Iran's Water Bankruptcy

Pietro Secchi - September 25, 2025

Introduction

While international attention has long been focused on Iran's nuclear program, a more subtle, yet potentially catastrophic, crisis is escalating within the Islamic Republic: the water crisis. This issue is no longer a peripheral concern but one of the most significant and underestimated challenges of the present era, with the potential to generate severe socioeconomic and geopolitical repercussions that extend far beyond national borders.

Historically, Iran has showcased remarkable adaptability to its arid environment through ingenious water management systems, such as the ancient qanat (or kariz)—a feat of underground hydraulic engineering—and the renowned windmills. However, the nation now stands at the precipice of what experts have termed "water bankruptcy," a condition where the rate of water extraction consistently surpasses the natural rate of resource replenishment.

Evidence of the Crisis

The manifestations of Iran's water crisis are now ubiquitous and profoundly impactful across the nation. From the severely depleted reservoirs surrounding Tehran to the arid expanses of Khuzestan, water scarcity poses a direct threat to urban centers, agriculture, and water-intensive industries.

A particularly salient example is the Zayanderud River, whose name translates to "the one who gives life." This river, a vital artery for the province of Isfahan, has been reduced to a dry riverbed for much of the year for decades, permanently disrupting the livelihoods of millions and crippling agricultural operations. Equally alarming is the fate of Lake Urmia in the northwest. Once the sixth-largest saltwater lake in the world, it has been decimated by recurrent droughts, intensive agricultural abstraction, and diversions of various kinds. Further east, the Hamoun wetlands have experienced a complete ecological collapse over the past two decades, leading to the disappearance of entire ecosystems and fish populations.

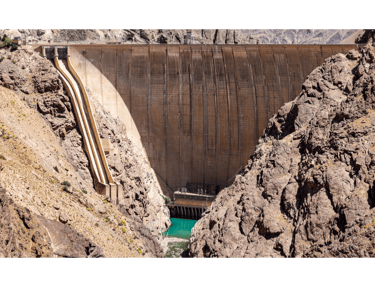

The cumulative data paints a stark picture of hydrological decline. Over the last two decades, Iran has depleted its water reserves by more than 200 cubic kilometers, which represents approximately 25–30% of its historical endowment. Many dam-related reservoirs now hold only 6–13% of their original capacity, with numerous others completely dry. This is often the result of underutilized or mismanaged infrastructure that is simply unable to cope with prolonged drought conditions.

The crisis has now directly impacted major urban centers, most notably Tehran. With a population of nearly ten million, the capital is on the verge of what is known as "day zero"—a point at which municipal water supplies fail. Reservoirs that supply the city retain barely 20% of their capacity, necessitating extraordinary measures such as rationing, the use of temporary storage tanks, and water transport by truck. In a recent statement, President Pezeshkian warned that without drastic reductions in consumption, dam water could be exhausted by autumn. A few days later, the government was compelled to declare a national day of closure due to severe water and electricity shortages, as temperatures in the capital soared above 40°C. Within this context, extreme scenarios—including the potential forced relocation of urban populations—are now under serious consideration, underscoring that the water crisis is no longer a latent threat but a direct challenge to national security.

Fig. 1: The Amir Kabir Dam in the Alborz mountain range, northern Iran. https://edition.cnn.com/2025/07/31/climate/tehran-iran-water-crisis-day-zero

Causes of the Crisis

The roots of Iran’s water crisis are not attributable to a single factor but rather a complex interplay of natural, demographic, and political elements, which together have created a situation with potentially catastrophic humanitarian consequences.

Iran's initial vulnerability stems from its natural aridity. With an average annual rainfall of just 250 millimeters—less than one-third of the global average—the nation is inherently one of the most water-stressed in the world. This natural disadvantage is compounded by significant demographic pressure. Over the past fifty years, the population has doubled to 90 million, with a high concentration in major metropolitan areas like Tehran, Mashhad, and Isfahan. This rapid and unplanned urbanization has strained water management and distribution systems, placing an immense burden on often outdated or poorly maintained infrastructure. Furthermore, climate change intensifies these issues, with rising temperatures and increased precipitation variability leading to higher rates of evaporation from surface reservoirs and prolonged drought periods. For example, in 2025, at the peak of the fifth consecutive year of drought, annual rainfall plummeted to approximately 150 millimeters, reducing Iran’s water resilience by over 40% compared to historical averages.

However, focusing solely on natural and demographic factors provides only a partial understanding of the crisis. The consensus among both Iranian and international experts is that consumption patterns are the primary drivers, with the agricultural sector playing a dominant role. This sector consumes over 90% of available water resources while contributing only 10–15% to the national GDP. The low efficiency of this sector is exacerbated by political constraints. International sanctions have limited access to modern irrigation technologies, perpetuating highly wasteful, outdated practices. Concurrently, state policy has prioritized food self-sufficiency as a pillar of the “resistance economy,” incentivizing the cultivation of water-intensive crops—such as wheat, pistachios, and sugarcane—which often have low added value relative to the volume of water they consume. The influence of the bonyad—powerful quasi-state foundations with ties to the Supreme Leader—is also notable, as they have promoted large-scale agricultural projects that consume vast quantities of water and reinforce a system of waste and privilege.

To support this production model, authorities have relied on two primary instruments: dam construction and groundwater exploitation. Iran is among the countries that have built the highest number of dams in recent decades, which were presented as modern solutions for rebalancing water distribution between regions. Yet, the outcomes have been highly controversial, leading to the displacement of communities, the draining of wetlands and lakes, ecological destruction, and water pollution. As previously noted, many of these reservoirs remain empty or nearly empty, fueling public skepticism about their utility, while corruption and mismanagement have often transformed these infrastructures into tools of patronage rather than effective responses to the crisis.

The most severe collapse, however, has occurred beneath the surface. The uncontrolled expansion of both legal and illegal wells has led to the over-extraction of water across 77% of the country, causing a staggering decline in aquifers by approximately 28 centimeters per year. The consequences of this over-abstraction are severe and widespread, including soil salinization, widespread land subsidence, irreversible damage to infrastructure, and increased vulnerability for rural communities.

This internal scenario is further complicated by a geopolitical dimension concerning the management of transboundary aquifers. While cooperation with neighboring countries has thus far prevented significant conflicts, the depletion of shared groundwater reserves risks escalating tensions, particularly along the border with Afghanistan, with potential implications for the stability of the wider region.

Internal Socio-Political Implications

Water scarcity in Iran has evolved beyond a mere environmental concern to become a direct threat to the country's overall stability. In an arid context where access to water is a fundamental condition for survival, the state's capacity to effectively manage this resource has become a key indicator of its governance efficiency. The inability to secure this vital resource fuels widespread public discontent and progressively erodes the credibility of governing institutions.

The economic ramifications of the water crisis are both tangible and pervasive. Agro-food supply chains—from wheat to fruits and vegetables—are experiencing structural declines in productivity, with direct impacts on national food security and cascading effects on employment and income in rural communities. In strategic provinces like Khuzestan and Fars, agricultural productivity has dropped by an estimated 18% in recent years, while roughly one-quarter of farmers have lost their livelihoods, compelling many families to migrate to urban centers. As early as 2014, Issa Kalantari, the former head of the Department of Environment, warned that water resources allocated to agriculture would become insufficient within fifteen years without a change in consumption patterns. Today, that forecast is materializing, threatening not only the economy but also the very social cohesion of the nation.

It is therefore unsurprising that "water protests" have become a recurrent feature of the Iranian landscape. From Khuzestan to Isfahan and from Yazd to Sistan-Baluchistan, agricultural strikes, road blockades, and demonstrations have highlighted a growing rift between the population and the authorities. What began as localized disputes over water management has evolved into broader grievances, encompassing urban communities affected by rationing and supply interruptions, as well as a widespread sense of injustice. Areas such as Khuzestan, with an Arab majority, and Sistan-Baluchistan, home to Baluchi communities already at odds with the central government, are particularly sensitive. In these regions, water scarcity risks intersecting with identity-based claims, creating a potential political fault line capable of amplifying tensions on a national scale.

The pressure of water scarcity is accelerating an unprecedented flow of internal migration. Many rural communities, whose livelihoods have been stripped away by desertification and the depletion of aquifers, are forced to relocate to the north or to urban peripheries, effectively transforming their populations into internal climate refugees. According to some projections, millions of Iranians could be involved in such population movements by 2050. This forced migration could have disruptive consequences, including increased overcrowding, heightened competition for housing and services, social marginalization, and the potential for new local conflicts.

Fig. 2: Iran faces water crisis https://www.abc.net.au/news/2025-08-02/iran-and-middle-east-record-heat-drought-wildfires/105590076

Proposals

Addressing Iran’s water crisis requires an approach that extends well beyond emergency measures and the construction of new infrastructure. Instead, it necessitates a systemic transformation capable of integrating governance, economic, social, and ecological dimensions. Historical experience demonstrates that survival in Iran's arid environment was made possible by technical ingenuity and communal cooperation. However, the current depth of the crisis demands a qualitative leap, one that structurally redefines the relationship between society, politics, and the environment.

1. Governance Reform: A crucial first step is to reform the country's water governance. Centralized and at times nontransparent management of water resources has led to inefficiencies, unequal distribution, and a pervasive lack of trust. A structural reform should involve creating independent basin authorities, equipped with transparent monitoring tools and decision-making autonomy. The benefits would be manifold: enabling the control of illegal water abstraction, ensuring integrated territorial planning, and rebuilding trust between citizens and institutions. However, such reforms would inevitably face resistance from the bonyad and other actors who benefit from the current disorder; without institutional rebalancing, technical measures alone risk remaining ineffective.

2. Reforming the Agricultural Sector: Agriculture constitutes a second priority, not only due to its disproportionate water consumption but also because of its profound social and political implications. The widespread adoption of efficient irrigation systems—such as drip or tape irrigation, which have been successfully implemented in arid countries like Israel and Jordan—could significantly reduce waste, provided it is accompanied by training programs and facilitated access to modern technology. Yet, this step alone is insufficient. Rather than pursuing the unrealistic goal of cereal self-sufficiency, Iran should adopt a more flexible concept of food security. This would involve gradually phasing out water-intensive crops in the most critical basins, promoting drought-tolerant or less demanding varieties, and resorting to targeted imports for high-water-footprint goods. This strategy has already been applied in countries with similar climatic conditions, such as Saudi Arabia, with immediate effects in alleviating pressure on aquifers. However, this agricultural conversion carries significant social risks, as it could disproportionately affect already vulnerable rural communities. Therefore, any such transformation must be accompanied by incentive packages, insurance schemes, and income support programs to ensure that farmers are active participants in the transition, rather than its victims.

3. Managing Demand and Infrastructure: Another crucial front is demand management. On one hand, a gradual reform of the water pricing system is essential. Decades of water and energy subsidies have encouraged waste and over-extraction. The introduction of increasing block tariffs—with low costs for essential consumption and higher costs for marginal uses—would help rebalance demand and promote more responsible use. On the other hand, the urban and industrial sectors must also be addressed. Reducing losses in water distribution networks, which are currently at unsustainable levels, and upgrading treatment facilities to promote wastewater reuse are measures capable of freeing up precious volumes and reducing pressure on groundwater. While technologically and economically demanding, and constrained by international sanctions, these interventions are essential to provide a "safety valve" in urban contexts exposed to the risk of "Day Zero.”

4. Ecological Dimension: Beyond the economic and infrastructural dimensions, the ecological aspect must also be addressed. Iran’s water crisis is not only quantitative but also qualitative: desertification, salinization, and land subsidence are irreversibly eroding the nation's natural capital. The restoration of degraded ecosystems, such as Lake Urmia or the Hamoun wetlands, would not only recover biodiversity but also restore livelihoods and cultural identity to local communities. In this perspective, interventions like Managed Aquifer Recharge (MAR), wetland restoration, and the protection of natural recharge areas are essential for rebuilding environmental resilience, despite being costly and slow to yield returns. International cooperation, particularly in the exchange of know-how and technology, could play a decisive role, provided the geopolitical context and sanctions regime allow for it.

5. Finally, the geopolitical dimension cannot be ignored. Iran shares strategic water basins with Afghanistan, Iraq, Turkey, and other neighboring countries. The absence of structured agreements for joint management risks turning scarcity into a source of conflict. Multilateral data-sharing platforms, joint management projects, and shared water infrastructure could, conversely, transform water from a potential trigger of instability into a powerful lever for regional resilience. In a Middle East marked by distrust and instability, "water diplomacy" could become not only a technical necessity but also a strategic opportunity to redefine regional relations.

Conclusion

Iran’s water crisis is far more than an environmental challenge; it directly threatens the foundations of food security, social stability, and national cohesion. While the crisis is rooted in the nation's harsh climatic conditions, its severity is the result of decades of economic and managerial decisions that have pushed natural resource use beyond sustainable limits.

Yet, water is not only a symbol of vulnerability but also a potential catalyst for renewal. A comprehensive rethinking of governance, agricultural practices, and infrastructure, paired with genuine regional cooperation, is not merely about ensuring the survival of water resources. It also offers Iran a critical opportunity to build a more resilient and equitable national model.

In this sense, the future of the Islamic Republic will depend on its capacity to transform the current crisis into an occasion for systemic change. This is a critical test that will demonstrate whether, even in a context of increasing scarcity, water can once again become a source of life and cohesion rather than a cause of conflict and division.

_____________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________

Bibliography

• Climate Diplomacy. Water stress and political tensions in Iran. https://climate-diplomacy.org/case-studies/water-stress-and-political-tensions-iran

• Collins, G. Iran’s Looming Water Bankruptcy. Center for Energy Studies, James A. Baker III Institute for Public Policy of Rice University, April 2017. https://www.bakerinstitute.org/sites/default/files/2017-04/import/CES-pub-IranWater-040317.pdf

• Haridy, S. Water Scarcity: A Catalyst for Iran's Mounting Domestic Challenges. Future for Advanced Research and Studies, September 2025. https://futureuae.com/en-US/Mainpage/Item/10416

• Hassaniyan, A. Iran’s water policy: Environmental injustice and peripheral marginalisation. Progress in Physical Geography: Earth and Environment, 2024, 48(3), 420–437. https://doi.org/10.1177/03091333241252523

• Hadei, M., & Hopke, K. P. Civilizational Drought: A Missing Category in the Understanding of Iran’s Water Crisis. Environmental Science & Technology, 2025, 59(27), 13529–13531. https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.est.5c07392

• Iran International. A Quarter of Iranian Farmers Unemployed in Last Seven Years. November 2022. https://www.iranintl.com/en/202211139676

• Lazard, O., & Adebahr, C. How the EU Can Help Iran Tackle Water Scarcity. Carnegie Europe, July 2022. https://carnegie-production-assets.s3.amazonaws.com/static/files/Lazard_Adebahr_-_Iran_Water.pdf

• Lotfollahi, M. Iran’s triple crisis is reshaping daily life. Al Jazeera, August 2025. https://www.aljazeera.com/news/2025/8/10/irans-triple-crisis-is-reshaping-daily-life

• Madani, K. Water management in Iran: what is causing the looming crisis? Journal of Environmental Studies and Sciences, 2014. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13412-014-0182-z

• Mojtahedi, N. Iran’s water crisis is real but man-made, climatologist argues. Iran International, August 2025. https://www.iranintl.com/en/202508019099

• Novak, P. Iran’s Agricultural Crisis: A Looming Threat to Food Security and Rural Livelihoods. Iran News Update, May 2025. https://irannewsupdate.com/news/economy/irans-agricultural-crisis-a-looming-threat-to-food-security-and-rural-livelihoods

• Paddison, L. This city could run dry ‘within weeks’ as it grapples with an acute water crisis. CNN, July 2025. https://edition.cnn.com/2025/07/31/climate/tehran-iran-water-crisis-day-zero

• Rahimi, M., Jalali, M., Zolghadr-Asli, B., AghaKouchak, A., & Mirchi, A. Water Governance and Policymaking in Iran Over the Last Half-Century: Inefficiencies and Shortcomings. EGU General Assembly 2025, EGU25-1308. https://doi.org/10.5194/egusphere-egu25-1308

• Reuters. Iranian president says country is on brink of dire water crisis. July 2025. https://www.reuters.com/sustainability/boards-policy-regulation/iranian-president-says-country-is-brink-dire-water-crisis-2025-07-31

• Sheikholeslami Kandelousi, N., & Syahkar, Z. Crisis Management of Water in Iran with a Futures Approach. SSRN, August 2024. https://ssrn.com/abstract=4929376

• Soltani, A., Pourshirazi, S., Torabi, B., Rahban, S., & Alimagham, S. Assessing climate change impacts on plant production and irrigation water demand at country level: analysis for Iran. Journal of Agriculture and Environment for International Development (JAEID), 2025, 119(1), 393–412. https://doi.org/10.36253/jaeid-16757

• Stimson Center. No Easy Solutions for Iran’s Water Shortages and Power Outages. March 2025. https://www.stimson.org/2025/no-easy-solutions-for-irans-water-shortages-and-power-outages

• Talebi, R. The Countdown to Iran’s Day Zero: A Crisis of Water, Not War. UnToldMag, April 2025. https://untoldmag.org/the-countdown-to-irans-day-zero-a-crisis-of-water-not-war

• Von Hein, S. Is Iran running out of water?. DW, June 2025. https://www.dw.com/en/is-iran-running-out-of-water/a-73548239

• Water Alternatives Films. Iran’s water crisis. 2016. https://www.water-alternatives.org/index.php/cwd/item/109-irancrisis

• Zargan, J., & Waez-Mousavi, S. M. The Effects of Water Crisis on Food Production in Iran. Ambient Science, 2016, 03(Sp2), 01–04. https://doi.org/10.21276/ambi.2016.03.sp2.ga01

Photo by AHMED JALIL

Abaqua

Via Cassia, 615

00189 Roma (RM)

© 2024. All rights reserved.

Codice Fiscale: 96584590580