Israeli Technological Innovation at the Service of Water Efficiency. An Example to Follow

Filippo Verre - February 15, 2023

* L’immagine di copertina di questo report è stata presa dal sito Israel Hayom, consultabile al seguente link: https://www.israelhayom.com/2019/07/21/un-showcases-israels-innovations-in-water-agriculture-technology/

In a largely desert territory like the Middle East, where water is considered a commodity more precious than gold, the management of water resources holds enormous strategic value. Israel, one of the most technologically advanced nations in the world, has for many years now entrusted the fate of its water supply to technology. The results are astonishing. Today, Tel Aviv not only no longer has water scarcity problems, but is also able to use the vast water resources at its disposal as a diplomatic tool to increase its influence in the region. This is not a given, since many other Middle Eastern nations are grappling with serious and persistent water crises. Jordan, Lebanon and Syria, for example, located at the same latitudes as Israel, are very far from obtaining the same levels of water security achieved by the Jewish state. Damascus, in particular, suffers cyclically from water stress at various levels. According to some studies, this characteristic was at the root of the disorders that led to the civil war that broke out in 2011[1], which is still not entirely resolved, especially in the northern reaches of the Arab nation.

A careful and profitable management of water has mainly social implications, not only economic and productive ones. Being the primary good par excellence, indispensable for any form of life, water represents the cornerstone for any community. Nations poor in water resources, in addition to having less than excellent economic performances, are subject to recurrent social disorders[2], often exacerbated by environmental crises caused by the lack of water. Conversely, countries that can boast an efficient water distribution and supply system – such as Israel – usually have high rates of internal stability and notable development economies. This is because, among other things, water enters practically every production process, from the industrial sector to the catering sector, up to key sectors of a nation such as, for example, healthcare or energy production.

This report will highlight Israel’s water strategies with a particular focus on the role technology plays in ensuring Tel Aviv has one of the most efficient systems not only in the Middle East but also on the global stage. It will also highlight some hi-tech companies specialized in various fields, from desalination to drip irrigation, from wastewater treatment to dew collection for irrigation purposes. The example set by Israel, which over time has, in effect, created a “garden from the desert,” can and should be followed by other nations that find themselves dealing with dangerous cases of water stress.

Israel and the Water Supply Dilemma (WSD)

The issue of Israel’s water supply has been a dilemma that was not easily resolved even before the Jewish state came into being. As early as 1902, the writer Theodor Herzl theorized in his historic work Altneuland (The New Land) the creation of a bold plan for the transport of large quantities of water in the desert of what was then Palestine, at that time the Ottoman Vilayet[3]. Herzl proposed, essentially, to take water from the Jordan River for irrigation and supply purposes. The limited technological capabilities of that time prevented this plan from being realized. However, the need to increase water resources in that territory found more and more supporters. Thirty-five years later, in 1937 – therefore, on the eve of the Second World War and over a decade before the foundation of the State of Israel – a company specialized in the water sector was created: Mekorot. The latter is currently Israel's national water company and the country's main agency for water management. Mekorot supplies 90% of Tel Aviv's drinking water and operates a water supply network throughout the territory through the so-called National Water Carrier (NWC). In addition, it should be noted that Mekorot has a recognized international profile, as its subsidiaries have cooperated with numerous countries around the world in sectors such as desalination, water purification and water supply systems[4].

Fig. 1: Logo di Mekorot, la compagnia idrica nazionale di Israele

https://www.mekorot-int.com/

The great attention paid to the so-called Water Supply Dilemma (WSD) – as mentioned, even before Israel was born as a nation – testifies to a far-sighted strategic vision by the leaders of the future Jewish state. In fact, the desert characteristics of the territory were compounded by the growing number of people of Jewish origin who, starting from the last two decades of the nineteenth century, began to flock to Palestine. This was the phenomenon called Aliyah, or Jewish immigration to the land of Israel, caused by the increase in pogroms and the growth of anti-Semitic nationalism in various parts of Europe. In the space of a few years, hundreds of thousands of people settled in that area, inevitably causing logistical problems. A greater number of people automatically favored water stress in a region that already endemically suffered from crises related to the water supply.

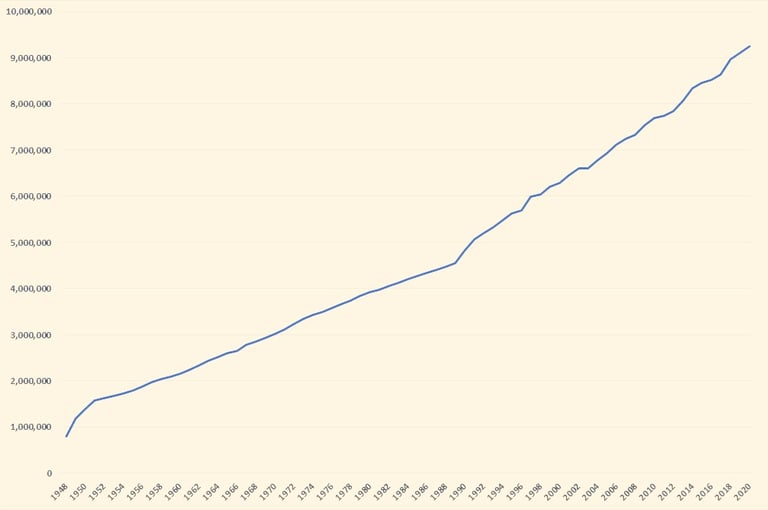

So, from a water perspective, the demographic issue has been a central aspect for the authorities since the dawn of the modern Jewish state, who have had to deal with increasing rates of population settled on a mostly arid territory. Even today, Israeli demography – dynamic and rapidly growing – forces Tel Aviv to increase the availability of water for its residents year after year. In this regard, consider some data. With a growth of 2% per year, the Israeli population is experiencing the strongest demographic increase in the so-called "developed world". If the birth rate remains constant, the Israeli Central Bureau of Statistics estimates that within thirty years it could reach 17.6 million inhabitants, almost double the current 9 million[5]. In essence, by 2050, Israel could become a more polluted, densely populated country with far fewer open spaces. According to a study prepared by Tzafuf [6], the National Population Forum, the number of Israeli families will double and continue to grow over the next 45 years[7].

Fig. 2: Crescita demografica israeliana dal 1948 al 2020

https://www.jewishvirtuallibrary.org/graph-of-israeli-population-growth

If the current demographic trend continues, the hydro-logistical challenges that Tel Aviv authorities would have to face would be daunting to say the least. The pace of housing construction in 2040-2050 is set to increase exponentially, as Israel will have to build twice as many apartments in that decade as it did in 2010-2020. Furthermore, at the current birth rate, the Central Bureau of Statistics predicts that about 10% of open space will be lost by mid-century, as land will be needed for housing, infrastructure, and large-scale solar power plants.

To cope with the skyrocketing population, Israel will have to increase electricity production, build more roads, schools, hospitals, and so on. Likewise, water needs are expected to grow just as dramatically. According to the forecasts of Calcalist, an Israeli economic newspaper, water consumption will increase from the current 2,200 million m³ per year to over 3,500 million m³ if fertility is drastically reduced, to 4,000 million m³ in the case of a slight contraction and 4,500 if no changes occur[8]. In any case, therefore, national water consumption will most likely increase sharply in the near future. At the same time, moreover, the availability of water in nature is expected to decrease somewhat due to climate change[9]. In this regard, while the rest of the world is trying to avoid a temperature increase of 1.5 degrees centigrade, it is expected that the Middle East will see an increase of as much as 4 degrees. Much of this region will become essentially almost unlivable during the long and torrid summer period. In this perspective, some studies presented by the University of Tel Aviv indicate that in the Middle East, by the end of this century, the summer months will increase by 50%, with rainfall forecasts decreasing by up to 40%.

Therefore, in light of growing demographic phenomena and increasingly persistent environmental criticalities, water supply takes on an absolute strategic centrality in planning the management not only of the economy but also of the Israeli society of the future.

Israel and water stress: a battle won

Currently, Israel produces 20% more water than it needs. This is a truly impressive result, achieved after decades of research, planning and investments. It is even more so if we consider that, even today, approximately four billion people experience cases of serious water scarcity every day due to various factors, including the climate crisis, the associated rise in temperatures and water pollution[10].

From the earliest years of its existence, the Jewish state was able to count on a robust company specializing in the construction of water networks. In fact, the aforementioned Mekorot, starting in early 1948, began to irrigate the four corners of the small Middle Eastern nation with the precious “blue gold” through the aforementioned National Water Carrier, completed in 1964, shortly after the founding of Israel. This water transport network was designed to pump water from Lake Kinneret (Lake Tiberias) and transfer it with the help of regional water infrastructures to the central and southern territories, as can be seen in Fig. 3. However, the population of the young state continued to increase, driven both by the high fertility rates of Israeli women and by the constant migration that continued to regularly bring in new residents from various parts of the world. In addition, consider that approximately 80% of the water transported by the NWC was destined for agriculture, an activity that still represents the preferred destination for water resources throughout the world. According to various studies, in fact, the agricultural sector is the recipient of over 70% of the fresh water that humans use.

The National Water Carrier, in essence, alone was not able to satisfy Israel's water needs. The solution was found thanks to the intuition of Simcha and Yeshayahu Blass who, starting in 1959, began to develop an irrigation technique that would revolutionize the use of water in the agricultural sector: the so-called drip irrigation, or drip irrigation[11]. Therefore, five years before the completion of the NWC, the Blasses identified a method to drastically reduce the use of water intended for irrigation purposes and, therefore, allocate increasing quantities of water to civil supply, one of Israel's main objectives in those years.

Fig. 3: Il National Water Carrier di Israele

https://embassies.gov.il/MFA/AboutIsrael/Maps/Pages/Israel-Water-Resources.aspx

In 1965, the two decided to export their idea on a national scale by founding Netafim, a company that would become a top global player in the production and marketing of irrigation technologies. Today, drip irrigation accounts for about 75% of Israeli farmland, compared to a meager 5% worldwide.

Drip irrigation was not the only technique used to alleviate Israel’s water stress. In fact, several ideas came to light to more effectively use the modest reserves of fresh water that Tel Aviv had available. Very cleverly, starting in the 1980s, some engineers began working on how to exploit water sources previously considered unusable, such as wastewater. In this regard, in 1985 Israel began sending wastewater, which was treated and made reusable, through its National Water Carrier (NWC) to farms, significantly reducing the gap between agricultural consumer demand and available water. The aim of this approach was to use recycling as a tool to increase the resource for agriculture without affecting the reserves for civil supply. This has been a very successful approach, since Israel currently uses almost 90% of recycled water for agricultural purposes[12] and has the objective of reaching 95% by 2025. For comparison, the country that comes closest to these data, so to speak, is Spain with 17% of recycled water destined for irrigation.

With a daily inflow of approximately 470,000 m³ of raw wastewater, the Shafdan plant is the largest wastewater treatment plant in Israel; it supplies approximately 140 million m³ of clean, reclaimed water to farms in the Negev Desert for irrigation each year. In fact, more than 60% of agriculture in the Negev is supplied by the Shafdan plant alone. In addition, the Israel Green Development Organization (KKL-JNF) has built 230 reservoirs that store treated wastewater for agricultural use. Each year, these reservoirs add up to 260 million m³ of water to Israel’s water supplies. KKL-JNF has also established several phytoremediation and biofilter projects, where plants remove nearly 100% of pollutants from urban stormwater runoff to provide an additional source of non-potable but usable water for agricultural irrigation.

Fig. 4: Impianto di trattamento delle acque reflue di Shafdan

https://www.mekorot-int.com/blog/project/shepdan/

If drip irrigation has revolutionized irrigation techniques by allowing for substantial savings in resources and if the recycling of treated water has increased Israel's water availability, desalination has allowed the small Middle Eastern nation to completely free itself from the phenomenon of water scarcity that had gripped Israel for years. Currently, desalinated water plays a fundamental role in supplying Tel Aviv's water basket with precious resources. The construction of the plants began at the end of the old millennium, when, precisely in 1999, the Israeli government launched a desalination program centered on the reverse osmosis of sea water. Israel believed in this project from the very beginning, so much so that it quickly began the construction of five large-scale desalination plants that became operational in a short time: the Ashkelon plant (2005) capable of producing 118-120 million m³ of drinking water per year; Palmachim (2007), which today produces 90-100 million m³ of water annually; Hadera (2009) capable of producing 127 million m³, Sorek (2013) which produces 150 million m³ of water per year and Ashdod (2015), which produces 100 million m³ of desalinated water every twelve months.

In addition to these five infrastructures, Israel has recently begun construction of two more desalination plants, one of which should be operational by 2023. According to some studies, these new arrows in the Israeli water quiver will have a combined capacity of 300 million m³ per year. Upon completion of the seventh plant, desalinated water will cover up to 90% of the annual consumption of municipal and industrial water in the Jewish state. The authorities aim to produce approximately 1.1 billion m³ of desalinated water per year. This is a truly impressive result, achieved after years of great sacrifice, work and planning. Let us not forget, in fact, that only 15 years ago, despite the far-sighted vision of its leaders and the constant attention paid to water supplies, Israel was struggling with a very serious drought[13]. Lasting almost a decade, the latter “burned” the entire Middle East, to the point of touching the western edges of the Fertile Crescent. Between 2010 and 2015, Israel's largest source of fresh water, Lake Tiberias, fell almost to the edge of the so-called “black line”, where an infiltration of salt would have flooded the lake, damaging it almost irreparably.

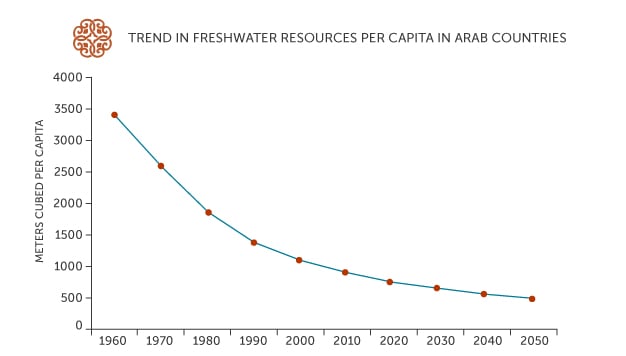

Similarly, in other areas of the Middle East, the severe drought of 2008 caused enormous inconvenience. For example, when the situation worsened, causing the water table to essentially sink, Syria’s farmers chased it, drilling wells 100, 200, then 500 meters deep in a literal hunt for groundwater. Eventually, the wells ran dry, and Syria’s agricultural production collapsed in an epic sandstorm. More than 1 million farmers crowded into shantytowns on the outskirts of Aleppo, Homs, Damascus, and other cities in a futile attempt to find work. Similar stories played out across the Middle East, where drought and agricultural collapse have produced a “lost generation,” with no prospects and a lot of resentment. Iran, Iraq, and Jordan, in particular, have faced similar water catastrophes, with water shortages sending the entire region into a spiral of severe hardship.

Fig. 5: Assottigliamento delle risorse idriche pro capite nel corso degli anni nei Paesi arabi

https://www.mei.edu/publications/climate-change-middle-east-faces-water-crisis

Today, at least as far as Israel is concerned, the situation has completely reversed. As mentioned, in fact, thanks to a diversified water supply strategy, Tel Aviv is able to produce more water than it needs. Lake Tiberias, the country's main fresh water reserve, is the emblem of this new era of water abundance that characterizes the Jewish state. In 2018, the last year of the ten-year drought, the lake on whose waters (according to the account of some Gospels) Jesus walked[14], was literally drying up. Its tributaries, including the Jordan River, brought less and less water and what did flow contained more and more saline molecules, dangerous for the biological health of the lake. With a surface area of 166 km², the Kinneret – according to the Hebrew name – has the particularity of being over 200 meters below sea level. This makes the entire lake basin extremely humid, a condition that facilitates the phenomenon of water evaporation. Thus, the combined effect of drought, lowering of the water level, increase of the saline component and evaporation was rapidly putting at risk the hydro-environmental stability of the Sea of Galilee[15].

To solve this thorny problem, a few years ago the government of Tel Aviv developed a revolutionary strategy, based on pumping desalinated water directly into the lake through an artificial canal. This project, costing 900 million shekels (240 million euros), has the objective of maintaining the water level of the lake constant especially during periods of drought. Mekorot has supervised the construction of a 13 km underground pipeline that connects the lake to the infrastructure which in turn is connected to the other five desalination plants located on the Mediterranean coast. The desalinated water is then channeled into the Tzalmon River, which flows directly into Lake Tiberias, near Kibbutz Ginosar on the northwestern shore, ensuring a constant source of supply to the lake basin.

Strategic implications of Israeli technology serving the water sector

Without a doubt, high technology is the main reason behind Israel’s success in the water sector. This has important strategic implications that are worth highlighting. First of all, the availability of a certain stock of water resources, regardless of the increasingly unstable climate conditions in the Middle East region, allows Tel Aviv to implement an industrial policy protected from cases of water scarcity. This generates positive effects both at an economic level and in the planning phase. Once the supply has been secured and therefore, no longer having to use an emergency approach to the “water” issue, Tel Aviv has laid the foundations to technologically expand its water know-how even further. In this regard, there are many Israeli companies that have devised daring techniques to find, preserve and use the precious “blue gold” in its various forms. Here, the focus will be on Asterra and Tal – Ya, two highly successful entrepreneurial realities capable of imagining new ways to optimize the use of water.

Fig. 6: Logo di Asterra

https://asterra.io/

Fig. 7: Logo di Tal – Ya

http://www.tal-ya.com/

Asterra, originally founded under the name Utilis, is responsible for carrying out satellite surveys aimed at discovering underground water reservoirs. Created in 2013 by Lauren Guy, a young entrepreneur with a background in geophysics, this company initially specialized in studying the Martian surface in search of ice deposits in the Red Planet's subsoil. After having achieved some success, Guy decided to partially, but not teleologically, convert the company's business model and dedicate itself to the search for water on Earth, which is much closer and equally in need of water resources. The technology it had developed to operate on Mars, located several million km from our planet, could easily be used for the exact same purposes on the Earth's surface. A system focused on the use of artificial intelligence applied to an ad hoc algorithm allows the presence of the precious liquid to be revealed without drilling in search of water tables or artesian wells. Clearly, the strategic implications that this company can offer to countries struggling with water crises are many. They range from high success rates in the search for underground water, to the containment of costs for carrying out physical surveys – which can be profitable if aquifers are found, but also fruitless – up to respecting the environment, subjected to minimal inconvenience given the high technology that Asterra makes available.

In 2016, the company added another important business activity: the detection of leaks in underground water systems, which has then progressively become the primary application used commercially by Asterra. From an orbiting satellite, a band of the radio spectrum “penetrates” the Earth’s surface and, through an algorithm developed to detect underground water, is able to detect underground leaks of up to 0.5 liters per minute. Underground pipe leaks, in addition to being a serious damage to aqueducts, take an average of 18 months to surface and, when they do, significant volumes of water are irreparably lost. Asterra estimates that nearly 64 billion liters of water worldwide are wasted every day due to leaks. The company founded by Guy uses a series of artificial intelligence technologies to analyze obsolete piping systems and provide monitoring data to water managers to address maintenance problems. This is truly cutting-edge technology that is the result of top-level aerospace techniques. In this regard, a couple of years ago in 2021, Utilis decided to change its commercial name to “Asterra”, from Astra, the Latin name for “stars”, Asterion, the Greek river deity, and Terra, our planet[16].

The other reality that is interesting to focus on is Tal – Ya, an Israeli company that has created an irrigation system that works with dew. Not too dissimilar from the idea that led to the creation of drop irrigation, Tal – Ya Water Technologies has conceived a new product that allows dew to be compressed from the air, allowing crops to be watered while saving precious quantities of water. From a technical point of view, the procedure is as follows: a square serrated tray made of a special type of plastic is placed on the ground. The tray (which is not disposable) has a central hole to allow the plant to develop. The characteristic of reuse is given by the fact that they are built with recycled and recyclable non-PET plastic with UV filters added with limestone; this prevents the device from degrading in the sun or after the application of pesticides or fertilizers. An aluminum support helps the trays to adapt to possible temperature variations between night and day.

This ingenious technique actually dates back several centuries. The ancient Israelites used special limestone stones to try to collect dew from the air, with interesting but modest results. In fact, these stones were rarely able to collect large quantities of the resource. At most, enough water could be obtained to quench the thirst of a handful of individuals. Currently, with Tal – Ya's intuitions and existing modern technologies, much more resource can be collected to be used for irrigation purposes. Even in this case, therefore, the environmental and economic benefits are notable for the end users of this technique, both from the point of view of moderate ecological impacts and in terms of cost containment.

In addition to the advantages for the private sector, the precious technological know-how that Israel has been able to build up over these decades has strategic implications on the national level and in terms of so-called hydro-diplomacy. The high production of water through the aforementioned desalination plants allows Tel Aviv to manage a water surplus that can be used in negotiations with other Middle Eastern nations, often struggling with water crises. In this perspective, it is interesting to study the hydro-diplomatic relations between Jordan and Israel. These two countries, respectively in need of water and energy, have recently reached an agreement – called the Israel / Jordan Peace Treaty – on the mutual supply of resources considered indispensable for the economic growth and social stability of both. Essentially, according to the treaty, Tel Aviv will sell water in exchange for solar energy, abundant in Jordan given its large desert surface. Once fully in force, the agreement between the two Middle Eastern nations could become a real turning point for the entire region. Israel would obtain a lot of renewable energy at a lower cost, resulting in strengthened regional cooperation. Jordan, for its part, would achieve water security through the purchase of Israeli desalinated water and would become a major exporter of green energy. The United Arab Emirates are also involved in this project, which would finance the construction of solar power plants in Jordan in order to obtain energy to be transferred to Israel[17].

The economic implications for all parties involved would be very significant. According to the EcoPeace study center, by 2050 Jordan, by providing about 20% of Israel's energy needs, would increase its GDP by 3-4% on an annual basis, in addition to purchasing desalinated water from the Mediterranean in quantity. As for Israel, the economic and energy benefits would be equally positive. Amman today produces electricity through the exploitation of the sun at less than 3 cents per kilowatt hour, while throughout the Jewish state electricity is sold at 10 cents per kilowatt hour or more. In fact, therefore, Jordanian solar energy is not only more sustainable, but also much cheaper. Moreover, Jordan, not having easy access to sea water for desalination – with its only sea point located far from its capital and major population centers – spends three to four times more to bring desalinated water from the Red Sea than Israel incurs to pump desalinated water from the Mediterranean coast[18]. In essence, therefore, this hydro-diplomatic agreement is a classic win-win situation that fully satisfies all parties involved.

Conclusion

In light of what has been analyzed in this report, Israel today can easily be considered a true water power. The efficiency of its technological sector, cutting edge in many respects, guarantees Tel Aviv not only water security but also a notable surplus of resources that, as we have seen, are effectively used in some foreign policy strategies of the Jewish state. In this regard, it is interesting to note the integrated regional development approach that Israel has been proposing for years now. On the model represented by the European Union - first established as an economic community focused on the common management of coal and steel (April 1951) and then gradually becoming a federation of states linked by very close institutional relations - Tel Aviv believes that the increase in economic exchanges between Middle Eastern nations can promote peace and stability in the region. In this regard, water plays a decisive role given its high demand in many regions of the Middle East. Being able to count on a lot of resources, Tel Aviv is able to propose exchanges that favor an increasingly strong integration between the countries with which it borders. Instead of coal and steel, the economic community that the Israelis are aiming for would be based on the exchange of water and energy.

Despite the high benefits that technology has brought to Israel's water sector, one cannot help but highlight some critical issues. For example, regarding the high production of desalinated water, the spearhead of the Israeli water sector, there has been no shortage of criticism over time from the most skeptical. For example, the high consumption of fossil fuels necessary to produce so much desalinated water has not been viewed favorably. Furthermore, the project to have desalinated water flow into Lake Tiberias in order to prevent the progressive erosion of its waters has been criticized. In support of this thesis, some experts have argued that, even if free of its saline component, the water released into the lake would cause serious biological damage to the lake ecosystem.

Both criticisms have been rejected. Fossil fuels, used in quantity during the first years of operation of the plants, are today less and less necessary thanks to the production of solar energy that also powers the desalination plants. In this regard, one of the reasons that pushed Tel Aviv to stipulate the hydro-energy agreement with Jordan concerns precisely the introduction of clean energy into the Israeli basket to continue producing desalinated water with sustainable environmental impacts. Furthermore, regarding the criticism regarding the water released into Lake Tiberias, other experts have reiterated that the biological difference between the two waters exists but is minimal. And, furthermore, the ecological survival of the lake has priority over modest biological changes. This water basin, in fact, is not only very important for Israel, but represents an important source of supply for Syria and Lebanon[19].

Israel has solved one of its main dilemmas, namely the fight against water insecurity, for many years now. Certainly, there are many tests that the leaders of the Jewish state still have to face and try to resolve, especially with regard to the constant tension that hovers not only within its own borders but, above all, in the Middle Eastern regional context. However, the abundance of water, obtained after many decades of sacrifice and innovation, that Tel Aviv has today can be considered a real strategic advantage. The great availability of water resources ensures Israel, at least from a theoretical point of view, a future of development and social and economic growth not found in the entire Middle East.

Bibliografia:

Articoli accademici

Maurus Reinkowski, Late Ottoman Rule over Palestine: Its Evaluation in Arab, Turkish and Israeli Histories, 1970-90, in “Middle Eastern Studies”, Vol. 35, No. 1, 1999, pp. 66-97.

Mesfin Mekonnen & Arjen Y. Hoekstra, Four billion people facing severe water scarcity, in “Sciences Advances”, Vol. 2 Issue 2, 2016, pp. 1-7.

Peter H. Gleick, Water, Drought, Climate Change, and Conflict in Syria, in “Weather, Climate, and Society”, Vol. 6, No. 3, 2014, pp. 331-340.

Pola Lem, Could a Lack of Water Cause Wars? Water scarcity poses a greater risk of turmoil under global warming, in “Scientific American”, 2016.

Shahzaib Ahmad et. al., Impact of water insecurity amidst endemic and pandemic in Pakistan: Two tales unsolved, in “Annals of Medicine and Surgery”, Vol. 81, 2022.

David Katz and Arkady Shafran, Water-Energy Nexus: A Pre- Feasibility Study for Mid-East Water-Renewable Energy Exchanges, in “EcoPeace” – Middle East and Konrad Adenauer Stiftung, novembre 2017.

Periodici e quotidiani

Abigail Klein Leichman, Turn the Flood inot a Drip. Urges Netafim CEO, in “Israel21c”, 13 aprile 2022.

Cristina Bufi Poecksteiner, Israele, una delle nazioni più aride del mondo, adesso sta traboccando d’acqua, in “Global Voices”, 11 gennaio 2019.

Christophe Lafontaine, Demografia, in trent’anni Israele raddoppia, in “TerraSanta.net”, 29 giugno 2021.

Lior Novik, Israel has built an exceptional, resilient water economy, in “The Jerusalem Post”, 12 agosto 2022.

Max Kaplan-Zantopp, How Israel used innovation to beat its water crisis, in “Israel21c”, 28 aprile 2022.

Max Kaplan-Zantopp, The Steps Israel must Take to Avoid a Future Water Crisis, in “Israel21c”, 12 maggio 2022.

Melanie Lidman, Plan to pump desalinated water to Sea of Galilee may open diplomatic floodgates, in “The Times of Israel”, 27 giugno 2019

Paolo Castellano, Cresce la popolazione di Israele. Oltre i 9 milioni alla vigilia di Yom HaAtzmaut, in “BET. Magazine Mosaico – Sito Ufficiale della Comunità Ebraica di Milano”, 14 aprile 2021.

Rena Lenchitz, Israel Leads World In Wastewater Reclamation, But Solution Is Not Perfect, in “No Camels”, 30 agosto 2021.

Thomas Coex, Si sta seccando il lago più famoso dei Vangeli, in “Il Post”, 1 dicembre 2018.

Yuval Azulai, The climate crisis will cause a surge of migration. You can’t stop hungry people, in “Calcalist”, 29 agosto 2022.

_______________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________

[1] Qualche anno prima della crisi scoppiata nel 2011, nel 2006 una grave siccità spinse migliaia di agricoltori siriani a migrare verso i centri urbani, ponendo le basi per le massicce rivolte che si sarebbero verificate poco tempo dopo, dando l’inizio ad una sanguinosa e logorante guerra civile. Per maggiori dettagli si rimanda a Peter H. Gleick, Water, Drought, Climate Change, and Conflict in Syria, in “Weather, Climate, and Society”, Vol. 6, No. 3, 2014, pp. 331-340.

[2] Cfr. Pola Lem, Could a Lack of Water Cause Wars? Water scarcity poses a greater risk of turmoil under global warming, in “Scientific American”, 2016 e Shahzaib Ahmad et. al., Impact of water insecurity amidst endemic and pandemic in Pakistan: Two tales unsolved, in “Annals of Medicine and Surgery”, Vol. 81, 2022.

[3] Cfr. Maurus Reinkowski, Late Ottoman Rule over Palestine: Its Evaluation in Arab, Turkish and Israeli Histories, 1970-90, in “Middle Eastern Studies”, Vol. 35, No. 1, 1999, pp. 66-97.

[4] Per maggiori dettagli si rimanda a Lior Novik, Israel has built an exceptional, resilient water economy, in “The Jerusalem Post”, 12 agosto 2022.

[5] Christophe Lafontaine, Demografia, in trent’anni Israele raddoppia, in “TerraSanta.net”, 29 giugno 2021.

[6] Tzafuf significa «sovraffollato» in ebraico; si tratta di una ONG fondata da un gruppo di ricercatori, accademici e di ambientalisti.

[7] Paolo Castellano, Cresce la popolazione di Israele. Oltre i 9 milioni alla vigilia di Yom HaAtzmaut, in “BET. Magazine Mosaico – Sito Ufficiale della Comunità Ebraica di Milano”, 14 aprile 2021.

[8] Christophe Lafontaine, Demografia, in trent’anni Israele raddoppia, in “TerraSanta.net”, 29 giugno 2021.

[9] Yuval Azulai, The climate crisis will cause a surge of migration. You can’t stop hungry people, in “Calcalist”, 29 agosto 2022.

[10] Mesfin Mekonnen & Arjen Y. Hoekstra, Four billion people facing severe water scarcity, in “Sciences Advances”, Vol. 2 Issue 2, 2016, pp. 1-7.

[11] Max Kaplan-Zantopp, How Israel used innovation to beat its water crisis, in “Israel21c”, 28 aprile 2022.

[12] Questo dato risulta, tra l’altro, in crescita, visto che pochi anni fa (2015) Tel Aviv utilizzava “solo” l’86% dell’acqua riciclata per scopi agricoli. Per ulteriori dettagli su questo aspetto si rimanda a Rena Lenchitz, Israel Leads World In Wastewater Reclamation, But Solution Is Not Perfect, in “No Camels”, 30 agosto 2021.

[13] Cristina Bufi Poecksteiner, Israele, una delle nazioni più aride del mondo, adesso sta traboccando d’acqua, in “Global Voices”, 11 gennaio 2019.

[14] Secondo i Vangeli, proprio sulle sponde del Lago di Tiberiade Gesù scelse alcuni dei suoi apostoli e realizzò uno dei suoi miracoli più famosi, ovvero la moltiplicazione dei pani e dei pesci.

[15] Thomas Coex, Si sta seccando il lago più famoso dei Vangeli, in “Il Post”, 1 dicembre 2018.

[16] Max Kaplan-Zantopp, The Steps Israel must Take to Avoid a Future Water Crisis, in “Israel21c”, 12 maggio 2022.

[17] David Katz and Arkady Shafran, Water-Energy Nexus: A Pre- Feasibility Study for Mid-East Water-Renewable Energy Exchanges, in “EcoPeace” – Middle East and Konrad Adenauer Stiftung, novembre 2017.

[18] Melanie Lidman, Plan to pump desalinated water to Sea of Galilee may open diplomatic floodgates, in “The Times of Israel”, 27 giugno 2019.

[19] Abigail Klein Leichman, Turn the Flood into a Drip. Urges Netafim CEO, in “Israel21c”, 13 aprile 2022.

Abaqua

Via Cassia, 615

00189 Roma (RM)

© 2024. All rights reserved.

Codice Fiscale: 96584590580