The Fragility of Water Sharing Relations Between India and Pakistan

Isabella De Baptistis - June 22, 2024

L’immagine di copertina di questo paper è stata presa dal sito di The Diplomat, consultabile al seguente link: https://thediplomat.com/2023/04/troubled-waters-india-pakistan-and-the-indus-water-treaty-2-0/

The hydro-strategic rivalries involving India and Pakistan are not easily understood without retracing one of the most salient moments of their common history and without also taking into consideration the current international context and the aspirations/priorities of both nations. In 1947, the division of the colony of British India into two separate and independent states, India and Pakistan, was sanctioned. Until that time, during British rule, the Hindu, Sikh and Muslim communities had coexisted in the Indian subcontinent for hundreds of years, with limited tensions.

The creation of the dual state, on religious and confessional grounds, granted Indian Muslims (30% of the population) their own independent nation, in order to avoid possible oppression by the Hindu majority. The birth of the two state entities was characterized by enormous tensions and terrible violence, which caused the mass migration of 12-15 million people.

Since their independence, India and Pakistan have already faced each other in three wars (1965, 1971 and 1999), as well as in shorter-term conflicts and border incidents. The object of these clashes has been and still is the region of Kashmir, with a Muslim majority (the only one in the Indian subcontinent), belonging to Indian territory and disputed by the two countries since independence in 1947. Kashmir, today divided into three provinces, two of which are Pakistani (Gilgit Baltistan and Azad Kashmir) and one of India (Jammu and Kashmir), is a rich and strategic area in terms of minerals and water.

While the hydrography of the region has ensured India a certain security in water supplies, thanks to the numerous rivers that cross it, Pakistan, on the contrary, does not enjoy the same advantage. The Pakistani region depends entirely on the Indus River, the only large river basin in the area capable of supporting the development of the nation.

Based on this strategic difference, for over half a century, control of river resources has been a source of interstate rivalry and tension between India and Pakistan. The Indus River flows mainly between India (39%) and Pakistan (47%), with small sections in Tibet and eastern Afghanistan (FAO, 2011a) [1].

During the formation of the two states, the boundary lines between India and Pakistan were drawn following those naturally traced by the so-called “Indus watershed” (Gardner, 2019) [2].

The placement of these lines has benefited India in managing the dams that regulate the flow of water to Pakistan. The physical border between the two states cuts off many of the river’s tributaries, creating a key water structure, under Indian administration, that becomes a source of tension between the two countries. The Indian government’s extraordinary availability of water resources and infrastructure, such as dams and hydroelectric plants, represent not only a precious source of energy for the country’s economy, but also a constant threat to the fragile geopolitical balances of the region.

Fears of future water shortages, arising from state management of available resources and divisive political narratives, generate recurrent diplomatic crises between the two states. On the one hand, in India, the violent actions of the Islamic terrorist cell (Jaish-e-Mohammad), considered to be affiliated with Pakistan, are often exploited to justify a cooling of bilateral relations and even to threaten to reduce Pakistan's water supply (Al Jazeera, 2019; Roy, 2019) [3]. On the other hand, Pakistani nationalist media accuse India of promoting flooding in the country, caused by inadequate management of water resources, fundamentally based on a principle of self-referentiality.

The Indus Waters Treaty: Legal Guarantor of Peace

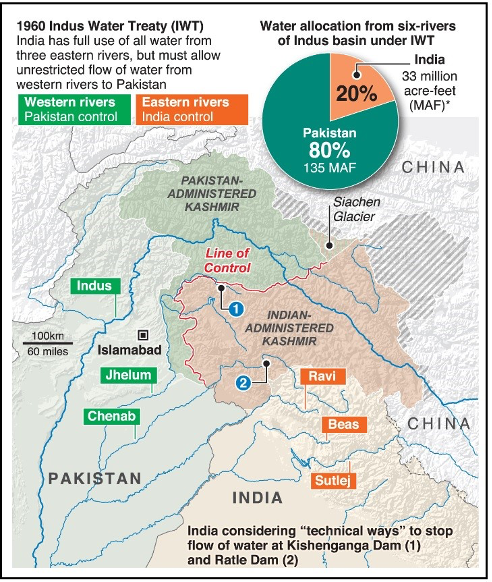

Water issues in the Indus basin are mainly regulated by the Indus Waters Treaty (IWT, 1960). With the mediation of the World Bank, the Treaty defined the principles of interstate sharing of Indus water to avoid water conflicts between India and Pakistan. The World Bank played a key role in mediating the negotiations, which arose following an episode in 1948, when India cut off water supplies to many villages in Pakistan. The international organization also provided financial support to both Pakistan and India in building water storage and transportation facilities.

Fig. 1: Allocazione delle risorse idriche tra India e Pakistan

https://climate-diplomacy.org/case-studies/water-conflict-and-cooperation-between-india-and-pakistan

The Treaty stipulates in 12 articles that control over the three eastern tributaries of the Indus River (Ravi, Sutlej and Beas), which then flow into Pakistan, is entrusted to India, while the three western tributaries – Indus, Jhelum and Chenab – are under the management of Pakistan. The functioning of the Treaty is based on the biannual meeting of the Water Commissioners of Pakistan and India who organize technical visits to the work sites on the sources of the rivers. The Treaty establishes a mechanism for cooperation and exchange of information between the two countries regarding the use of their river sources.

Although the regulatory framework governing the distribution of water between the two states has been generally accepted by both parties, the Treaty has been subject to increasing disputes, due to the numerous Indian hydroelectric projects, the construction of dams and the consequent alteration of the flow of water to Pakistan. The country questions both the assignment of control over the Indus tributaries and the concessions that have allowed India to legally build infrastructure that would jeopardize Pakistan's water security.

At the same time, Pakistan has also turned to its ally China, which supports Pakistan's independent sovereignty and territorial integrity, in search of greater economic influence in the region through the implementation of economic projects (China-Pakistan Economic Corridor, CPEC).

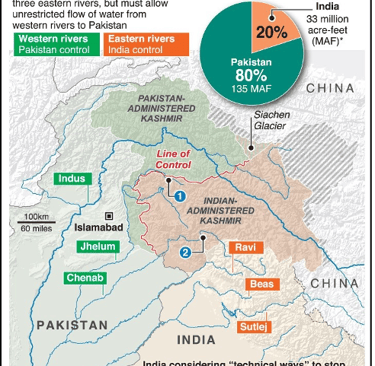

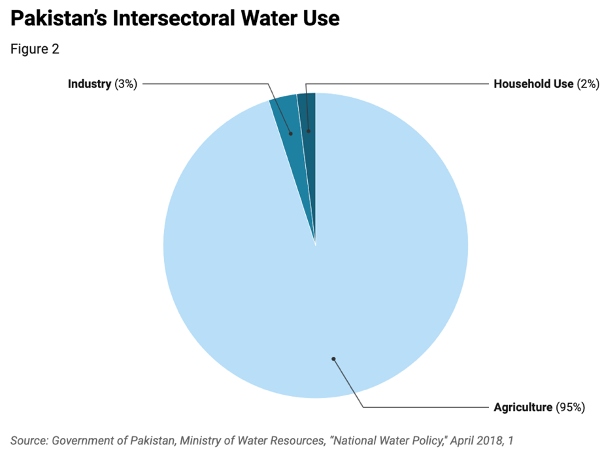

Fig. 2: Risorse idriche in Pakistan e domanda delle famiglie

https://www.stimson.org/2023/pakistans-political-economy-perpetuates-its-water-crisis/

Water as a Cause of Tension

The shared Indus Basin is the second most used aquifer in the world. However, over-extractions pose long-term risks to the water availability of the entire basin. In the Indus region, it may seem paradoxical that Pakistan is one of the most water-stressed countries in the world. Despite Pakistan having enough water to meet the needs of its population, millions of Pakistanis still lack access to water (Figure 1).

According to the World Health Organization (WHO), a person needs to have access to between 50 and 100 liters of water per day to live a dignified life [4]. Considering Pakistan’s population, the country would need between 3.5 and 7 million acres (MAF) of water annually to meet its collective domestic demand [5].

Despite varying estimates, Pakistan's collective annual water availability amounts to approximately 193 MAF [6]. As anticipated, unlike India, Pakistan also depends almost exclusively on the Indus: approximately 90% of Pakistan's food and 65% of its employment come from agriculture and livestock. In addition, the southern areas of the country are particularly vulnerable to water supplies from the basin, exposing local communities to the risk of social tensions.

Fig. 3: Uso intersettoriale dell’acqua in Pakistan

https://www.stimson.org/2023/pakistans-political-economy-perpetuates-its-water-crisis/

In addition to poor management of water resources, the consequences of climate change contribute to the emergence of situations of water ‘stress’. In this regard, it is expected that the Himalayan glaciers, which feed the Indus basin, will further decrease in the coming years. This reduction will cause a temporary increase in water flow, but will impoverish, in the long term, the recharge of aquifers, thus reducing available water resources [7]. In fact, it is estimated that the flow of the Indus will decrease by 8% by 2050. At the same time, it is assumed that the pace and intensity of rainfall during the monsoons will become increasingly irregular, increasing the risk of flooding.

Such a scenario would suggest an increase in political tensions between the two superpowers with respect to the distribution of water and the management of flows. Over the years, water has already been an instrument of tension between the two countries. Indeed, Pakistan has repeatedly appealed to international institutions over alleged Indian violations of the Treaty in response to India’s various dam-building projects that would have altered the flow of water downstream.

The first occasion was when Pakistan approached the World Bank with a request to appoint a neutral expert after raising concerns over India’s construction of the Baglihar Dam on the Jhelum River. Pakistan argued that these hydroelectric projects would have given Indian engineers more control over the flow of the river than the Treaty allows. The neutral expert, however, approved India’s construction plans in 2007 [8].

Pakistan later appealed to the World Bank again, seeking an arbitration panel to rule on India’s construction of the Kishanganga Dam on a tributary of the Jhelum River. The 2013 ruling by the Permanent Court of Arbitration in The Hague granted India the right to terminate the project, although it did not completely side with either country [9].

Fig. 4: Diga idroelettrica di Baglihar

Fig. 5: Costruzione della diga di Kishanganga

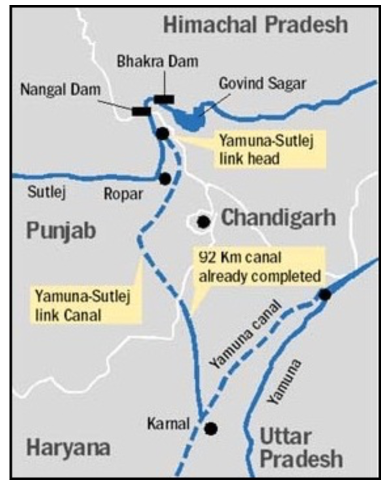

Tensions between India and Pakistan flared up again in 2016 with a terrorist attack in the city of Uri in the Kashmir region. On this occasion, India cancelled its participation in the meeting of the Permanent Indus Commission (PIC) [10] and, at the same time, called a meeting to amend or annul the Indus Water Treaty. Similarly, India accelerated the development of three water projects including the construction of the Shahpur-Kandi dam and the UJH in Jammu and Kashmir and a second Sutlej-Beas link in Punjab [11].

In 2016, Pakistan consulted the World Bank for the appointment of another arbitration tribunal to rule on the construction of the Indian Ratle dam on the Chenab river; in return, India pushed for the appointment of a neutral expert. Much to the chagrin of Indian officials, the World Bank decided to launch both processes simultaneously in 2017, appointing key experts in October 2022.

Fig. 6: Progetto di collegamento Sutlej-Beas

Indian officials have threatened to ignore any opinion of the arbitral tribunal. The vulnerability of the India-Pakistan relationship on water issues was further highlighted in 2019, following a terrorist attack, claimed by the Pakistani militia Jaish-e Mohammad, in Pulwama (Indian-administered Kashmir), in which 46 members of the Indian paramilitary police lost their lives. The Indian political response came through the words of the then Minister of Water Resources, Nitin Gadkari, who threatened to cut off the flow of water to Pakistan, terminating the Indus Water Treaty [12].

However, the wording of the Treaty does not provide for either country to unilaterally withdraw from the pact. Article XII of the Treaty provides that: “The provisions of this Treaty, as amended under the provisions of paragraph (3), shall continue in force until terminated by a treaty duly ratified and concluded for that purpose between the two Governments”. On 25 January 2023, India, for the first time in the history of the pact, advanced the request to amend the Treaty through the Permanent Indus Commission. Specifically, New Delhi has expressly asked Pakistan to renegotiate the terms of the dispute resolution. This request could be used by India as a bargaining chip in an attempt to perpetuate pressure on Pakistan on other political issues.

Conclusions

The analysis of water management between India and Pakistan highlights the need for modernization and adaptation of the Indus Water Treaty to climatic circumstances and environmental policies. The agreement, in fact, does not consider the effects of climate change on overall water availability and its distribution in the region. On the contrary, it would be desirable, in the current context, for the agreement to provide for preventive measures for natural disasters, which are increasingly frequent and intense in this territory.

Furthermore, the Treaty does not establish a limit on the amount of dams that New Delhi could build in the Indus basin, and lacks indications, moreover, on the amount of water distribution between the two States, thus granting an expedient for potential Indian overexploitation. The widespread diffusion of Indian dams and hydroelectric plants represents, in fact, not only an advantageous source of energy, but also a permanent threat to the fragile regional geopolitical balances.

The Treaty's regulatory shortcomings therefore relaunch the need to discuss and approve international laws on the governance of transboundary rivers and lakes, also in light of the political and social tensions between the two States that weaken the effectiveness and operation of the agreement itself, also putting cooperation relations at risk.

As retraced in this report, the ancient rivalries between the two countries, mainly due to the ownership of the territory of Kashmir, have changed over time into a dispute over water resources. In Pakistan, the water issue arouses strong and constant participation that fuels anti-Indian propaganda. In India, however, the presence of important water infrastructures takes on various strategic values: it guarantees running water to Indian families, ensures irrigation of cultivated fields, provides energy and contributes to the modernization and technological development of the nation. Jawaharlal Nehru, leader of Indian independence, presented, three years after the signing of the Treaty (1963), the Bhakhra dam on the Satluj river, the first large Indian hydroelectric plant, as "a temple of modern India" [13].

Today more than ever, India has understood the necessity and the strategic return of the political-economic management of water. This awareness responds to various Indian strategic needs: it guarantees internal development and addresses the national difficulty of ensuring equitable and sufficient access to water resources to its large population, but, at the same time, it strengthens the Indian image at the international level as a mature and avant-garde nation, at a historical moment in which India seeks an increasingly decisive geopolitical role in world dynamics.

On the occasion of the United Nations Water Conference in 2023, Minister Gajendra Singh Shekhawat announced that India plans to invest more than 240 billion dollars [14] in the water sector. India is also working, in collaboration with private individuals, start-ups and water users' associations, to implement the world's largest dam rehabilitation program, to build water storage infrastructure, which is essential for climate resilience.

India's growth prospects in the water sector, combined with a context of crisis in multilateralism and a lack of international legislation for trans-boundary management of water resources, pushes for the strengthening of bilateral cooperation tools to achieve a new model of basin management, which can be summarized in the concept of "Hindustan" [15]. This neologism encourages considering and governing the Indus basin as a single, integrated and shared resource, to avoid hydro-diplomatic fractures that could lead to a wider deterioration of bilateral relations, putting at risk the hard-won ceasefire achieved in Kashmir.

___________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________

[1] Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations, “AQUASTAT, FAO’s Global Information System on Water and Agriculture”, 2011: https://www.fao.org/aquastat/en/countries-and-basins/transboundary-river-basins/indus.

[2] Climate Diplomacy, “Water conflict and cooperation between India and Pakistan”: https://climate-diplomacy.org/case-studies/water-conflict-and-cooperation-between-india-and-pakistan.

[3] Aljazeera, “India reiterates plan to stop sharing water with Pakistan”, 2019: https://www.aljazeera.com/news/2019/2/21/india-reiterates-plan-to-stop-sharing-water-with-pakistan.

[4] United Nations, Resolution A/RES/64/292, “The Human Right to Water and Sanitation”, 2010: https://www.un.org/waterforlifedecade/pdf/human_right_to_water_and_sanitation_media_brief.pdf.

[5] Uzair Sattar, “Pakistan’s Political Economy perpetuates its Water Crisis”, STIMSON, 2023: https://www.stimson.org/2023/pakistans-political-economy-perpetuates-its-water-crisis/.

[6] U.S. Institute of Peace, “Understanding Pakistan’s Water-Security Nexus”, 2013: https://www.usip.org/sites/default/files/PW88_Understanding-Pakistan’s-Water-Security-Nexus.pdf

[7] Dhanasree Jayaram, “Why India and Pakistan need to review the Indus Waters Treaty”, Climate Diplomacy, 2016: https://climate-diplomacy.org/magazine/cooperation/why-india-and-pakistan-need-review-indus-waters-treaty

[8] Daniel Haines, “India and Pakistan are playing a dangerous game in the Indus Basin”, United States Institute of Peace, 2023: https://www.usip.org/publications/2023/02/india-and-pakistan-are-playing-dangerous-game-indus-basin.

[9] Idem.

[10] Commissione bilaterale composta da funzionari dell’India e del Pakistan, istituita dal Trattato.

[11] Debayan Roy, “Can India unilaterally revoke Indus Water Treaty with Pakistan”, News18, 2022: https://www.news18.com/news/india/can-india-revoke-indus-water-treaty-unilaterally-news18-explainer-2045325.html

[12] Aljazeera, “India reiterates plan to stop sharing water with Pakistan”, 2019: https://www.aljazeera.com/news/2019/2/21/india-reiterates-plan-to-stop-sharing-water-with-pakistan

[13] Adriano Marzi, “L’acqua contesa tra Pakistan e India”, Nuova ecologia, 2019: https://www.lanuovaecologia.it/acqua-contesa-tra-pakistan-e-india/.

[14] Smart Water Magazine, “India to invest over $240 billion in water sector”, 2023: https://smartwatermagazine.com/news/smart-water-magazine/india-invest-over-240-billion-water-sector.

[15] Institute for Water, Environment and Health, dell’Università delle Nazioni Unite (UNU-INWEH) ha pubblicato, su Springer, il report “Imagining Industan”.

Abaqua

Via Cassia, 615

00189 Roma (RM)

© 2024. All rights reserved.

Codice Fiscale: 96584590580