GERD: “The Great Dam of Ethiopian Renaissance”

Roberto Natali - June 10, 2022

* L’immagine di copertina di questo paper è stata presa dal sito Inside Arabia, consultabile al seguente link: https://insidearabia.com/tensions-with-egypt-and-sudan-could-make-ethiopias-dam-the-curse-of-the-nile/

Introduction

Since elementary school, studying the ancient Egypt of the pharaonic dynasties, we have learned about the vital importance of the floods of the Nile River, the layer of fertile silt left behind when the waters receded, and the consequent and strong increase in agricultural production carried out in the vast areas of land adjacent to its banks. Agricultural products and pastures for livestock have been a source of wealth for those populations for millennia, thanks to the periodic gift of the most important African river. And even today, most of the country's population (about 90%) lives concentrated along the fertile areas of the sacred river (including the great delta) and even the country's industrial districts have been able to develop thanks to the precious water resource provided by the Nile.

However, due to its extension of over 6,852 km, this majestic river is not only the longest in the world, but also represents an indispensable trans-border waterway, since it crosses various African nations. Therefore, not only for Egypt, but also for Sudan, South Sudan and Ethiopia, it has been a fundamental resource and an essential source of life for the populations living there since time immemorial. And it is precisely on the Ethiopian plateau that the Blue Nile originates, a powerful river that supplies the Nile with 62% of its water mass. Also for Addis Ababa, evidently, the great river represents a source of wealth that is not indifferent from many points of view. In particular, to counteract the lack of energy resources, the Ethiopian government has decided to make a significant investment in hydroelectric energy: thus was born the GERD, the Great Ethiopian Renaissance Dam, a work whose construction presents numerous and delicate environmental and political implications. Below we will examine the main elements of a controversial issue that involves several actors and proves to be an element of extreme strategic importance.

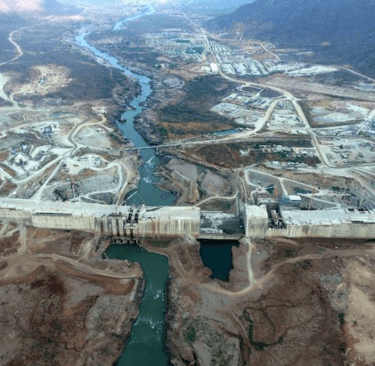

Fig. 1: La struttura della GERD sul Nilo Blu

https://www.greenstart.it/energia-idroelettrica-per-letiopia-la-diga-gerd-tra-egitto-e-metano-29142

The sacred river for Egypt

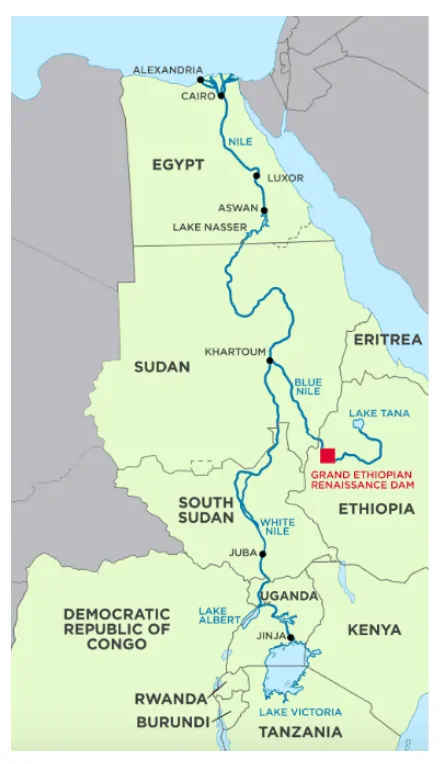

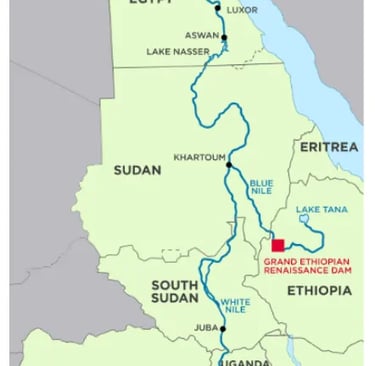

As mentioned above, the extreme importance of the Nile certainly derives from its length, which places it in first place on the world scale (followed by the Amazon River with 6,180 km), but also for its indisputable contribution to the economies of the regions it crosses. When we speak generically of the Nile, we mostly refer to the Egyptian stretch of the river that then flows into the Mediterranean Sea. In reality, it is formed by the confluence of the White Nile and the Blue Nile, which meet in the Sudanese capital, Khartoum. The first is an emissary of Lake Victoria, which laps the territories of Kenya, Tanzania and Uganda, while the second descends from Lake Tana, located in the mountainous region of Ethiopia. Naturally, the Nile is also fed by numerous respectable waterways coming from relatively distant regions, including, with reference to the White Nile, some tributaries of the Kagera, the main tributary of Lake Victoria. It is in this region of difficult access that repeated and adventurous expeditions took place during the mid-nineteenth century in search of the sources of the Nile.

Fig. 2: Punto esatto di confluenza tra Nilo Bianco e Nilo Azzurro

https://www.aramcoworld.com/Articles/March-2018/Khartoum-A-Tale-of-Two-Rivers

In addition to the positive effects on agricultural production, the Nile represents another huge source of wealth for modern Egypt, coming from tourism and, more generally, from the navigability of the river. Even if the fluid flow is hindered in various places by cataracts, shallow water areas, islets and rocky structures, navigation on the river continues to be a very respectable item for the Egyptian economy, with particular regard to tourist cruises on the Nile and the transport of goods and raw materials between the various cities, among which Khartoum, Aswan, Luxor and the metropolis of Cairo stand out. Navigation is also supported by the winds that, especially in winter, blow southwards channelling themselves into the valley, while towards the north the boats are helped by the natural flow of the current. Naturally, it should be noted that the tourism sector linked to navigation on the Nile has also recently suffered serious losses, due to the global health crisis caused by the Covid-19 infection, just as in previous years a collapse in the tourist flow had occurred following Islamist terrorist attacks.

Fig. 3: Feluche sul Nilo

https://www.travelworld.it/egitto-assuan-dove-il-nilo-crea-la-vita/

The Dam and Ethiopia's Reasons

We have seen how the Nile has always been a kind of lifeblood for the Egyptians who, in the past, had even developed a calendar based on the periodic flooding of the river. But we cannot ignore the importance that the Blue Nile, the branch of the river that flows in Ethiopia, has for Addis Ababa. In fact, the reasons of this country that, through the construction of the great dam, plans to be able to produce electricity in very significant quantities both for its own economic development and with the prospect of being able to export a large share of it, also appear well defensible.

It has long been said that the power attributed to Ethiopian rulers to divert the flow of the Blue Nile causing famine in Egypt. As early as 1958, the last Ethiopian emperor, Haile Selassie I, proposed building a dam on the Blue Nile, but only in April 2011, with the start of construction of the GERD, did these fears on the part of Egypt and Sudan come to fruition. This great work, which blocks the Blue Nile not far from the border with Sudan, in the western region of Ethiopia, is the seventh largest dam in the world and in any case the largest on the African continent. Its dimensions are in fact impressive: 155 meters high and 1,780 meters wide, the GERD includes a reservoir of approximately 74,000 meters³ that covers a surface area of 1,874 km² (we can imagine a space larger than half of the Italian region of Valle d'Aosta). Built by the Italian company Salini Impregilo Costruttori (now We Build), the structure, as well as the energy produced, belongs to the Ethiopian State, which financed the work with a very significant investment of approximately three billion dollars. However, some banks belonging to the Chinese State, particularly active in the construction of infrastructure in Africa[1], also took part in the financing with 1.8 billion dollars, bringing the total cost of the work to almost 5 billion dollars. Its operation, currently 84% completed, is based on the power of 16 turbines, capable of generating 16,153 Gigawatt hours every year, with a maximum power of 5,150 Megawatts.

Fig. 4: L’imponente struttura della GERD vista dall’alto

https://www.powermag.com/tensions-intensify-as-ethiopia-readies-to-start-gerd-mega-dam-turbines/

Filling the reservoir will still take a long time, but it should be considered that with the GERD, Ethiopia will be able to satisfy its energy needs by producing clean energy, which can also be resold to Egypt, Sudan, Uganda and Djibouti.

In addition to the energy benefits, the induced effect also appears considerable, since approximately 10,000 people were employed to build the project and it has been estimated that, when the reservoir is sufficiently full, it will be possible to produce between 6,000 and 7,000 tons of fish products annually, as well as generate a significant tourist attraction. The need for new energy, on the other hand, must also be related to the demographic growth recorded in Ethiopia. The population, which currently amounts to over 117 million, is recording a growth rate of 2.5%, not in line with the demand for energy, which is also necessary for the production of agricultural and industrial products. Ultimately, it seems that Addis Ababa has well assessed the convenience from this point of view, since before the construction of the GERD the hydroelectric potential of the country was exploited only around 8%.

As in other cases already analyzed by AB AQUA, the construction of a hydraulic work of the size of the GERD certainly produces some concerns in terms of environmental and social sustainability. The production of clean energy, in fact, will not overcome the important problems linked to the irreversible modification of the environment and its biodiversity. The transformation of the valley into a vast lake can only have heavy effects on the populations that previously inhabited it and that cultivated it in various areas, now forced to abandon the places of their traditions. Equally important is the impact that the creation of the reservoir will have on local flora and fauna. There is still a debate among international experts on this issue, because if the economic effects of the GERD project are quite evident, the negative impacts on the environmental balance seem to have been taken into less consideration, with insufficient planning, lacking the necessary synergy between central and local authorities and, above all, the participation of public opinion.

If the fears expressed for years by Egypt seem to have an objective foundation and the complaints towards Addis Ababa in relation to the construction of the work are understandable, it should be noted that the Egyptian leadership itself is well aware of the fact that for the same reason, that is, the production of electricity, various dams were also built in Egypt at the time. Among these, we should mention those of Ziftah, Assiout, Hammadi, Esna and, above all, the two large infrastructures of Aswan, whose construction, in the Seventies, made it necessary to move various temples, including the very famous one of Abu Simbel which, otherwise, would have been submerged by the waters of Lake Nasser. Moreover, this imperative need to increase hydroelectric power production even in the country of the Pharaohs has strongly limited the flooding of the river and the subsequent deposition of fertile silt, with various critical effects, including the need to use chemical fertilizers with a strong polluting effect on the soil and on the Nile itself.

Fig. 5: Il lungo corso del Nilo Bianco e Azzurro e il sito della GERD etiope

https://www.insightsonindia.com/2020/03/20/insights-into-editorial-a-dam-of-contention-in-africa/

Dispute, water control and negotiations

No one has ever questioned the fact that the Nile has always been the main source of water for Egypt and Sudan, satisfying 90% of domestic demand; for this reason, it has a highly strategic character. In order to regulate the management of the river's waters, in 1929 and 1959 the two States signed agreements of which, however, Ethiopia was not a party. Evidently, the GERD project and the start of work in 2011 have given Addis Ababa a primary role in the issue that has necessarily required and provoked a heated debate between the three States most interested in the construction of the work: Ethiopia, Egypt, Sudan. All in all, Sudan, although involved, has not expressed major objections to the construction of the dam. On the contrary, Egypt has not failed to express its ancient fears of having to depend on Ethiopia for its water supply. Over the course of the next decade, there were alternating phases, characterized by negotiations, often strong tensions (and sometimes even veiled threats), circumstances that in April 2021 led the three parties to suspend negotiations.

It should be remembered that an agreement had already been reached in 2010, in Entebbe (Uganda), which identified a criterion for the exploitation of the river's waters based on the number of inhabitants, climatic conditions, as well as the economic needs of the various countries involved, including Burundi, Rwanda, Tanzania, Uganda and Kenya. But this proposal had no real follow-up.

Beyond the fears for the evident and described dependence on Ethiopian decisions regarding the management of the river's water, among the reasons for irritation of Egypt and Sudan (but more than Egypt) was the fact that in 2011 Addis Ababa had begun work on the dam without prior notice to the neighbors interested and affected by the effects of the project. In particular, in recent years the governments of Addis Ababa and Cairo have accused each other of not respecting international norms on the management and exploitation of the Nile water. Egypt has argued that a project like the dam could not be built without its consent, due to the two (mentioned) international agreements with Sudan, one dating back to 1929, during the colonial era, and the other to 1959: the first gives Egypt the power of veto on the construction of infrastructure along the Nile; the second establishes that Egypt is entitled to approximately 66% of the Nile waters, and 22% to Sudan.

The Ethiopian government, however, replied that it does not recognize the agreements, since – as we said – they were signed without involving Ethiopia, and therefore has the right to develop its own project (on the other hand, it is hardly sustainable that a country should be bound by an agreement that it has not signed). In 2010, Addis Ababa had agreed with the other countries in which the Nile basin is divided – Egypt and Sudan excluded – to carry out projects along the river even without Egyptian consent. Furthermore, Ethiopia has always maintained that the new dam will have no impact on the amount of water that will reach Egypt, contrary to what the Egyptians feared. This dispute has inevitably triggered diplomatic crises between the three countries, also generating tensions in the entire Horn of Africa region, already made unstable by the Tigrai crisis, the transition to democracy in Sudan and the civil war in South Sudan.

Addis Ababa is certainly in a very advantageous position and it is therefore not surprising that, in light of the historical importance described that the Nile has for the country of the Pharaohs, Cairo itself had to take a conciliatory step, showing greater interest in defining an agreed and shared management of the waters, showing itself to be a reasonably more active part and asking for the urgent resumption of negotiations relating to the Grand Renaissance Dam on the Blue Nile, in order to reach a fair agreement favorable to mutual interest. The Egyptian Prime Minister, Mustafa Madbouly, in fact, recently reiterated through an official statement the will to re-establish a discussion table with Addis Ababa, declaring that "Egypt wishes to resume negotiations as soon as possible, with the aim of accelerating the resolution of technical and legal disputes in order to reach a fair, balanced and equitable agreement, taking into account the scarcity of water in Egypt and its dependence, mainly on the waters of the Nile". After intense work by their respective diplomatic chancelleries, as well as following repeated invitations from the United Nations Security Council, the two prime ministers of Egypt (Al Sisi) and Ethiopia (Abiy Ahmed) signed an agreement in June 2021 for closer and more fruitful collaboration.

Conclusions

Last February, Ethiopian Prime Minister Abiy Ahmed flipped the switch to start the turbines that power the first phase of the GERD project, so that Addis Ababa began producing electricity through its controversial and massive hydroelectric plant. The long diplomatic quarrels with the two countries located downstream of the Nile basin seem to have been put aside for the moment, but they are not really over, as the main element of the case has not disappeared, namely the reasonable fear of Khartoum and Cairo that the GERD project could, even partially, reduce their water resources, at least until the reservoir on the Blue Nile is filled. The moments of stalemate in the negotiations, on the other hand, concerned precisely this aspect, because Cairo required filling times of the hydroelectric basin of at least seven years, in order to receive at least forty billion cubic meters of water every year, while Addis Ababa considered a period of three years appropriate, in order not to delay its development plans too much.

We also considered Ethiopia's difficulties in terms of the greater need for energy, in this case hydroelectric, necessary for agricultural purposes, for civil use by the population, for industrial use and ultimately for the development of the country. Ethiopia, in fact, is the second most populous country on the African continent and, according to studies carried out by the World Bank, also the one with the second largest electricity deficit. About two thirds of the population does not have an electricity connection and, to quote the Prime Minister: "the main interest of Ethiopia is to bring light to the 60% of the population that suffers in the dark and save the work of our mothers, who carry wood on their shoulders to be able to have a little energy".

AB AQUA has already addressed in previous writings some aspects, including the legal one, of the issue of trans-border rivers[2]. The case of the GERD also reiterates the need for a supranational regulation that, due to the enormous strategic value of the waterways, does not leave to the single State the unilateral and indisputable initiative to make use of the waters of the rivers that cross its territory, for the sole fact that this is located upstream of other countries.

Even in this regard, it is useful to remember that something is moving within the international community and public international law. One of the topics of interest foreseen in the context of the various International Conferences on water at the UN level scheduled for 2022 and 2023, concerns in fact precisely trans-boundary waters, including underground, with the aim of identifying balanced formulas to be shared, and possibly inserted into codified International Law, in order to reduce tensions and conflicts as much as possible, leaving the peoples who live on waterways the possibility of benefiting from them and the serenity of being able to still consider them "their rivers". Let us not forget, in fact, that it is precisely on rivers that the largest cities and the most ancient civilizations were born.

_________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________

[1] Il Centro Studi AB AQUA si è già diffusamente occupato dell’interesse cinese in Africa per ciò che concerne questioni idro-diplomatiche. Per maggiori dettagli si rimanda a: L’Idro-diplomazia come strumento di politica estera: il caso cinese della Sinohydro Corporation, disponibile al seguente link: https://abaqua.it/lidro-diplomazia-come-strumento-di-politica-estera-il-caso-cinese-della-sinohydro-corporation/.

[2] Maggiori dettagli su questa materia sono consultabili presso alcuni studi presenti nel nostro sito. I titoli sono “La navigazione nel bacino idrografico del Rio delle Amazoni” e “Il grande valore idro-strategico del Tibet”, rispettivamente ai seguenti link: https://abaqua.it/la-navigazione-nel-bacino-idrografico-del-rio-delle-amazzoni/ e https://abaqua.it/il-grande-valore-idro-strategico-del-tibet/.

Abaqua

Via Cassia, 615

00189 Roma (RM)

© 2024. All rights reserved.

Codice Fiscale: 96584590580