Brief physical notes on the area

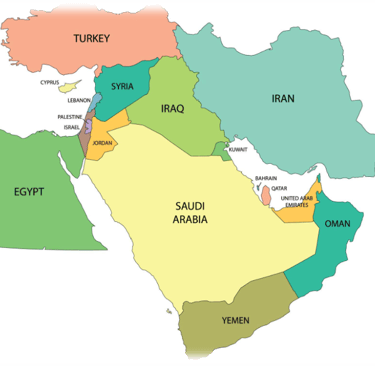

To begin, it is appropriate to identify what is meant by "Middle East", an expression used since the mid-twentieth century to identify this vast area. More recent is the use of the term "Greater Middle East" which indicates, precisely, the territory that extends from the eastern Mediterranean and the Persian Gulf towards the Caspian Sea and the Caucasus up to the western borders of China[1]. It is not a simple geographical entity, but a reality steeped in history that has been forced to model itself on a great variety of political, economic and cultural factors. It can therefore be said that the Middle East is a historical-geographical region that includes the African and Asian countries that overlook or gravitate towards the eastern Mediterranean[2] such as Turkey, Israel, Egypt etc., and those located on the Persian Gulf such as Iraq, Iran etc.

Fig. 1: Cartina politica del Medi Oriente.

https://it.vecteezy.com/arte-vettoriale/6600503-mappa-del-medio-oriente

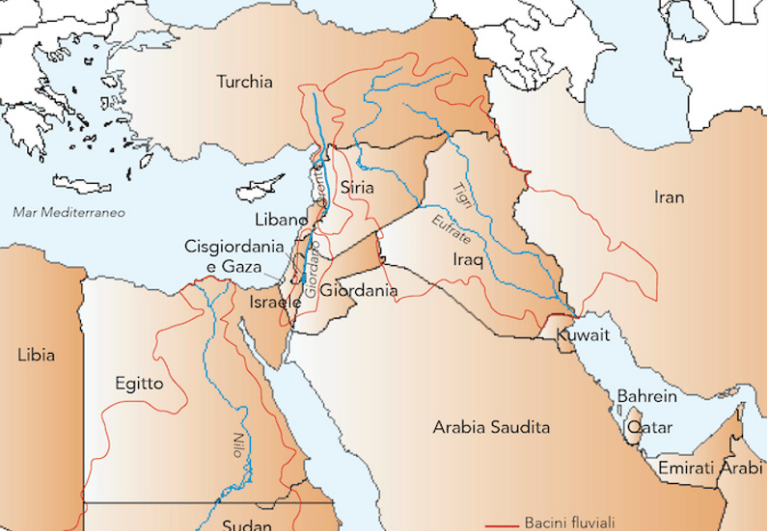

As regards its geographical conformation, as can be seen in figure 2, this vast territory is characterised by the conspicuous presence of mountains, arid plateaus, deserts and Mediterranean environments. It is bathed to the south and south-east by the Indian Ocean, to the south-west by the Red Sea and to the west and north-west by the Mediterranean Sea. In addition, on the border between Israel and Jordan is the Dead Sea, which represents the lowest and saltiest body of water on the entire planet. It is a completely closed water basin that is located 395 metres below sea level, constituting one of the lowest points on Earth[3]. It is called this way because the strong saline component that characterises it does not allow the development of any form of life, except for some bacteria. On the other hand, however, it has a high commercial value for the mineral salts of which it is composed. Today its existence is put to the test due to the reduction in the flow of the rivers that feed it.

Fig. 2: Cartina fisica del Medio Oriente.

https://www.istockphoto.com/it/vettoriale/mappa-fisica-del-medio-oriente-gm613907618-106091567

As far as water resources are concerned, however, it is necessary to underline the problematic condition in which these lands find themselves: in fact, the countries of the Middle East and North Africa are inhabited by approximately 5% of the world's population and possess only 1% of renewable water resources[4]. To this meager presence of water we must add other factors such as the vast desert areas that make up the territory, climate change with the consequent rise in temperatures and the increase in population growth that translates into an imbalance between supply and demand (in this case especially of water).

According to the United Nations, a country is defined as "subject to water stress if it has a per capita availability of between 1,000 and 1,700 m³ of water per year, while between 500 and 1,000 m³ the country is considered to be in water scarcity and under 500 m³ in conditions of absolute scarcity. According to the category of per capita water availability, the Middle East varies from country to country: in fact, if Turkey and Lebanon are slightly above the threshold 7 of water stress, there are also areas such as the Gaza Strip, where water availability is at a level of absolute scarcity”[5].

Despite being a land characterized by a chronic scarcity of water reserves and often complex and insufficient management of resources, this region equally presents important watercourses that are crucial for the water supply, agriculture and economy of individual countries. The most important and above all permanent rivers that we can list are the Tigris and the Euphrates, essential for agriculture, the economy and the production of hydroelectric energy in Iraq, Syria and Turkey. From their confluence originates the Shatt-al-Arab River, a watercourse of about 190 km located in Western Asia that marks the border of Iran and Iraq and then flows into the Persian Gulf[6]. To these latter must be added the Nile, which represents the most important water resource of Egypt as well as one of the main sources of fresh water of the entire area. Another important watercourse, which this article will discuss later, is the Jordan River: it is located in Western Asia and flows through several countries such as Palestine, Jordan, Israel, Lebanon and Syria and is about 350 km long[7].

The majority of these permanent rivers have transnational basins: these are watercourses that flow through several countries, very often causing geopolitical problems that also result in real conflicts. The Nile, for example, essential for Egypt, is shared with nine other African countries while the Tigris-Euphrates-Shatt-al-Arab trio, fundamental for the life of Iraq, is shared with Turkey, Syria and Iran[8]. Indeed, the Jordan basin is divided between Israel, Jordan, the West Bank, Lebanon and Syria. The issue revolving around the Shatt-al-Arab river, which fuelled the conflict between Iraq and Iran for many years, is a long-standing one. In fact, only on 14 August 1990[9] did Iraq accept the re-establishment of the borders as set out in the 1975 agreements, that is, with the recognition by the latter that the river border with Iran ran along the line of the Thalweg of the river itself (according to international law, the Thalweg "is the median line of the navigable channel or the line of maximum flow[10]" with which the borders between different countries are often established). As reported by the Med Or Foundation: "water scarcity is therefore a threat not only for the internal stability of individual countries affected by this problem, but also for the bilateral and multilateral relations of those states crossed by cross-border basins, and which are therefore more inclined to compete for control and access to shared water sources". In addition, the problem of water scarcity that afflicts these areas causes many internal struggles and protests by citizens, which, in other words, means the presence of a general discontent that does not favor the well-being of individual populations.

As regards smaller rivers, however, it must be emphasized that their course varies based on climatic conditions, being periodic rivers.

Fig. 3: I bacini dei principali fiumi del Medio Oriente occupano territori di più Stati, causando complesse questioni geopolitiche.

Acqua in Medio Oriente, le tante insicurezze | Terrasanta.net

The hydro-strategic situation in Israel and Jordan

It is well known that the Middle East is a complex region, even from a hydro-strategic point of view. In fact, this area faces countless water challenges on a daily basis, mainly due to the problem of water scarcity, aggravated by the large presence of desert lands and adverse weather conditions. Therefore, each country adopts different strategies to try to meet this lack: in this article, the solutions proposed by Israel and Jordan will be analyzed.

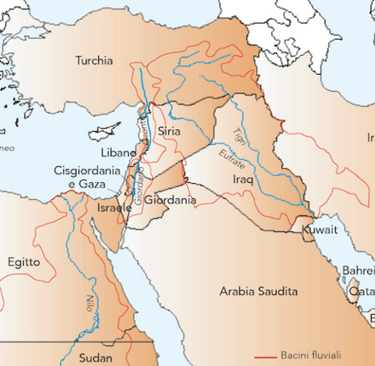

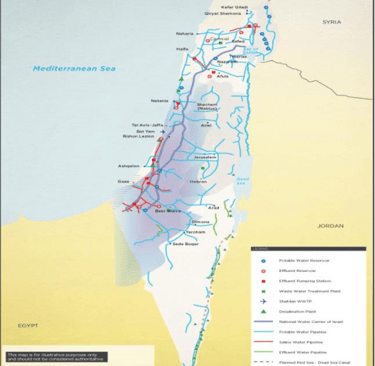

Israel has a territory characterized by 60% desert lands[11], which, added to the problem of the scarcity of rainfall, makes water supply difficult. From the very beginning, therefore, Israel found itself forced to develop advanced plans and technologies to deal with the water shortage. To date, this country holds the record for the development and use of desalination plants, just think that it produces 20% more drinking water than it needs[12]. In fact, according to data from the Israel Export Institute, there are currently around 250 Israeli companies that develop water technologies and equipment, two-thirds of which are startups specializing in the sectors of wastewater treatment, irrigation, desalination plants and water quality detection[13]. As LifeGate reports, it is worth noting that many of these companies participated in the last Water Innovation Technology Summit in 2022, such as: Asterra, specialized in identifying water leaks from underground pipes through the use of satellite data, a company that estimates that almost 64 billion liters of water worldwide are wasted every day due to leaks; Watergen, capable of generating water from the air and Kando, an intelligence company that analyzes data relating to wastewater[14].

The Israeli water issue has also been extensively addressed in another study, also carried out by Ab Aqua – Center for Hydro-strategic Studies, which analyses the Mekorot company, founded in 1937. As the study reports, "the latter is currently Israel's national water company and the country's main agency for water management[15]", in fact, it supplies Tel Aviv with 90% of drinking water and has a high international profile having collaborated with numerous countries around the world in sectors such as desalination, water purification and the construction of water supply plants. It is important to underline that this company played a key role in the construction of the National Water Carrier, a water transport network completed in 1964. It is the largest project in Israel and its main purpose is to transfer water for drinking and agricultural use from the Sea of Galilee (Lake Tiberias) to the central and southern areas of the country[16]. It is about 130 km long and consists of pipes, tunnels, canals and reservoirs that can transport up to 1.7 million m3 of water per day[17]. 80% of the water is used for agriculture but with the growing population growth, more and more water is used for the population.

Fig. 4: Il National Water Carrier di Israele. https://embassies.gov.il/MFA/AboutIsrael/Maps/Pages/Israel-Water-Resources.aspx

Jordan, on the other hand, is in a more critical situation, being among the first countries in the world for water scarcity. In fact, the annual quantity of water consumed by the inhabitants of this region is below the threshold of absolute water scarcity established by the United Nations, that is, as previously mentioned, 500 m³ per person[18]. This is a real emergency, which the lack of rain, the aridity of the soil, the lack of adequate sources of supply and the rise in temperatures only make worse. Another particularly important fact that must be taken into account is the strong urbanization that this land has undergone: the Nakba of 1948 and the proclamation of the State of Israel caused the exodus of more than 750,000 people who were forced to find refuge in neighboring countries, first and foremost Jordan. Adding then the refugees from the Gulf War and other conflicts, the population in this area went from 8 to 11 million inhabitants, triggering a strong demand for water. Over time, the country was forced to resort to the help of neighboring nations to be able to guarantee vital levels of water to its population. In this regard, in fact, the bilateral peace agreement between Jordan and Israel dates back to 1994 based on water cooperation for the benefit of both parties[19]. The agreement included the construction of a canal for the transfer of water from the Red Sea to the Dead Sea, called the Peace Canal.

Fig. 5: Progetto del Canale della Pace.

https://www.researchgate.net/figure/Il-Canale-della-Pace-Mar-Rosso-Mar-Morto_fig3_343361411

However, this important cooperation has waned due to long bureaucratic processes, geopolitical tensions and economic difficulties; therefore, the Peace Canal was never built.

In 2021, Amman, the capital of Jordan, announced that it wanted to start the construction of a national desalination plant in the Gulf of Aqaba, to be completed by 2026[20] and thus making the country self-sufficient. To date, however, 60% of the water supply comes from the exploitation of water contained in aquifers but "renewable aquifers fed by rainfall are constantly decreasing and the waters of Lake Tiberias and the Jordan are almost unusable, especially for irrigation if one takes into account the high salt concentration"[21]. It is therefore evident the need for a timely intervention that can improve the critical conditions in which Jordan finds itself. In this context, a noteworthy event occurred during COP27 held in Egypt where the Memorandum for Project Prosperity was signed. This is a declaration of intent between Jordan and Israel in which the latter undertakes to provide 200 million cubic meters of desalinated water per year to Jordan, which, in exchange, will provide the Jewish state with electricity from a solar plant that will be built on its territory. In fact, the Prosperity project consists of two components: Prosperity Green and Prosperity Blue[22]. The first includes a 600 megawatt (MW) solar photovoltaic plant, integrated with electric storage, which will be built in Jordan to produce clean energy for export to Israel. The second, instead, is a sustainable water desalination program, located in Israel, to export 200 million cubic meters of drinking water to Jordan per year.

The Jordan River at the Center of the Johnston Negotiation (1953-1955)

As previously illustrated, the Jordan River is located in Western Asia and is approximately 350 km long, being a transnational river that flows through several countries such as Palestine, Jordan, Israel, Lebanon and Syria. More precisely, "the course of the Jordan River is divided into two main parts: the Upper Jordan, consisting of three main tributaries: the Dan, the Hasbani and the Banias and reaches Lake Tiberias, 210 meters below sea level; and the Lower Jordan, which extends from Lake Tiberias to the Dead Sea, 395 meters below sea level"[23].

Being a river that flows through several countries, it was necessary to try to establish how much each of them could draw from this resource. The Johnston negotiation therefore had the objective of finding an agreement between the interested parties to ensure a fair and sustainable distribution of the water of the Jordan River and to address the issues related to water security in the region. It arose from a long and complex process, carried out on the basis of a United Nations plan and Israeli and Arab counter-proposals. Furthermore, as reported by Misciali: "the international political framework in which the mission is inserted is rather complex and difficult to define, also because it can be argued that the Johnston negotiation is among the first important episodes of US involvement in the Middle East" [24]. The beginning of this negotiation can be placed in October 1953 and from the very beginning the problem that was evident to the United States was that of finding the theoretical bases on which to base an equal division of the waters.

Fig: 6: Fiume Giordano.

https://it.wikipedia.org/wiki/Valle_del_Giordano

Furthermore, the historically irreconcilable positions of the hypothetical contracting parties further weighed on American mediation: "The Arabs would not have accepted to share such a precious, scarce and highly symbolic resource with a State whose existence they refused to recognize; Israel, for its part, could not negotiate with enemy States to divide a resource that, from the beginning, the Zionist movement had claimed in full"[25]. It came to 4 sessions of negotiations and the implementation of several counter-proposals: the Main Plan; the Arab Plan for Development of the Water Resources in the Jordan Valley, proposed by the Technical Committee of the Arab League as a counter-proposal to the Main Plan and the Plan for the Development and Utilization of the Water Resources of the Jordan and Latini River basins, also called the Cotton Plan, which is the counter-proposal presented by Israel. Furthermore, in the summer of 1955, the partition plan proposed by Johnston was approved by both Jordan and Israel, but despite this, an agreement was never reached. Let us remember that "Jordan is a small, arid country, which hosts thousands of refugees, no less demanding than the rest of the population as regards the need for water. These two elements, the presence of thousands of refugees and the fact that 80% of the country is desert, make it clear that, faced with the hypothesis of an equitable division of water and the possibility of implementing a development project, Jordan was the country that had the most to gain from a successful negotiation"[26]. The merit of this negotiation, however, was that it succeeded in bringing the different positions of the individual countries as close as possible, to the point of being able to find compromises and a willingness to dialogue and leaving, momentarily, behind the various geopolitical tensions. To date, the Jordan basin area is shared by five countries: Jordan for 40%, Syria for 37%, Israel 10%, Palestine 9% and Lebanon 4%[27].

Conclusion

It is therefore evident that these lands, in addition to having to deal with important geopolitical issues, must also deal with water scarcity problems on a daily basis, which, very often, are the cause of tensions between different countries. The entire Middle East region is characterized by a complex hydro-strategic situation accentuated by the challenges posed by a predominantly desert environment.

In this study, in particular, attention was paid to how, despite the serious water scarcity in which these lands live, some countries have managed to become self-sufficient, even managing to produce more drinking water than necessary, as in the case of Israel. The latter, in fact, has developed cutting-edge technologies for the desalination of sea water, wastewater recycling and drip irrigation. Jordan was then discussed, as one of the driest countries in the world and with mostly underground water resources, it has recently begun to invest in addressing its water scarcity, with the aim of becoming self-sufficient like Israel.

Despite these efforts, water management remains a critical issue for both countries, with significant challenges still to be addressed. Rising regional tensions and political conflicts complicate efforts to share and sustainably manage water resources, while socioeconomic disparities within countries can lead to inequalities in access to water.

Bibliografia

Le risorse idriche in Medio Oriente, Contributi di Istituti di ricerca specializzati. Senato della Repubblica, a cura di Simone Nella del Centro Studi Internazionali (Ce.S.I.) n. 63, Dicembre 2006.

Misciali, Paola. I Bisogni Idrici Nella Crisi Medio-Orientale. Il Negoziato Johnston Sul Bacino Del Giordano (1953-1955), Rivista Di Studi Politici Internazionali, vol. 68, no. 4 (272), 2001, pp. 550–68.

RONZITTI, Natalino, Diritto Internazionale, VI edizione, G. Giappichelli Editore, Torino, 2019.

Sitografia

https://www.treccani.it/enciclopedia/medio-oriente/, 27 marzo 2024, 17:03.

Medio Oriente in “Enciclopedia dei ragazzi” – Treccani – Treccani, 3 aprile 2024, 18:17.

Il “modello-Israele” per l’acqua, tra grandi innovazioni e gravi violazioni (lifegate.it), 5 aprile 2024, 10:51.

L’innovazione tecnologica israeliana al servizio dell’efficienza idrica. Un esempio da seguire – Abaqua, 5 aprile 2024, 12:18.

https://www.catalfamo.edu.it/wp-content/uploads/2020/03/IL-MEDIO-ORIENTE.pdf, 5 aprile 2024, 18:32.

GIORDANO in “Enciclopedia Italiana” – Treccani – Treccani, 6 aprile 2024, 17:08.

Acqua in Medio Oriente, le tante insicurezze | Terrasanta.net, 6 aprile 2024, 17:23.

Shatt al Arab nell’Enciclopedia Treccani – Treccani – Treccani, 6 aprile 2024, 19:21.

National Water Carrier Begins Pumping | CIE (israeled.org), 9 aprile 2024, 12:10.

Giordania, crisi idrica tra sfruttamento e disuguglianze – Non Dalla Guerra, 9 aprile 2024, 12:59.

Scarsità idrica in Medio Oriente: quali limiti alla… | Med-Or, 9 aprile 2024, 16:04.

Emirati Arabi Uniti, Giordania e Israele: protocollo d’intesa per desalinizzazione sostenibile dell’acqua in vista di COP28 | Agenzia di stampa Emirates (wam.ae), 9 aprile 2024, 16:53.

https://lospiegone.com/2020/05/02/loro-blu-del-medio-oriente-il-bacino-del-giordano/#:~:text=L’area%20del%20bacino%20del,l’asse%20principale%20del%20bacino, 9 aprile 2024, 18:33.

______________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________

[1] https://www.treccani.it/enciclopedia/medio-oriente_(Enciclopedia-dei-ragazzi)/, 3 aprile 2024.

[2] https://www.treccani.it/enciclopedia/medio-oriente/, 27 marzo 2024.

[3] https://www.catalfamo.edu.it/wp-content/uploads/2020/03/IL-MEDIO-ORIENTE.pdf, 5 aprile 2024.

[4] Acqua in Medio Oriente, le tante insicurezze | Terrasanta.net, 6 aprile 2024.

[5] Le risorse idriche in Medio Oriente, Contributi di Istituti di ricerca specializzati. Senato della Repubblica, a cura di Simone Nella del Centro Studi Internazionali (Ce.S.I.) n. 63. Dicembre 2006. Pag. 7-8.

[6] Acqua in Medio Oriente, le tante insicurezze | Terrasanta.net, 6 aprile 2024.

[7] GIORDANO in “Enciclopedia Italiana” – Treccani – Treccani, 6 aprile 2024.

[8] Acqua in Medio Oriente, le tante insicurezze | Terrasanta.net, 6 aprile 2024.

[9] Shatt al Arab nell’Enciclopedia Treccani – Treccani – Treccani, 6 aprile 2024.

[10] Natalino Ronzitti, Diritto Internazionale, VI edizione, Torino, G. Giappichelli Editore, 2019, p.85.

[11] Il “modello-Israele” per l’acqua, tra grandi innovazioni e gravi violazioni (lifegate.it), 5 aprile 2024.

[12] Il “modello-Israele” per l’acqua, tra grandi innovazioni e gravi violazioni (lifegate.it), 5 aprile 2024.

[13] Il “modello-Israele” per l’acqua, tra grandi innovazioni e gravi violazioni (lifegate.it), 5 aprile 2024.

[14] Il “modello-Israele” per l’acqua, tra grandi innovazioni e gravi violazioni (lifegate.it), 5 aprile 2024.

[15] L’innovazione tecnologica israeliana al servizio dell’efficienza idrica. Un esempio da seguire – Ab Aqua, 5 aprile 2024.

[16] National Water Carrier Begins Pumping | CIE (israeled.org), 9 aprile 2024.

[17] National Water Carrier Begins Pumping | CIE (israeled.org), 9 aprile 2024.

[18] Giordania, crisi idrica tra sfruttamento e disuguaglianze – Non Dalla Guerra, 9 aprile 2024.

[19] Scarsità idrica in Medio Oriente: quali limiti alla… | Med-Or, 9 aprile 2024.

[20] Scarsità idrica in Medio Oriente: quali limiti alla… | Med-Or, 9 aprile 2024.

[21] Le risorse idriche in Medio Oriente, Contributi di Istituti di ricerca specializzati. Senato della Repubblica, a cura di Simone Nella del Centro Studi Internazionali (Ce.S.I.) n. 63. Dicembre 2006. Pag.10.

[22] Emirati Arabi Uniti, Giordania e Israele: protocollo d’intesa per desalinizzazione sostenibile dell’acqua in vista di COP28 | Agenzia di stampa Emirates (wam.ae), 9 aprile 2024.

[23] Le risorse idriche in Medio Oriente, Contributi di Istituti di ricerca specializzati. Senato della Repubblica, a cura di Simone Nella del Centro Studi Internazionali (Ce.S.I.) n. 63. Dicembre 2006. Pag.10.

[24] Misciali, Paola. I Bisogni Idrici Nella Crisi Medio-Orientale. Il Negoziato Johnston Sul Bacino Del Giordano (1953-1955), Rivista Di Studi Politici Internazionali, vol. 68, no. 4 (272), 2001, pp. 550-551.

[25] Misciali, Paola. I Bisogni Idrici Nella Crisi Medio-Orientale. Il Negoziato Johnston Sul Bacino Del Giordano (1953-1955), Rivista Di Studi Politici Internazionali, vol. 68, no. 4 (272), 2001, pp. 554.

[26] Misciali, Paola. I Bisogni Idrici Nella Crisi Medio-Orientale. Il Negoziato Johnston Sul Bacino Del Giordano (1953-1955), Rivista Di Studi Politici Internazionali, vol. 68, no. 4 (272), 2001, pp. 555-556.

[27]https://lospiegone.com/2020/05/02/loro-blu-del-medio-oriente-il-bacino-del-giordano/#:~:text=L’area%20del%20bacino%20del,l’asse%20principale%20del%20bacino, 9 aprile 2024.

National Strategies of Jordan and Israel in Addressing Water Crises

Ludovica Saccone - May 9, 2024

Abaqua

Via Cassia, 615

00189 Roma (RM)

© 2024. All rights reserved.

Codice Fiscale: 96584590580