Egypt and the construction of the largest artificial river in the world. Scenarios and hydro-strategic implications

Filippo Verre - July 4, 2023

* Questo paper è stato pubblicato originariamente sul sito di Silvae, la rivista tecnico-scientifica ambientale dell’Arma dei Carabinieri. A questo link è possibile consultare la pubblicazione originale. L’immagine di copertina è stata presa dal sito Middle East Monitor, consultabile al seguente link.

The technology available to man to make technical improvements in various fields reaches new horizons every year. From a hydraulic point of view, only in the last twenty years has engineering knowledge progressed so rapidly that in many nations very daring projects have been developed, capable of revolutionizing forever the ecosystems of entire regions. To cite some examples, take the Chinese case of the Three Gorges Dam. Inaugurated in 2006, it is one of the largest and most impressive hydraulic infrastructures in the world, second in size only to the Itaipú dam, located on the border between Paraguay and Brazil. With over 2,300 meters of width, it holds the world record for the most powerful hydroelectric plant, capable of satisfying 3% of the enormous energy needs of China, a country notoriously energy-hungry to say the least. To fully understand the impact that an infrastructure of this size has on the global ecosystem, consider that according to some NASA scientists, the large mass of water that has accumulated following the construction of the dam is causing a decrease in the speed of rotation of the earth, and therefore a lengthening of the length of the day, albeit by an infinitesimal value estimated at 60 billionths of a second. In itself, this variation is imperceptible to human beings. But that a human construction is capable of bringing about even very slight changes to the entire globe, says a lot about the technological progress available to our species[1].

Fig. 1:La Diga delle Tre Gole vista dall’alto

https://www.wsj.com/articles/flooding-again-threatens-chinas-three-gorges-dam-11597847951

Still on the subject of mega-dams, consider the Grand Ethiopian Renaissance Dam (acronym GERD) inaugurated on February 20, 2022. With an installed capacity of 6.45 gigawatts, it is the largest hydroelectric plant in Africa, as well as the seventh largest in the world. If for Addis Ababa the advantages of the GERD are multiple - that is, production of hydroelectric energy for domestic consumption and export markets, regulation of water flows downstream, prevention of floods, creation of many jobs, etc. - for Egypt and Sudan this impressive infrastructure has significantly reduced the inflow of water from the Nile. The data relating to the exact quantity of water resources "lost" by Khartoum and Cairo is not yet available but, according to various sources, it is many millions of m³ of water per year, enough to increase regional tension between three important African countries[2].

The spread of mega-dams in various parts of the world is a clear indication of how rapidly human technological progress is spreading, especially from the point of view of hydraulic techniques. In addition to these complex infrastructures, it is also necessary to dwell on other ideas and projects that have been gradually developed to increase the stock of water resources available to the growing world population. In Egypt, for example, a bold idea has recently been proposed: it is the New Delta Project (NDP). Considered the most innovative among the agricultural projects in Egyptian history, it aims to increase the portion of national territory intended for agriculture by almost 2.2 million acres, or approximately 9,000 km².

Egypt's "thirst" for water. A question of primary importance.

To understand the great trust and expectations that the political class and Egyptian society place in the New Delta Project, it is appropriate to take into consideration some demographic and statistical data. Currently, according to the most recent studies, Egyptian citizens are just over 107 million, making the North African country the most populous nation in the Arab world and the fourth in the African context after Nigeria, Ethiopia and the Democratic Republic of Congo. Population growth has been rapid and continuous over the last two decades, with demographic peaks that have even surpassed the most prosperous scenarios. In this regard, the Central Agency for Public Mobilization and Statistics, the government body that produces statistical and demographic projections regarding the changes within Egyptian society, in 2011 made a series of demographic forecasts on the growth of the national population. Three scenarios of expected demographic increase were offered for the twenty-year period 2011-2031: low, medium and high. In 2011, the Egyptian population stood at around 82.4 million citizens. Just a few years later, in 2013, the Egyptians were 84.6 million; this demographic increase had exceeded the highest scenario, which envisaged "only" 83 million individuals. This trend of high growth continued in the following years, effectively increasing the number of new citizens. After the increase of 1,583,000 units recorded in 2022, Cairo is powerfully on its way to touching 115 million citizens in the next few years[3]. This is an important milestone that makes Egypt a true demographic power.

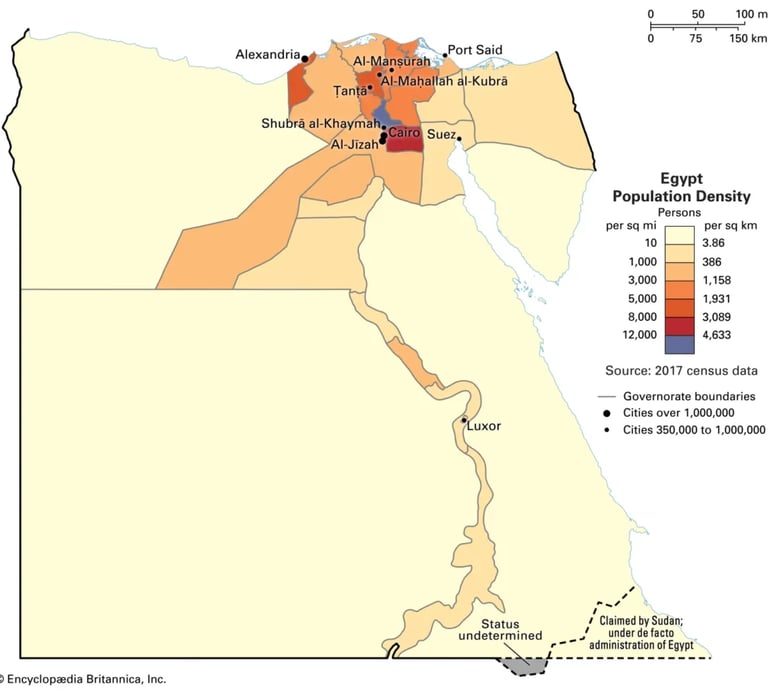

In addition to the dizzying growth in the number of inhabitants, another equally relevant fact must be taken into account that explains the urgency of increasing Egypt's water resources and arable land: population density. If we take the aggregate data into consideration, the Egyptian density is not particularly high, around 70 inhabitants/km² in a territory of over 1,000,000 km². For comparison, consider that Italy, among the most densely populated European countries, has a much higher figure: 196 inhabitants /km² against the European average of 115 inhabitants /km². However, examining a little more deeply, some evident critical issues emerge. The Egyptian population is resident along the course of the Nile River, in the vast Mediterranean delta and in some oases circumscribed in the desert.

Fig. 2: Densità abitativa egiziana (2017)

https://www.britannica.com/place/Egypt/Demographic-trends

This characteristic can also be seen by looking at the hydrographic map of the country, where cities and large urban centers are understandably located right next to the most fertile areas along the course of the great and historic river. Naturally, the portion of territory that allows the presence of human life is much smaller than the vast area belonging to the Egyptian state. In fact, only a little more than 110,000 km², corresponding to approximately 11% of the entire national territory, offer conditions suitable for permanent residence. Consequently, in light of this data, the aggregate value that certifies the Egyptian population density must be recalculated on the basis of criteria of effectiveness and reality. In essence, the density in relation to this space rises to over 1,000 inhabitants/km², with peaks that go beyond 1,500 in Cairo and in large metropolises. This value is among the highest in the world and contributes to making the Egyptian water supply and food security extremely fragile.

In addition to population growth and population density, it is worth mentioning the aforementioned GERD dam. Built on the Ethiopian portion of the Blue Nile, this large infrastructure will cause, as mentioned, a significant decrease in the water flow downstream and north over the years. Since ancient times, the Nile had represented the source of life on which many generations had been able to count on as the main source of sustenance. As is known, the ancient Egyptian civilization relied on the water of the river, considered sacred, and on the mythical and salvific "silt", that highly fertilizing natural fertilizer essential for cultivating the land at those arid latitudes. Time was marked by the floods of the river, since the year was divided into three seasons identified on the basis of the activity of the Nile. The first, Akhet, was the season of flooding; the second was called Peret and occurred when the lands re-emerged following the retreat of the waters; the third, Shomu, characterized the period of the so-called "low waters".

Not long ago this tripartite division was altered, precisely when the Egyptian government built the Aswan Dam. Completed in July 1970, this impressive hydraulic infrastructure allowed the formation of a huge artificial reservoir of over 169,000 million m³ of water capable of regulating the flow of water towards the north, controlling and preventing floods and producing large quantities of hydroelectric energy[4]. The Aswan Dam, unlike the GERD, is entirely available to Egypt. In other words, through this infrastructure it is Cairo that decides how much water to let flow or block through the dam inaugurated in 1970. Following the construction of the GERD, however, the Egyptian government is no longer the sole decision maker on the quantity of water allocated to the population living along the river. On the contrary, Egypt is very vulnerable to Ethiopian hydro-strategic decisions, which could significantly alter the water supply for many millions of Egyptian citizens and businesses. For its part, Ethiopia has every right to exploit the portion of the river located in its territory for energy and economic purposes. Let us not forget, in this regard, that the hydroelectric energy obtained from the exploitation of the GERD will also be used to bring electricity and light to thousands of Ethiopian families, whose electrical needs are not always guaranteed by the national grid [5].

The New Delta Project: data, forecasts and hydro-strategic implications

Recent events, including the inauguration of the Ethiopian dam and the outbreak of war in Ukraine, have made a solution to the long-standing issue of Egyptian food security more urgent than ever. In fact, if the GERD has reduced the percentage of water resources coming from the Nile, the outbreak of war has caused first a slowdown and, subsequently, a blockage of the supply of Ukrainian foodstuffs intended for Egyptian domestic consumption. It should be emphasized that Egypt is among the countries most affected by the effects of the war in Ukraine as it depends heavily on imports for the supply of wheat, corn, soybeans and oil; a significant portion of these imports come from Russia and Ukraine[6]. Egypt, given the small percentage of national territory to dedicate to the production of agricultural goods, is forced to rely heavily on foreign markets for food needs. To understand this foreign dependence in detail, consider some data.

Agriculture in Egypt is the main source of income in rural areas; However, this income is seriously insufficient to guarantee a decent life for families, especially in Upper Egypt and in large cities. This is because over 90% of Egypt's surface is desert and only a little more than 3% of the territory is used for agriculture. Most Egyptian farmers are small landowners who suffer from low land productivity and limited government support. It should be noted, however, that agriculture, although it represents 11.3% of GDP, employs 28% of the national workforce and 45% of all employed women. Therefore, despite low productivity, the number of workers assigned to Egyptian agriculture is quite high. Precisely because of a low-productivity agricultural sector, Egypt is a net importer of food products, purchasing 40% of the food consumed abroad, for a total value of over 3 billion dollars per year.

Over time, the government has attempted various ways to reverse this not exactly virtuous trend. The main strategy adopted has involved increasing the cultivable land, in order to increase the food produced internally and avoid a massive use of imports. This approach, in fact, has some obvious critical issues. On the one hand, being an importer of essential goods such as food, the Egyptian state is left unprotected in terms of internal security. In fact, in the event of a conflict with another nation or, as in the case of the war in Ukraine, in a war scenario even if far from North Africa, military actions can slow down or even interrupt the food supply, causing serious socioeconomic damage to the country. Furthermore, imports weigh negatively on the balance of payments, so a part of the tax revenue leaves the Egyptian system and never returns except in the form of food represented by corn, wheat, oil and barley.

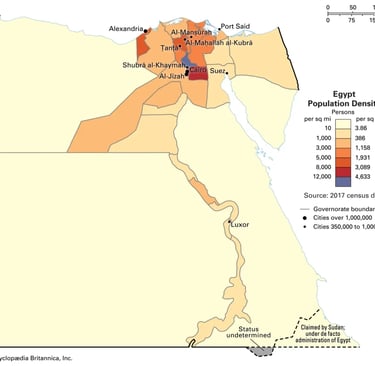

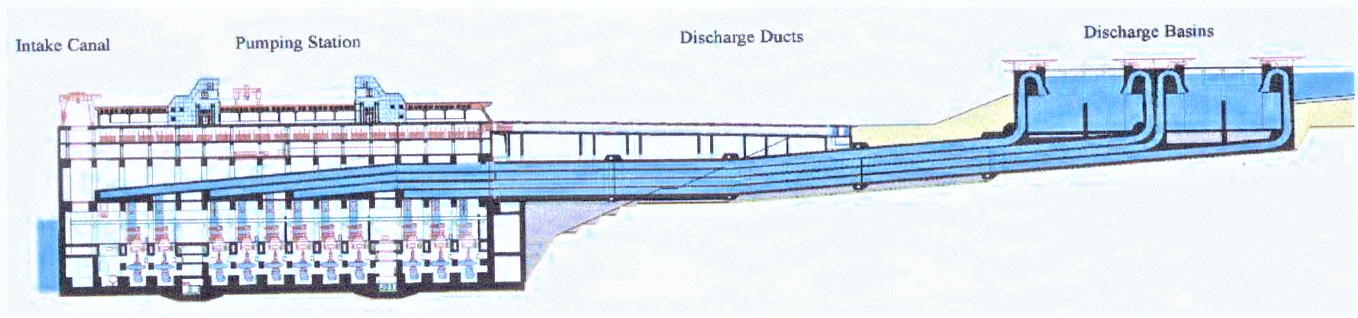

In 1997, Cairo launched a bold initiative dubbed the New Valley Project with the aim of increasing the country's food security. The stated goal was to increase the arable land in Egypt's southern desert by 500,000 acres (about 200,000 hectares). The water needed to irrigate the new lands for agricultural production would be supplied by a canal connected to Lake Nasser,[7] an artificial reservoir located between Egypt and Sudan that was created following the construction of the Aswan Dam. In 2005, Hosni Mubarak, the then leader of the nation, inaugurated the Mubarak Pumping Station, the main hydraulic infrastructure of the project capable of ensuring a constant supply of water to the portion of territory chosen by the government to increase agricultural production.

Fig. 3: Immagine della Mubarak Pumping Station

https://icat.com.eg/portfolio/mubarak-pumping-station/

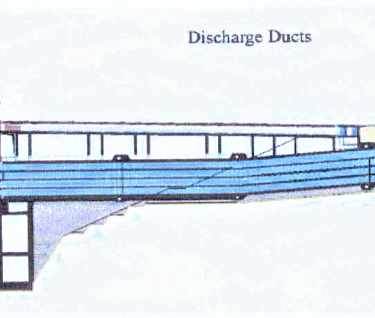

Fig. 4: Meccanismo di funzionamento della Mubarak Pumping Station

https://icat.com.eg/portfolio/mubarak-pumping-station/

Despite this, no significant progress has been made since then from a quantitative point of view regarding the hectares under cultivation. In fact, despite a lot of public money allocated – the Mubarak Pumping Station alone cost almost 500 million dollars[8] – the project ran aground and did not see the much-desired completion. Similar initiatives have also been taken in Sinai, an arid peninsula on the border with Israel where the Egyptian government has tried to increase the percentage of land dedicated to agriculture. Even in this case, despite valid initiatives, the results have been modest.

The New Delta Project is part of this framework of large and visible initiatives sponsored and financed by the Egyptian government to ensure greater food security. As mentioned, Cairo has the objective of building the longest artificial river in the world which, from the government's perspective, will supply water to a truly notable portion of territory, almost as large as our Basilicata. Water resources will be supplied by the powerful Al-Hamam plant, the largest agricultural wastewater treatment plant in the world. At full capacity, Al-Hamam will treat six million m³ of water per day that will be used to irrigate the numerous fields that the government intends to convert from desert to arable land. The artificial river will be built together with a long network of canals into which the water reconverted by the plant will be fed to be taken from time to time for irrigation purposes. The mechanism is similar to that of a giant water artery from which to draw in case of need.

An interesting aspect of the New Delta Project concerns its so-called integrated approach. In Cairo's plans, in fact, the increase in arable land should translate into a reduction in overpopulation in urban areas, which are clearly struggling with population density. The project for the construction of the new capital of the Egyptian state should be seen in this light, not by chance to be built near the artificial river. The new city, for the moment still without an official name and indicated as New Administrative Capital (NAC), will be located in the Cairo governorate about 45 kilometers east of the current capital, whose traffic congestion and evident overpopulation constitute serious critical issues. Specifically, Cairo, including the area belonging to the so-called Greater Cairo, is the largest metropolitan area in Egypt, the largest urban area in Africa, the Middle East and the Arab world and the sixth largest metropolitan area in the world. With a total population estimated at over 21,000,000 inhabitants on a surface area of 1,709 km², in certain areas it has a record density that reaches 12,230 inhabitants/km²[9]. According to the project, the city will become the new administrative and financial capital of the State, hosting the main government offices and ministries, the seat of Parliament and foreign embassies.

Fig. 5: Centrale di Al-Hamam

https://energy-utilities.com/consortium-wins-egypt-wastewater-contract-news111156.html

The strategic implications of the New Delta Project are evidently various. First of all, the construction of a large hydraulic infrastructure capable of transporting a lot of water could revolutionize not only agricultural production but also the urban geography of Upper Egypt. The project for the new capital, in fact, launched in 2015, is necessarily linked to the increase in water resources that will be available following the completion of the river. The NAC will be built on the model of a modern smart city for which, in addition to offices, houses, hospitals, schools and so on, many green parks, fountains and artificial lakes are planned[10]. Inevitably, to achieve all this, water will be one of the essential elements on which to plan such a bold project, especially given the aridity of the region. Furthermore, the increase in cultivable land will cause an inevitable displacement of people who currently reside in the metropolitan areas of Cairo. The government expects that several hundred thousand Egyptians will be employed in the agricultural sector that will be formed following the completion of the project. This should translate into the much-desired demographic and housing relief of Egypt's large cities, especially Cairo. Finally, the increase in domestic food production should reduce the imports of agricultural goods that Egypt is forced to make to satisfy its growing population.

Conclusion

As can be seen from this brief analysis, the expectations that the Egyptian government places on the New Delta Project are many and with potentially revolutionary implications for various national strategic sectors. However, in the face of an undoubtedly bold vision, it is appropriate to mention a series of critical issues that exist regarding both the feasibility and sustainability of the final project. The construction of the longest artificial river in the world is an idea that certainly strikes the collective imagination and stimulates the curiosity of experts and ordinary citizens. Although on paper this project is approved, it is not clear how the Egyptian government intends to find the large amount of water needed to increase the surface area of cultivable land and to irrigate the new administrative capital under construction with the precious liquid. Egyptian authorities have not released details on the number of inhabitants that will populate the city. To be built on an area of approximately 720 km², the NAC will not be a megalopolis but will still have a significant population. According to some projections, the inhabitants will be between 3 and 5 million with the potential to host up to 6.5 million citizens[11]. This means that the water resources to be allocated just for the supply of the new city will be very significant. To this, must be added the amount of water needed to irrigate over 9,000 km² of desert territory to be used for agricultural production, according to the government's plans.

It is difficult to estimate how much water is actually needed for both of these projects. However, it is intuitive that it would be a huge amount, in the order of tens of millions of m³ per day and several billion m³ per year. According to the Egyptian government, the main source of supply is the water used to irrigate the fields which, once cleaned and treated with the help of the aforementioned Al-Hamam plant, will guarantee a constant flow of resources to be introduced into the artificial river. In addition to this, drainage channels will be used to convey rainwater and waste water to the purification plant. This will increase, according to the authorities, the final quantity of water available. Since it is not a very rainy area, it is conceivable that the contribution that rainwater will have to the final water basket will be small. Furthermore, the Al-Hamam plant, as mentioned, has a water resource reconversion capacity of about six million m³ per day. This means that only at full capacity is this plant capable of generating the aforementioned quantity. It is very unlikely that Al-Hamam will be at full capacity every day throughout the year. And even if it were, doing a quick calculation, the plant would generate just over two billion m³ of water per year. This is certainly a large quantity but not enough to guarantee the supply of a new large city and over 9,000 km² of agricultural area. Let us not forget, in fact, that the quantity of water intended for agricultural production is very high[12].

Analyzing the feasibility and sustainability of the New Delta Project, one gets the feeling that Cairo has taken a path that is certainly bold but very difficult. It is not clear what the main problem that Egypt intends to solve is. If the lack of water is the main challenge that the North African country is trying to address, it would perhaps be desirable to favor a strategy based on maximizing water resources with less ambitious and more effectively achievable ideas. For example, taking Saudi Arabia's water policies as a model[13], Cairo could equip itself with modern desalination plants to be placed in strategic areas. Being on two seas - the Mediterranean and the Red Sea - Egypt has almost 2,500 km of coastline on which it could build an integrated industrial desalination system. These plants, thanks to the most recent research, are able to function very well even with solar energy, which is abundant both in the delta and on the desert side overlooking the Red Sea.

Furthermore, the idea behind the New Delta Project - increasing the surface area of cultivable land - appears to be conditioned by a quantitative approach, that is, based on the merely numerical increase of hectares to be subjected to agricultural production. First of all, the assumption according to which more cultivated land equals greater agricultural production is not always realized. Also because, more than greater production, it would be desirable to increase the productivity of a land. Furthermore, a larger agricultural surface area entails a larger water resource to be allocated to irrigation purposes, with a consequent increase in the water needed in an already rather arid territory. With a different approach, focused on the quality of the result rather than the quantity, the same results could be achieved with less effort. For example, take the case of the modern water policies adopted by Israel, which for decades has used minimal quantities of water to irrigate its fields. This is Drip Irrigation, the drip irrigation that has revolutionized agriculture in the small Middle Eastern country and beyond. In many respects, Israel is experiencing a similar situation to Egypt. With due geographical and demographic proportions, Tel Aviv has seen its population double in a short time in the last few decades, which is settled on a limited surface area and often subject to serious tensions. Today, the Israeli state produces 20% more water than is necessary to satisfy its growing population and a highly water-hungry modern industrial apparatus [14].

Fig. 6: Drip Irrigation

https://www.agrivi.com/blog/drip-irrigation-as-the-most-efficient-irrigation-system-type/

Furthermore, always taking the case of Saudi Arabia as a model, Cairo could increase the use of the so-called Center Pivot Irrigation, or central pivot irrigation. This method uses a mechanical system composed of a mobile tube, rotating around a fixed point, from which water comes out with the sprinkler irrigation technique. In this way it is possible to circumscribe the land that one wants to cultivate and to use moderate water resources to produce a certain agricultural product. Saudi Arabia has made copious use of this technique to cultivate an increasing quantity of land with a reduced irrigation consumption, which, as we have seen, represents the highest percentage of water use in the world. In this case too, the qualitative approach has paid dividends, since Riyadh, at the moment, despite a huge desert surface, is a nation extremely rich in water with a powerful internal agricultural production.

Fig. 7: Center Pivot Irrigation

https://www.abc.net.au/news/rural/2019-11-17/wa-pastoralists-attempt-to-drought-proof-using-centre-pivots/11663698

In conclusion, it seems that with the New Delta Project Cairo has devised a solution to multiple problems, namely the irrigation of a vast area and the supply of a new large urban agglomeration currently being completed. The feeling is that the Egyptian side has made an assessment based on a “pharaonic” vision. Naturally, this article does not intend to question the work of experts and technicians who have created a series of very sophisticated and detailed projects. Without a doubt, in the face of multiple critical issues, Egyptian engineers are perfectly capable of achieving their goals. Nonetheless, even in light of recent projects that have not been completed, one cannot help but notice that the NDP represents a colossal project whose rationale seems to be based more on showiness than effectiveness. This is also suggested by the narrative associated with the activities. The construction of the “largest artificial river in the world,” coupled with the “largest agricultural wastewater treatment plant in the world,” is perhaps more of a call to Egyptian national pride than a solution to the problem of water shortage. Also because, as demonstrated by the cases of Israel and Saudi Arabia, there are much less sensational but decidedly effective strategies.

Riferimenti Bibliografici

Bressanelli C, 2019, Abu Simbel, il trasloco del faraone, in “Il Corriere della Sera”.

Buccianti A., 2015, Egypte: une nouvelle capitale pharaonique, in “France 24”.

Cleveland C., 2010, China’s Monster Three Gorges Dam Is About To Slow The Rotation Of The Earth, in “Business Insider”.

Gebreluel G., 2014, Ethiopias Grand Renaissance Dam: Ending Africas Oldest Geopolitical Rivalry?, in “The Washington Quarterly”, Vol. 3 Issue 2, pp. 25-37.

Johns T., 2015, Egypt unveils plans to build new capital east of Cairo, in “BBC News”

Marroni C., 2023, Egitto, il gigante africano colpito dalla crisi alimentare per il conflitto in Ucraina, in “Il Sole 24 ore”.

Natali R., 2022, GERD: La grande diga della rinascita etiope, in “AB AQUA - Think Tank di Idro-Strategia”.

Palamidesse M., 2022, Etiopia, la Grand Ethiopian Renaissance Dam è attiva. Cresce la tensione regionale, in “Focus on Africa”.

Verre F., 2021, Le politiche idriche dell’Arabia Saudita, in “AB AQUA - Think Tank di Idro-Strategia”.

Verre F., 2023, L’innovazione tecnologica israeliana al servizio dell’efficienza idrica. Un esempio da seguire, in “AB AQUA - Think Tank di Idro-Strategia”.

Walker B., 2015, Egypt unveils plan to build glitzy new capital, in “CNN”.

_________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________

[1] Per maggiori dettagli: Cutler Cleveland, China’s Monster Three Gorges Dam Is About To Slow The Rotation Of The Earth, in “Business Insider”, 18 giugno 2010, disponibile al seguente link: https://www.businessinsider.com/chinas-three-gorges-dam-really-will-slow-the-earths-rotation-2010-6?r=US&IR=T.

[2] Matteo Palamidesse, Etiopia, la Grand Ethiopian Renaissance Dam è attiva. Cresce la tensione regionale, in “Focus on Africa”, 21 febbraio 2022, disponibile al seguente link: https://www.focusonafrica.info/etiopia-la-grand-ethiopian-renaissance-dam-e-attiva-cresce-la-tensione-regionale/. Goitom Gebreluel, 2014, Ethiopias Grand Renaissance Dam: Ending Africas Oldest Geopolitical Rivalry?, in “The Washington Quarterly”, Vol. 3 Issue 2, pp. 25-37.

[3] Il numero delle nascite registrate durante l’anno appena trascorso è stato di 2.183.000 milioni, pari a una media di 249 nascite l’ora, di 4 al minuto e di 14 ogni secondo. https://www.macrotrends.net/countries/EGY/egypt/population-growth-rate.

[4] Quando fu decisa la costruzione della grande diga, il cui invaso avrebbe sommerso per sempre i templi costruiti da Ramses II nel XIII Sec. A.C., l’UNESCO lanciò una vasta campagna per cercare una soluzione che consentisse di salvarli. Il progetto venne messo a punto da un’azienda svedese e l’italiana Impregilo, che nel frattempo ha cambiato nome in We Build, ricevette l’incarico si smontare i templi, sezionati in 1.030 blocchi, e di costruire una collina artificiale poco distante che sarebbe diventata la nuova dimora dei preziosi reperti archeologici. L’Italia, visto il prezioso contributo nella vicenda, ha inoltre ricevuto dei doni dal governo egiziano, come ad esempio il tempio di Ellesija, ora conservato al Museo egizio di Torino. Cecilia Bressanelli, Abu Simbel, il trasloco del faraone, in “Il Corriere della Sera”, 4 febbraio 2019, disponibile al seguente link: https://www.corriere.it/la-lettura/19_febbraio_04/lavori-diga-di-assuan-50-anni-salini-impregilo-a4c90218-2878-11e9-9261-1188ee60e68e.shtml?intcmp=googleamp.

[5] Per maggiori dettagli sulla vicenda si rimanda a Roberto Natali, GERD: “La grande diga della rinascita etiope”, in “AB AQUA – Centro Studi Idrostrategici”, 10 giugno 2022, disponibile al seguente link: https://abaqua.it/gerd-la-diga-della-grande-rinascita-etiope%EF%BF%BC/.

[6] Carlo Marroni, Egitto, il gigante africano colpito dalla crisi alimentare per il conflitto in Ucraina, in “Il Sole 24 ore”, 15 marzo 2023, disponibile al seguente link: https://www.ilsole24ore.com/art/egitto-gigante-africano-colpito-crisi-alimentare-il-conflitto-ucraina-AE88Uo4C.

[7] Il Lago Nasser si formò tra il 1958 e il 1970, anno in cui venne inaugurata la Diga di Assuan.

[8] Per maggiori dettagli si rimanda a: https://www.water-technology.net/projects/mubarak/.

[9] Oltre ad un “presente” complicato sotto il profilo demografico, le previsioni del governo prevedono che la metropoli cairota possa crescere fino a 40 milioni di abitanti entro il 2050. Per ulteriori previsioni si rimanda all’articolo di Alexandre Buccianti, Egypte: une nouvelle capitale pharaonique, in “France 24”, 15 marzo 2015, disponibile al seguente link: https://www.rfi.fr/fr/moyen-orient/20150315-egypte-une-nouvelle-capitale-pharaonique-le-caire-al-sissi.

[10] Stando al progetto, la città avrà anche un parco di dimensioni doppie rispetto al Central Park di New York.

[11] Thomas Johns, Egypt unveils plans to build new capital east of Cairo, in “BBC News”, 13 marzo 2015, disponibile al seguente link: https://www.bbc.com/news/business-31874886. Brian Walker, Egypt unveils plan to build glitzy new capital, in “CNN”, 16 marzo 2015, disponibile al seguente link: https://edition.cnn.com/2015/03/14/africa/egypt-plans-new-capital/.

[12] Circa il 70% dell’acqua consumata sulla Terra è impiegata per l’uso agricolo, il 20% per l’industria, il 10% per gli usi domestici.

[13] Per maggiori dettagli si rimanda a Filippo Verre, Le politiche idriche dell’Arabia Saudita, in “AB AQUA – Centro Studi Idrostrategici”, 28 novembre 2021, disponibile al seguente link: https://abaqua.it/le-politiche-idriche-dellarabia-saudita/#:~:text=Il%20primo%20pilastro%20delle%20misure,risorse%20idriche%20di%20tipo%20marino.

[14] Per maggiori dettagli sulle moderne politiche idriche di Israele si rimanda a Filippo Verre, L’innovazione tecnologica israeliana al servizio dell’efficienza idrica. Un esempio da seguire, in “AB AQUA – Centro Studi Idrostrategici”, 15 febbraio 2023, disponibile al seguente link: https://abaqua.it/linnovazione-tecnologica-israeliana-al-servizio-dellefficienza-idrica-un-esempio-da-seguire%EF%BF%BC/.

Abaqua

Via Cassia, 615

00189 Roma (RM)

© 2024. All rights reserved.

Codice Fiscale: 96584590580