukraine/north-crimean-canal-supplied-with-water-from-two-reservoirs-348206.html

Over the past few months, numerous dossiers, reports and in-depth analyses of various kinds have been produced – both in Italy and around the world – with the specific aim of understanding the reasons that pushed Moscow to invade Ukraine. Strategic factors of various kinds, ideological, political and economic motivations have been taken into consideration, in addition to recalling in detail the peculiar relationship between Ukraine and Russia, which has been very close for centuries. Surprisingly, little or nothing has been written on a decidedly primary issue that has greatly contributed to worsening a relationship – that between Kiev and Moscow – that has already been very precarious since 2014: the water factor. Yes, water, or rather the control of water, has played a decisive role in the relations between the two contenders. In fact, especially with regard to the southern front, Russia attacked the territory under Ukrainian control precisely to guarantee Crimea, a peninsula de facto under Moscow's control since February 2014, the water supply necessary to provide sustenance to the approximately two million Crimean residents. Following the construction of a dam by the Ukrainian authorities in 2014 in the Kherson oblast, not far from the border with Crimea, the peninsula under Russian control had suffered a sharp cut in water supplies, largely ensured by an artificial canal: the North Crimean Canal. Among the various reasons that pushed Russia to attack Ukraine, therefore, there is also a water motivation.

North Crimean Canal: data and strategic importance

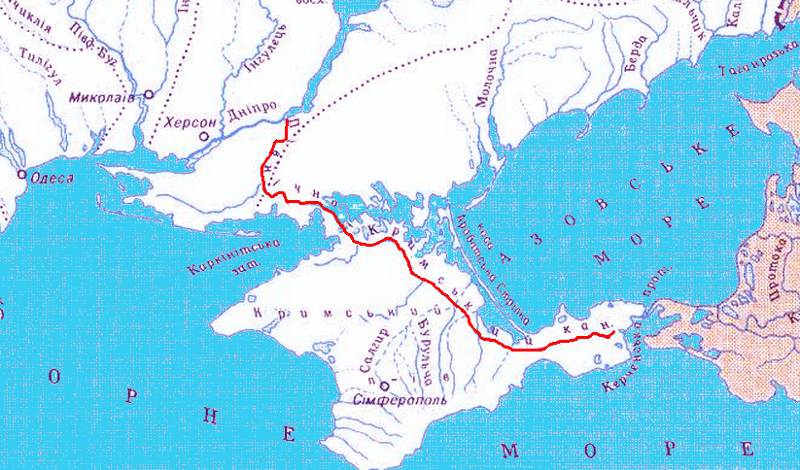

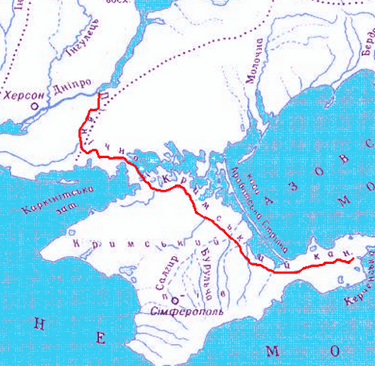

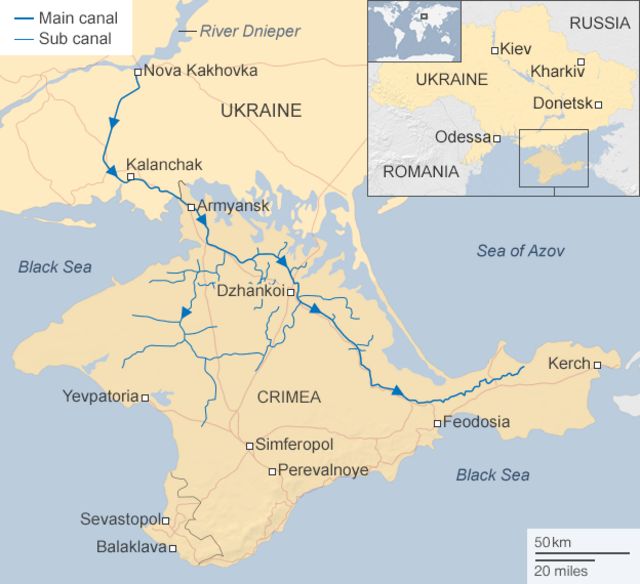

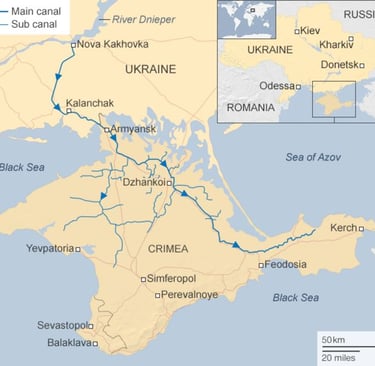

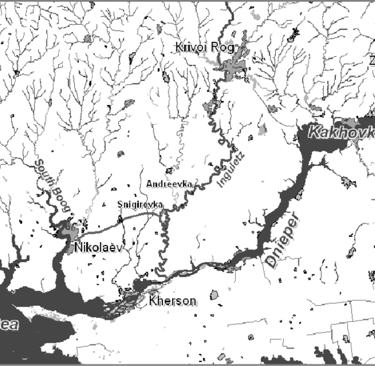

The North Crimean Canal (NCC) is an extremely strategic hydraulic structure for the water supply of Crimea. The latter has a fairly arid territory, where there are no natural watercourses of great importance capable of irrigating the countryside of the peninsula with the precious liquid. Built in the Soviet era between 1961 and 1975, the NCC has contributed greatly to making Crimea – especially the eastern part – a green place rich in crops of various types[1]. The 402 km long canal originates in the city of Tavriysk (Ukraine), where it draws from several large reservoirs fed by the Dnieper River. This is one of the most important waterways in Europe both in terms of length and flow. In fact, with over 2,200 km, the Dnieper is the fourth longest river on the continent – after the Volga, the Danube and the Ural – and has a truly considerable drainage basin, as much as 516,000 km². This data places the Dnieper in third place in Europe in terms of size, after the Volga and the Danube[2]. The NCC extends in a south-east direction before ending its artificial course in the small village of Zelnyi Yar in the Lenino District of Crimea. From there, an aqueduct carries the water to the city of Kerch, at the eastern end of the peninsula.

Fig. 1: Il North Crimean Canal lungo tutto il suo corso

https://www.bbc.com/news/world-europe-27155885

As shown in Fig. 1, the starting point of the NCC is located in the southern reaches of the Kakhovka reservoir. The reservoir covers a total area of 2,155 km² in the Ukrainian oblasts of Kherson, Zaporizhzhia and Dnipropetrovsk, which became infamous due to the well-known war events. The Kakhovka reservoir is 240 km long and about 23 km wide at its widest point. The depth varies from 3 to 26 meters, with an average of 8.4 meters and a total water volume of 18.2 cubic km.

Fig. 2: Mappa della riserva di Kakhovka

https://www.researchgate.net/figure/The-map-of-the-Kakhovka-Reservoir-and-Lower-Dnieper_fig1_232274430

Before the Russian annexation in February 2014, the NCC satisfied over 85% of Crimea’s water needs. In retaliation, the Ukrainian authorities decided to adopt a series of strategies to substantially cut the water flow that was ensured through the canal. Among the various proposals, we note the aforementioned (semi-secret) project that envisaged the construction of a “blocking” dam of the entire canal south of Kalanchak, about 16 km north of the border with Crimea. And in fact, the water and environmental damage that occurred on the peninsula following the construction of the dam in the Kherson Oblast was truly significant. Consider, in fact, that over the decades the Crimean peninsula had become a real open-air garden thanks to the abundant water resources coming from the canal. To get an idea of this, consider that in the early 1980s the Soviet authorities decided to introduce rice cultivation in Crimea, a food that requires large quantities of water to obtain good production. Several tens of thousands of people moved to Crimea between the late 1970s and early 1990s, attracted by the mild climate, high levels of employment in the agricultural sector and a general well-being favored by the abundant presence of water.

Since 2014, or when the Kiev government effectively interrupted the flow towards the valley, Crimea has suffered a series of serious water and food crises. Despite Russia's huge economic and material effort to deal with the hardships suffered by the population, the situation has not improved much. Since 2017, Russian authorities, in coordination with the local government of Crimea, have built small hydroelectric power plants, new wells, diverted local water sources, built a bridge from Russia to the peninsula for the transport of food and goods, and reoriented agriculture towards the cultivation of products that require less water consumption. However, food and electricity problems due to water stress have only been solved temporarily. This is because, as mentioned, the peninsula is in fact almost entirely dependent on the water transported through the NCC. Production activities have also been greatly affected by the reduced water resources. In this regard, the case of Crimean Titan, the largest titanium dioxide producer in Europe based on the peninsula, which has seen its production drastically reduced between 2014 and 2021 is noteworthy[3].

According to several analyses[4], the reduction in water flow has caused a massive shrinkage of the cultivated area in Crimea, which has gone from 130,000 hectares in 2013 to just 14,000 in 2017. The canals that Crimean authorities relied on for agricultural and industrial activities soon became sad and desolate dry arteries, unable to provide any water benefits to many communities. As a result, even the small and medium-sized water basins built over time in Crimea have suffered worrying cases of evaporation, further aggravating the environmental and energy crisis that has been present on the peninsula almost continuously since 2014. The negative peak occurred in the summer of 2021, since, in addition to the lack of water for irrigation purposes, Crimean residents had to ration the precious liquid for many hours a day even for basic needs. In July 2021, specifically, widespread water shortages meant that public aqueducts could only be used for three to five hours a day.

The Russian reaction: from international protests to a full-blown “water war”

According to a 2015 study[5], 72% of the water coming from the NCC was intended for agriculture, 10% for industrial activities, while the aqueduct and other public uses constituted 18%. These data once again demonstrate the extreme importance of the canal for Crimea, especially for production activities related to agricultural and industrial production. Essentially, control of the peninsula without being able to count on the water resources guaranteed by the flow coming from the NCC represented a worrying situation of strategic stalemate for the Kremlin. It is therefore not wrong to consider how, from a Russian perspective, the cut in water supplies by Kiev has in fact compromised the success of the entire “Crimea operation”. The lack of water, among other factors, has clearly weighed on the budget allocated by Moscow to manage the new territory "acquired" in February 2014. According to some analyses[6], the first five years of Russian occupation of Crimea have cost approximately 1.5 trillion rubles, equal to over 20 billion dollars. This is a real disproportion, to which must be added the lost revenues due to the substantial paralysis of the Crimean agricultural sector following the construction of the "dam". Furthermore, the deployment of numerous Russian soldiers in Crimea to prevent any military reactions by Kiev has weighed further on the already scarce water resources present in the region.

Initially, Moscow's reaction to the cutting of water supplies was inserted in a context of international law. In fact, there were numerous appeals (falling on deaf ears) that Russia made to various international courts with the aim of forcing Ukraine to loosen the blockade imposed on the Crimean peninsula. Expressions such as “attempted genocide of the Crimean people,” “ecocide,” and “malicious environmental crisis” have been repeatedly used by Russian diplomats to try to unblock a dangerous stalemate. The crux of the Russian position was one very specific issue: the blockade of the NCC was nothing more than a punishment for Crimea’s political decision to “reunite” with the motherland. Depriving the more than two million residents of Crimea of the water needed even for basic needs was tantamount to contravening various international laws, as well as blatantly violating human rights, which unequivocally establish access to water as a fundamental right. According to the Russians, Kiev never sought a compromise solution, such as negotiating the price of water or sharing the costs following the maintenance of the canal, but simply suppressed Crimea’s main source of supply.

In 2017, Russian dignitaries filed a complaint with the European Court of Human Rights (ECHR) against Ukraine. The governor of Crimea, Sergei Aksyonov, also indicated his intention to file a separate complaint seeking substantial compensation, claiming that Ukraine had used Crimea’s water dependence on Kiev’s infrastructure as a weapon, resulting in an “act of state terrorism.”[7] Aksyonov has openly criticized the international community for failing to intervene in support of Crimean residents, who were left to deal with several environmental crises related to water stress induced by Kiev’s actions.

Despite protests, the ECHR did not accept Russia’s position. In June 2020, Russian lawmakers turned to the United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights (OHCHR) with a similar strategy. Here too, in fact, Moscow complained that Ukraine had deprived “millions of people of the fundamental and inalienable right to drinking water”[8]. A few months later, on 14 September 2020, the Russian Human Rights Council (an advisory body to the Russian presidential administration) filed another complaint with the OHCHR, arguing that Ukraine’s actions “contravene the United Nations Convention on Transboundary Watercourses and International Lakes[9] and the Berlin Rules on Water Resources[10]. These are two important declarations that protect the right to drinking water and access to water supplies by all peoples and countries belonging to the international community.

As happened with the ECHR, the complaints filed with the OHCHR also did not have the effect hoped for by the Russians. Thus, Moscow filed a new complaint with another international body. In March 2021, the Kremlin’s envoy to the Organization for Security and Co-operation in Europe (OSCE) listed violations of the Convention on Human Rights and Fundamental Freedoms resulting – from a Russian perspective – from the closure of the North Crimean Canal. In its complaint, Russia argued that Ukraine’s actions violated the rights of Crimean residents under several articles:

Article 3 (prohibition of torture);

Article 8 (respect for private and family life);

Article 14 (prohibition of discrimination) of the Convention,

Article 1 of Protocol 1 (right to property);

Protocol 12 (general prohibition of discrimination).

Moscow’s calls to increase global attention on the issue of Crimea’s water supply have also been not lacking online. As can be seen from Fig. 3, in fact, even on social media (specifically, Twitter) the issue was addressed from the perspective of failure to respect human rights. This proves that the Kremlin's diplomatic strategy was entirely based on the alleged Ukrainian infringement of the fundamental right to access to water.

Fig. 3: Campagna di sensibilizzazione russa via social (Twitter) sulla questione del NCC, 14 agosto 2019

https://twitter.com/mfa_russia

From a legal perspective, the Russian appeals were almost certainly destined to fall on deaf ears. It is no coincidence, in fact, that all the courts to which Moscow appealed gave a negative outcome. This is because, in legal terms, the Russian claims were and remain very weak. The Crimean water issue, by law, does not concern law but international politics. Given that Crimea is internationally recognized as part of Ukraine illegally occupied by Russia, it is the law on territorial occupation – the so-called Fourth Geneva Convention – that clearly defines the obligations of the occupier, who is responsible for ensuring the well-being of the people living in that occupied territory. Therefore, the responsibility for ensuring that the population of Crimea has access to water lies exclusively with Russia as an unrecognized occupying state. Furthermore, even with regard to the complaint of violations of human rights, Moscow has feeble claims. Such a violation only applies if there is no water for basic human needs, such as washing, cooking or drinking. Not if the unavailable water is needed to provide the resources needed to manage large-scale agricultural production or rice cultivation.

In response to Moscow’s legal battle, Ukraine has not sat idly by. Kiev claims that the NCC was blocked because the new leadership in Crimea unilaterally stopped paying water bills after the peninsula became an integral part – de facto but not de jure – of Russia. Ukrainian authorities also claimed that the facility needed major maintenance before it could be reopened and that there was no attempt by Russia to work with them to repair the canal. Indeed, as soon as the peninsula came under Moscow’s control, the Kremlin replaced Ukrainian canal management personnel with Crimean and Russian technicians who had no contact with Kiev. This contributed to worsening a situation already made extremely complex by the abrupt passage of Crimea from Ukrainian to Russian administration.

Conclusion

The Crimean water issue undoubtedly played a significant role in the motivation that pushed the Russians to attack last February 24. After the failure of the legal strategy at various international forums and with an exorbitant economic outlay for the management of a Crimea without water, Moscow opted for war. A few hours after the invasion, Russian troops blew up the "dam" in the Kherson oblast, effectively restoring the flow downstream guaranteed by the NCC and irrigating the arid plains of the peninsula with the precious blue gold. Therefore, from a purely concrete perspective, the Kremlin's aggressive war strategy has unblocked a critical situation both for the local government of Crimea and for the image of good governance propagated by Moscow, seriously compromised following the Ukrainian countermove. However, it should be noted that the resolution of a water conflict through military measures is certainly not ideal. The water war between Russia and Ukraine – inexplicably little covered in the public debate and in the main national media – is a worrying attempt to resolve interstate environmental disputes through the use of violence.

There are many cases in which countries involved in tensions of various kinds manage at a technical level the water resources that they find themselves sharing against their will[11]. This is a joint management aimed, as much as possible, at exploiting the resource and maintaining peace. This model involves the creation of a local authority consisting of a small mixed committee made up of technical personnel from both countries. The committee, which has full legitimacy for management, meets regularly, makes decisions, delegates tasks and carries out measures with little or no reporting to higher authorities. In this way, politics remains outside the issue, preventing the emergence of tensions and encouraging relationships of trust between the members of the committee as they find themselves working in close contact. This cooperation model – conceived in the Soviet era – is still in use in the case of the Arpacay dam (between Armenia and Turkey) and the Stanca-Contesti dam (between Moldova and Romania), three decades after the dissolution of the USSR. In both these cases, local committees administer the regulation of the water flow with satisfactory results, without the issue being brought up to exacerbate political and diplomatic relations.

The tensions between Russia and Ukraine, which resulted in a real war of aggression by Moscow, have deep roots that go beyond the mere water issue, although of primary importance. That said, as analyzed in this paper, water, or rather the lack of water, has represented an element of serious tension for Russia and has undoubtedly contributed to exacerbating tempers. By virtue of this, it seems more necessary than ever for the Kremlin and the Kiev government to realize that water cannot and must not be used as an instrument of war. In light of the great hardship suffered by the Crimean population following the construction of the “dam barrier”, it would be desirable for the two warring nations to adopt a responsible approach to water management in Crimea. While Russia bears primary responsibility for unleashing a large-scale military attack, with the construction of the dam on the NCC, Ukraine has significantly exacerbated already very strong tensions with the Russians. It should also be noted that following the blocking of the water flow downstream, Kiev has condemned two million of its former citizens (de facto) to suffer from repeated cases of water stress, thus demonstrating an imprudent political realism.

The Crimean water crisis will be definitively resolved when the artificial canal built in the Soviet era is free and operational. To achieve this, it is necessary for the two contending countries to establish a memorandum of understanding in which the management of the infrastructure is delegated to local technicians animated by a spirit of cooperation.

___________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________

[1] D’altra parte, è noto che tutta la regione in questione è conosciuta per la fortissima produzione di cereali.

[2] Per avere un’idea dell’estensione del Dnepr si consideri che il Po, principale corso d’acqua presente sul suolo italiano, ha un bacino idrico di circa 71.000 km², ovvero oltre sette volte inferiore rispetto al grande fiume che nasce in Bielorussia e che attraversa tutto il territorio ucraino prima di sfociare nel Mar Nero.

[3] Per ulteriori dettagli sulla vicenda si rimanda a: https://www.ejiltalk.org/the-proceedings-flow-while-water-does-not-russias-claims-concerning-the-north-crimean-canal-in-strasbourg/.

[4] Per maggiori dettagli si rimanda all’opera, tra le altre, di V. A. Vasilenko, Hydro-economic problems of Crimea and their solutions, in «Geography of Resource Use Management», pp. 89-96, 15 marzo 2017.

[5] I. Izotov, The State Duma will consider a problem of ecocide of Crimea, in «Rossiiskaya Gazeta», 2015.

[6] https://www.newsecuritybeat.org/2022/03/hydropolitics-russian-ukrainian-conflict/.

[7] https://www.newsecuritybeat.org/2022/03/hydropolitics-russian-ukrainian-conflict/.

[8] https://www.ejiltalk.org/the-proceedings-flow-while-water-does-not-russias-claims-concerning-the-north-crimean-canal-in-strasbourg/.

[9] La Convenzione delle Nazioni Unite sui corsi d’acqua transfrontalieri e sui laghi internazionali è reperibile al seguente link: https://unece.org/DAM/env/water/pdf/watercon.pdf.

[10] La dichiarazione relativa alle Norme di Berlino sulle risorse idriche è reperibile al seguente link: http://www.cawater-info.net/library/eng/l/berlin_rules.pdf.

[11] A tale riguardo, ci siamo recentemente occupati dello spinoso caso della GERD etiope e delle relative tensioni internazionali.

Abaqua

Via Cassia, 615

00189 Roma (RM)

© 2024. All rights reserved.

Codice Fiscale: 96584590580