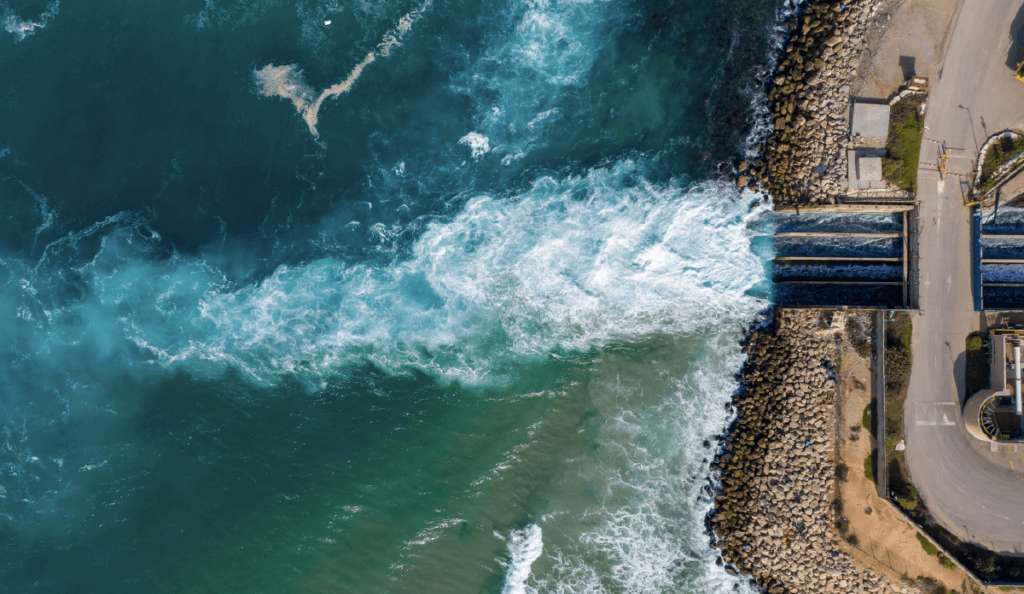

* L’immagine di copertina di questo report è stata presa dal sito Memodo Blog, consultabile al seguente link: https://blog.memodo.it/desalinizzazione-dellacqua-impianti-fotovoltaici/

For a long time, Italy was able to do without desalination as a means of producing water resources. There were various reasons for this. In addition to a traditional institutional and environmental refractoriness towards this ancient technique, the abundance of fresh water along our peninsula, in various forms, meant that the institutions could almost completely ignore desalination as a valid method of supply. Until a few years ago, the abundant precipitation and the large mass of snow that each winter settled on our Alps and along the entire Apennine range guaranteed the Belpaese an almost privileged condition from an environmental point of view. In fact, despite climate change having been a sad reality for some time now, with the related negative effects that we are all aware of, Italy until very recently had not experienced particular cases of environmental crisis, water stress, or difficulty in supplying water. The main reason for this was due to the fact that the numerous rivers and streams that flowed from our mountains throughout the peninsula were constantly supplied with precious glacial water. In addition, of course, to abundant, continuous and relatively predictable rainfall.

However, times change. In the last ten years, there have been three serious episodes of water stress. 2022, a true annus horribilis in terms of drought, has been consigned to history as the driest year of this millennium and one of the driest in recent European history. The damage caused by the drought, which began in May and ended with the beginning of the first autumn rains in late October, was devastating. According to Coldiretti's analyses, in that year Italy had a deficit of over 10% of national agri-food production and damage estimated at around 6 billion euros, in addition, of course, to the enormous inconvenience caused to private citizens and companies. As reported in a study of ours some time ago, the 2022 crisis was largely caused by the massive rainfall deficit that effectively prevented the glaciers, which have always been invaluable reservoirs of water for the Italian supply, from supplying the countless streams, creeks and waterways scattered across our national territory. The scarcity of precipitation, both rain and snow, is one of the main negative effects of climate change. In Italy, historically sheltered from rainfall deficit phenomena, recent cases of low rainfall in the winter seasons are laying the foundations for future water crises. From this perspective, based on the current climate and environmental situation, it is not a question of "if" but of "when" the next drought will occur.

Given this complicated situation, it is necessary to find new sources from which to supply ourselves in the highly probable event that a drought crisis occurs. The use of desalination seems to be a valid alternative both for the peninsular conformation of the country and above all given the modern production techniques that reduce the environmental risk due to pollution and emissions, as well as promoting a constant production of desalinated water without necessarily resorting to fossil fuels. In this report, after having schematically underlined with some data the damage that the rainfall deficit has caused to the environment and the Italian economy, we will highlight the radical institutional and bureaucratic change regarding the construction of desalination plants after the 2022 water crisis. In fact, we have moved from the Salvamare Law (Law No. 60 of 17 May 2022), which is highly restrictive towards desalination, to the “Drought” Decree-Law no. 39 of 14 April 2023, subsequently converted into law (N. 68 of 13 June 2023), in which desalination plants were in fact favoured by a significant de-bureaucratisation.

Altered precipitation and glacier erosion:

The main causes of Italian water stress Global warming is the great climate challenge of our time. According to almost all of the world's scientific literature, despite the measures adopted - especially in the West to be honest - global greenhouse gas emissions have not yet begun to decline and have well exceeded 50 billion tons per year. In the absence of a rapid reversal of the trend, by the end of this century the average global temperature will be at least 3 °C higher than in the pre-industrial period. This is an alarming fact from all points of view. Higher temperatures not only lead to a more rapid contraction of the water resources present in a territory but also to an alteration of both rain and snow precipitation. This is because heat significantly interferes with the water cycle, which is the mechanism by which nature generates precipitation. As reported in various studies published on ISPRA, a greater volume of water that evaporates in a short time due to global warming creates the conditions for hurricanes, storms, and "water bombs" that do nothing but worsen an already troubled environmental situation.

According to the latest analyzes by the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC), the alteration of precipitation caused by climate change has reduced water security with significant impacts also in terms of agriculture and food. In addition to the lack of rain, in recent years extreme weather events (floods, inundations, landslides) have intensified, also harbingers of instability and environmental degradation. From this study published by the United Nations, it is clear that almost half of the world's population is exposed to cases of severe water scarcity for at least part of the year, with possible flooding. It seems like an oxymoron but it is what unfortunately occurs in many areas of the world. For example, as reported in a paper of ours some time ago, in 2019 the Indian city of Chennai experienced a double water crisis in the space of a few months. After a severe drought that paralyzed the capital of Tamil Nadu for months, a severe flood resulting from a particularly powerful monsoon hit the parched soil of the metropolis, causing a double emergency, drought and flooding.

The ongoing global warming does not impact all regions of the world in the same way. For example, the Mediterranean basin area is classified as a climate hotspot, as it is more exposed to the effects of the environmental crisis. In Italy, specifically, the growth of temperatures is traveling at double the speed compared to the planet average. According to the report (2023) by Italy for Climate, today the average temperature of our country has increased by almost 3 °C compared to the pre-industrial period, compared to the +1.1 °C of the world average. Even assuming that we manage to cut emissions and contain global warming to no more than 2°C, as foreseen by the Paris Agreement, in the coming decades Italy could have to deal with an average temperature higher by as much as 5°C. This value could be much higher in some contexts, such as in large urban agglomerations or on islands, where water supply is already a challenge in itself.

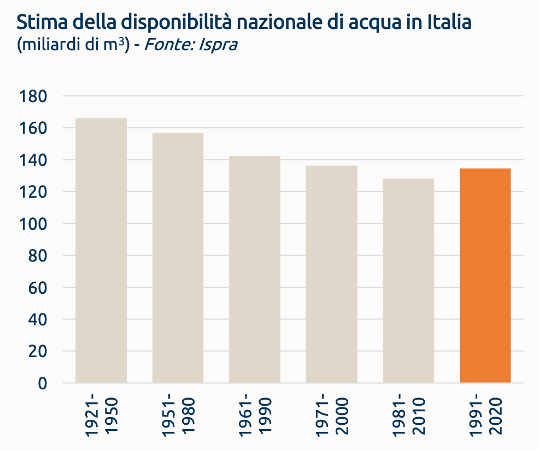

As mentioned, therefore, the increase in temperatures causes an alteration of precipitation, the main effect of which, in the short term, is the decrease in regular rain and snow. In this respect, from a statistical point of view, it is interesting to report the data extrapolated by ISPRA, which has reconstructed an extended historical series of the national water balance. Referring to the average of the thirty-year period 1991-2020 [1], the annual input of water on the national territory, given by the total precipitation, was 285 billion m³. Of this impressive figure, over half returned to the atmosphere through evapotranspiration [2]. The water that remains is the internal flow, composed of runoff and aquifer recharge. This is what is normally considered a renewable water resource. According to the statistical analyses of ISPRA, in the last thirty years the average availability of water resources in Italy has been equal to 134 billion m³ per year.

ISPRA’s analysis allows us to note that, in the European panorama, Italy enjoys a good availability of water resources. According to this Eurostat report on European water statistics, the average internal flow in Italy is the highest in Europe after France and Sweden, higher than both the German and Spanish ones. It should be noted that the flow depends on the size of a country; the larger a country is, the greater the rainfall intercepted. Nonetheless, even taking into account the availability of the resource in relation to the territory, Italy, with over 400,000 m³/km², is positioned above the European average and the values of France and Germany, slightly higher than 300,000 m³/km², and double the Spanish figure. Again according to Eurostat, looking at the availability per capita, due to the higher than average population density (about double that of France and Spain, for example), the Italian values are a little lower than the European average.

Fig. 1: Storico della disponibilità idrica italiana 1921-2020

https://italyforclimate.org/wp-content/uploads/Andrea-Barbabella-Italy-for-Climate-presentazione-Conferenza-nazionale.pdf

However, despite good water availability, in recent decades Italy has witnessed a progressive reduction in the average annual availability of renewable resources. In fact, we have gone from an average of 166 billion m³/year in the thirty-year period 1921-1950 to the 134 of 1991-2020 mentioned above, with a reduction of approximately 20%. According to the analysis of various bodies including ISPRA and EUROSTAT, this trend is destined to consolidate and worsen in the coming years due to climate change. Even imagining that global warming is limited to no more than 2°C by the end of the century, water availability at a national level would still be reduced by another 10%, bringing the annual figure to just over 120 billion m³/year. If, however, we fail to change pace on decarbonisation policies and the temperature remains at +3/4 °C, by the end of the century we could have a further 40% less of the resource, with a worrying projection of around 81 billion m³/year, rounded up. Naturally, this reduction would affect different areas of the country differently and in some areas of Southern Italy, already struggling from a water point of view, the availability of water could be reduced by even greater percentages, causing worrying supply crises in the short-long term.

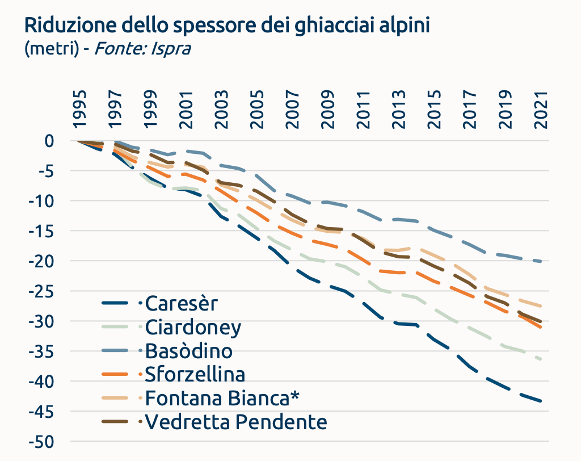

As mentioned at the beginning of this report, the areas most affected by the decrease in precipitation are the mountains. In this regard, according to the National Plan for Adaptation to Climate Change – PNACC, Alpine glaciers have already lost 30% to 40% of their volume. In just over twenty years, due to global warming, Alpine glaciers have lost over 50 km³ of water and have lowered by an average of 25 meters. This is an extremely alarming fact. In this regard, some time ago, in a report produced for the Mountain Partnership, we highlighted how the reduction of snow and the disappearance of glaciers can compromise the fundamental role of supplying these mountain ecosystems for the summer seasons. A lower contribution of glaciers in terms of water flow does nothing but increase the risk of water crises. As evocatively mentioned in the report published on Italy for Climate in relation to the lowering of the ice that has occurred in the last twenty years, it is as if a city of ice made up only of 8-story buildings and with a surface area of more than 2000 km², or twice that of Rome, the largest city in Europe, had disappeared.

Fig. 2: Erosione delle risorse idriche glaciali (1995-2021)

https://italyforclimate.org/wp-content/uploads/Andrea-Barbabella-Italy-for-Climate-presentazione-Conferenza-nazionale.pdf

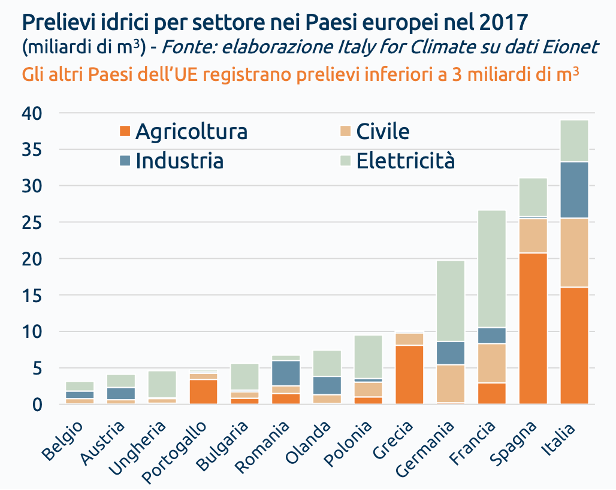

In addition to the decrease in water available on our national territory, it is appropriate to point out another pair of data that contribute to increasing Italian water stress. According to EUROSTAT, Italy is now the European country with the highest levels of total water withdrawals, primarily due to agriculture (but not only). With almost 40 billion m³ withdrawn annually, the Belpaese clearly detaches Spain, at just over 30 billion, followed by France, with almost 27, and Germany with an annual withdrawal of less than 20 billion m³. In addition to this, the very high losses in Italian water infrastructures are reported. According to this document by Rete Ambiente – Osservatorio Normativa Ambientale, the rate of losses in our aqueducts exceeds 42%. These two data – total water withdrawals and rate of loss in aqueducts – combined with the alteration of precipitation and the decrease in the water supply provided by glaciers, provide a clear idea of the great need on the part of Italy to find other sources of supply. In fact, both from an agricultural and industrial point of view, the probable water crises of the future will deal very heavy blows to the national economy and society.

Fig. 3: Prelievi idrici europei (2017)

https://italyforclimate.org/wp-content/uploads/Andrea-Barbabella-Italy-for-Climate-presentazione-Conferenza-nazionale.pdf

From the Salvamare Law (2022) to the Drought Decree Law (2023): the de-bureaucratization of Italian desalination

Before the 2022 water crisis, building a desalination plant for public utility purposes was not at all simple. Obtaining bureaucratic permits was very long and cumbersome. In addition to an Environmental Impact Assessment (EIA) that preceded the green light from the authorities, a series of very stringent guidelines provided by the Ministry of Health had to be respected. In fact, the desalination process was considered as a last resort, meaning it could only be taken into consideration when every other measure – improvement of water networks, efficiency, restructuring of plants, etc. – had already been implemented with poor results. Furthermore, from a sustainability perspective, the production of brine as an industrial waste from the desalination process was of great concern given the high disposal costs and environmental toxicity. In this regard, in fact, it is worth noting that, if reintroduced into marine environments, brine causes very serious damage to aquatic flora and fauna due to its hyper-salinity.

Therefore, both from a bureaucratic and environmental point of view, Italy has until recently ignored desalination as an alternative tool to traditional sources of water supply. Indeed, as just mentioned, it has discouraged its spread. This approach can be seen in the data on desalination plants operating in Italy. According to this analysis published in Rinnovabili – Il quotidiano sulla sostenibile ambientale, our country has only 340 desalination plants, almost all of which are small and many are currently not functioning. The sector has never really taken off, given that desalinated water accounts for 0.1% of the national fresh water withdrawal. From a quantitative point of view, the largest plant is the Saras Sarlux refinery in Sardinia, with a daily production capacity of 12,000 m³ of desalinated water. As we will see later when comparing the data with other nations, this is an extremely limited production capacity.

A quick analysis of the use of desalination worldwide shows how little this technique has been used in Italy. In a report that we published on our website some time ago, we conducted a study on the impact that the production of desalinated water has had in Saudi Arabia. Riyadh covers about half of the domestic demand for fresh water with desalination. From its original desert configuration, poor in water resources and with a diet based on few varieties of food due to the absence of fresh water[3], the kingdom of Saud currently boasts excellent agricultural production, an agri-food sector with strong surpluses due to exports and a real abundance of water. The main reason for this epochal change in Saudi society and politics is the great efficiency of the Saline Water Conversion Corporation, a state colossus that has woven the entire Arab nation with powerful desalination plants. Similarly, although to a lesser extent, there are the cases of the United Arab Emirates, South Korea, the United States, Japan and Australia, where modern and efficient desalination plants have been built to ensure a constant source of water supply.

To stay in the Mediterranean basin, we highlight the cases of Israel and Spain, two of the most technologically advanced Mediterranean nations in terms of desalination. As reported in an article by AB AQUA some time ago, produced in collaboration with the Israeli Embassy in Italy, Tel Aviv today produces – thanks to desalination – over 20% more water than it needs. In essence, desalination has allowed Israel to transform its territory, which has always been arid and parched, into a sort of open-air garden in the middle of the desert. A similar situation is found in Spain, where the entire southern part and the islands are often characterized by severe drought crises. Today Madrid, as analyzed in one of our reports, is the fourth largest producer of desalinated water in the world and the first in Europe. In the Iberian country, there are currently 765 plants operating that produce approximately 5,000,000 m³/day of desalinated water for supply, irrigation and industrial use. These are really important numbers.

As mentioned, the “Drought” Decree-Law has streamlined the rules for the construction of plants in Italy. Much remains to be done to provide our country with the necessary quantity of desalination plants capable of protecting us from the plausible water crises of the future. Nonetheless, the first important step – de-bureaucratization – has been taken. This new turning point has worried environmentalists, who have asked for strict rules for the management of brine. However, recent research has shown how this industrial waste from the desalination process can be used sustainably and profitably. As reported in our latest report, brine can be very useful in today's ecological transition. In fact, if properly treated through chemical engineering processes, brine can be used to produce lithium, an essential mineral for the production of electric batteries. Therefore, instead of spending huge amounts of capital to dispose of it or, even worse, throwing it into the sea after producing desalinated water, brine can become a key component of the circular economy associated with the sustainable production of lithium.

The short-term results of the new Italian political doctrine regarding desalination seem encouraging. In fact, a few weeks ago, the news broke of the design and financing of a large plant that, once built, will become the largest in Italy. As reported in this article, the Tara desalination plant will be built in Puglia by 2026. It will work with reverse osmosis and will desalinate the brackish spring water of the Tara River, located about fifteen kilometers from Taranto. The plant, which will produce 60,000 m³ of drinking water per day – corresponding to the needs of approximately 385,000 people – will be built by the French company Suez Group, which won the 90 million euro contract put out by Acquedotto Pugliese. The construction of the desalination plant is part of a strategy to diversify water supply, in line with the new legislation that is more favorable to this type of solution to combat drought-related water crises. As reported by Alice Scialoja in her article, from an energy perspective, the Tara desalination plant will adopt a low-impact model. The solution proposed by Suez Group, in fact, will allow for significant energy savings. In this regard, the plant will be powered by a photovoltaic system with approximately 2,000 panels, for an average annual production of over 1,200 MW to support production activity.

Conclusion

As described in this report, the combined effect of rising temperatures and the reduction of traditional water sources from which to obtain supplies will significantly increase Italian water stress in the near future. It is therefore necessary to start planning the construction of modern desalination plants that can ensure our country a greater supply of water for agricultural and industrial purposes. The Tara desalination plant, in this respect, represents an important investment made thanks to the de-bureaucratization brought about by the Drought Decree Law. The use of photovoltaic panels to power the plants would allow for virtuous and eco-sustainable management of this technique. Furthermore, the “circular” management of brine to produce lithium, in addition to reducing disposal costs, could guarantee an important source of supply of one of the most requested minerals on the global market at the moment.

The de-bureaucratization implemented by the 2023 Drought Decree Law has finally prepared all the legislative and bureaucratic tools necessary to place Italy at the same level as the main world economies in terms of desalination. The construction of the plants, which will still require time, will ensure a certain water resilience to the territories most exposed to rising temperatures and reduced rainfall. This refers, in particular, to the southern regions and large islands, which have been experiencing worrying water deficits for several years now. In addition, the northern areas will also be able to benefit from a stock of reliable resources that they can rely on in case of need. In this regard, let us not forget that the 2022 drought also caused extensive damage to Emilia Romagna and Tuscany, two regions that until a few years ago had not encountered particular cases of water deficit. In essence, the drought crises of the coming years will have a very strong impact at a national level. This means that the issue must be addressed with preventive measures and strategies of a national rather than local nature.

Given the growing need for water that will affect our entire territory in the coming years, it is suggested that in each Italian region with a sea coast, three to four large plants be built to deal with plausible drought phenomena. In addition to this, a transport infrastructure could be created on the Israeli model of the National Water Carrier (NWC)[4]. This is a complex system of pipes that, over time, has supplied the small Middle Eastern nation with precious water resources. If there were no need to use desalinated water to respond to a local crisis, it would be appropriate to have a sort of Italian National Water Carrier for the desalinated resource that passes through each region. If necessary, this water could be quickly transferred to where it is most needed. In this way, in addition to promoting fruitful cooperation between the regions, a strategic infrastructure would be available that is capable of transporting the precious “blue gold” from south to north. In fact, some of the most important Italian regions in terms of productivity – Lombardy, Piedmont, Trentino Alto Adige – do not have access to sea coasts from which to obtain desalinated water. From the perspective of integrated hydro-strategic development, a hypothetical Italian National Water Carrier could protect these highly industrial regions from a drought crisis. A plant built in Liguria or Emilia Romagna, for example, if connected with special pipes, could easily reach territories in Piedmont or Lombardy, protecting them from the devastating effects of drought.

Bibliografia

https://www.reteambiente.it/news/50987/istat-su-acqua-perdite-in-infrastrutture-idriche-restano-ele/.

_______________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________

[1] Vista l’estrema variabilità di questi dati da un anno all’altro occorre analizzare intervalli relativamente lunghi.

[2] L’evapotraspirazione è l’evaporazione diretta e traspirazione dagli organismi viventi.

[3] Basata in massima parte sul consumo di datteri e carne di cammello. La mancanza di acqua ha impedito per molto tempo all’Arabia Saudita di sviluppare un apparato agricolo efficiente in grado di soddisfare la crescente popolazione.

[4] https://abaqua.it/linnovazione-tecnologica-israeliana-al-servizio-dellefficienza-idrica-un-esempio-da-seguire%EF%BF%BC/.

De-bureaucratization of desalination plants after the 2022 water crisis

Filippo Verre - March 12, 2024

Abaqua

Via Cassia, 615

00189 Roma (RM)

© 2024. All rights reserved.

Codice Fiscale: 96584590580