EU's Strategy for Water Resilience

Pietro Secchi - December 2, 2025

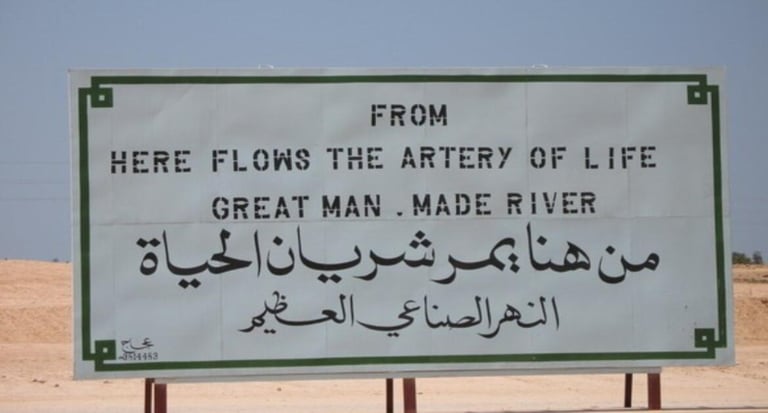

* L’immagine di copertina di questo paper è stata presa dal seguente link: The eighth wonder of the world?

Genesis of an Idea

Libya is predominantly an immense desert, ranking as the sixth driest country in the world, with annual rainfall below 100 mm, high evaporation rates, and an almost total absence of permanent watercourses. In such a harsh environment, human settlements and economic activity have historically been concentrated along the narrow Mediterranean coastal strip, where rainfall is relatively higher and maritime routes ensure vital connections to the outside world.

Until the 1960s, the country’s water supply relied mainly on coastal springs, traditional wells with irregular yield, and temporary aquifers, while major cities - Tripoli, Benghazi, and Misurata - depended on diminishing reservoirs and costly, unreliable desalination plants, placing Libya on the brink of structural water scarcity.

In this context of extreme vulnerability, the discovery of vast underground reservoirs in the desert took on an almost epochal significance, radically redefining the relationship between the territory and the country’s water resources.

In the 1930s, American geologists searching for water in Saudi Arabia instead discovered oil. In Libya, early exploration campaigns in the 1950s revealed a dual wealth: alongside petroleum deposits emerged immense reserves of fossil freshwater, trapped for tens of millennia in the Saharan sandstone. These studies led to the identification of the Nubian Sandstone Aquifer System (NAS) and other connected basins, extending beneath much of North Africa. The waters, of extremely ancient pluvial origin, are no longer replenished by the current hydrological cycle; their “non-renewable” nature grants them extraordinary strategic and scientific value, transforming them into a continental resource of exceptional importance. Estimates suggest roughly 150,000 km³ of water spread over more than two million km², with aquifers reaching depths of up to four kilometers - a silent ocean hidden at the heart of the desert.

Between the 1960s and 1970s, Libya rapidly transitioned from a rudimentary extractive economy to a state fueled by oil revenues. Yet accelerated modernization did not solve the water crisis: coastal settlements continued to rely on local resources and inefficient desalination plants.

Following the 1969 coup, Muʿammar Gaddafi elevated national self-sufficiency to a strategic principle. Major infrastructure projects became tools of political legitimation and symbols of revolutionary power: the “blue gold” hidden beneath the Sahara assumed, in the vision of the new Libyan leadership, a central role in a project of material independence and ideological pride.

Feasibility studies demonstrated that extracting and transporting fossil water was more cost-effective than desalination, even considering energy costs. The external technological dependence implied by desalination also conflicted with the Jamahiriya’s principles of autarky. The Great Man-Made River (GMR) project was therefore conceived with a dual purpose: to ensure water security for the population and to serve as a symbol of emancipation from the West.

Initially, the goal was not merely to supply water to coastal cities but to support a broader strategy of internal colonization and desert development. According to the original plans, the southern Fezzan regions - Murzuq, Sarir, and Kufra - were to become agricultural and residential hubs, balancing population distribution and strengthening food self-sufficiency. However, pilot projects in the 1970s faced logistical, climatic, and social obstacles.

The strategy thus evolved from the paradigm of “bringing people to water” to “bringing water to the people,” focusing on the modernization of water and urban infrastructure along the coast. The GMR eventually consolidated into a national water-transfer network, becoming an instrument of territorial unification and state-building through the management of water.

The Desert Construction Site (1983–2010)

In 1983, the Libyan government established the Great Man-Made River Authority (GMRA), the agency tasked with designing, constructing, and managing an unprecedented project: a national water system capable of transporting fossil water from the heart of the Sahara to the Mediterranean coastal cities.

The following year, Muʿammar Gaddafi symbolically laid the first stone in Sarir, officially inaugurating a project that would become the largest hydraulic undertaking ever attempted in Africa and one of the most ambitious civil engineering endeavors of the 20th century.

Under the direct control of the General People’s Committee, the GMRA operated as a quasi-independent ministry, endowed with extraordinary powers in planning, expropriation, and contracting with foreign companies. Its hybrid structure - hierarchical yet technically advanced - enabled the coordination of construction sites and logistics across a vast territory, largely lacking preexisting infrastructure.

The Great Man-Made River project developed - and continues to develop - in multiple construction phases, conceived as successive stages of a unified yet progressive design: gradually transporting water from the southern aquifers toward Tripolitania and Cyrenaica, creating a system of interconnected parallel pipelines.

Phase I (1984-1991): Establishing the Infrastructure. The first phase, officially inaugurated in 1984, focused on the development of the Sarir and Tazerbo well fields in the eastern Sahara, where hundreds of wells were drilled up to 500 meters deep. Water was conveyed through over 1,600 kilometers of pipelines, with a daily capacity exceeding 2 million cubic meters. The main route ran toward the eastern coast, passing through Ajdabiya and reaching Sirte and Benghazi. Along this axis, new industrial hubs emerged - most notably the Brega pipe factory, entirely designed to produce the massive reinforced concrete segments on-site - and a logistical network of roads, reservoirs, and pumping stations was established.

Phase II (1989-1999): Expansion toward the Capital. The success of Phase I cemented the project as a cornerstone of national development policy. Phase II, launched in 1989 and partly overlapping with the first phase, aimed to extend the network westward to supply Tripoli and Misurata, the country’s largest urban centers. A new pipeline backbone of over 2,000 kilometers was built, connecting the Sarir, Tazerbo, Kufra, and Murzuq basins to the Jabal al-Hasawna well field, located in one of the most remote areas of the desert. Here emerged the beating heart of the system: 484 wells spread across 19,000 km², capable of delivering several million cubic meters of water per day.

Phase III (2000–2009): Consolidation and Balancing. Phase III focused primarily on strengthening and harmonizing the infrastructure to ensure a more balanced distribution of water resources between the east and west of the country. Significant interventions included the expansion of Phase I with approximately 700 kilometers of new pipelines and the installation of additional pumping stations, increasing the system’s total capacity to 3.68 million cubic meters per day. A northern branch toward Tobruk, approximately 500 kilometers long and supplied by wells in the Jaghbub oasis, was also constructed to enhance water security in eastern Cyrenaica and maintain supply continuity for local communities and infrastructure. This phase not only consolidated the existing network but also represented a strategic step toward balancing national water flows, reducing the risk of regional disparities, and strengthening the system’s resilience amid growing urban and industrial demand.

Phases IV and V (2010–2011): Completion Interrupted. Phases IV and V, planned between 2010 and the immediately following period, were intended to complete the national network, extending connections toward Ghadames, Zuwara, and western Tripolitania. However, the 2011 revolution and subsequent conflicts halted their implementation. The unfinished final sections were meant to close the infrastructure loop, transforming the Sahara into a permanent reservoir of life. Instead, the interruption of work marked the end of the era of engineering optimism and the beginning of a prolonged period of uncertainty.

The Post-Gaddafi Period

The Great Man-Made River (GMR) continues to be Libya’s primary source of water supply, still providing over 90% of the country’s freshwater, with an average daily transfer of approximately 6.5 million cubic meters from the desert’s fossil aquifers to the main coastal cities. The water network, comprising over 4,000 kilometers of main pipelines, around 1,300 wells, numerous pumping stations, and storage reservoirs, remains the backbone of the national water system.

However, with the fall of Muʿammar Gaddafi’s regime in 2011, the GMR lost the political direction and centralized management that had ensured its development and operation for nearly thirty years. Initially conceived as a symbol of national sovereignty and water self-sufficiency, the infrastructure gradually ceased to serve as a pillar of development, becoming vulnerable strategic assets within a context of fragmented governance and widespread conflict. The civil war and the collapse of state institutions further exacerbated the system’s fragility.

From an infrastructural perspective, roughly one-third of the project remains incomplete, with crucial branches to the south and west never brought into operation. Maintenance of the facilities has become extremely precarious, and the Sarir, Tazerbo, and Jabal al-Hasawna well fields - vital nodes of the network - have frequently been targeted by sabotage, theft, and deliberate attacks. Similarly, the Brega pipe factory suffered significant damage following a NATO airstrike in May 2011.

Operationally, the centralized network has gradually fragmented into segments controlled by local militias, municipalities, or informal consortia, compromising the continuity of water supply. Since 2012, the system has experienced progressive deterioration: hundreds of wells in the Al-Jafara, Al-Hasawna, and Al-Sirir-Tazerbo networks have been taken out of service, while repeated attacks and blockages at pumping stations - such as those in the Hasawna area between 2017 and 2020 - interrupted supply to Tripoli and other cities multiple times, leaving millions of people without water for days. These events highlight how control over the GMR has become a strategic instrument of local power: those who operate the system’s valves exert direct influence over the survival of urban and agricultural regions along the coast.

To mitigate the effects of the crisis, international agencies such as UNICEF, UNDP, FAO, and the European Union have initiated emergency interventions aimed at supporting maintenance, improving technical management, and reducing the humanitarian impact of interruptions. Nevertheless, the GMR remains only partially operational: infrastructure degradation, irregular maintenance, and security gaps continue to compromise its stability, particularly in the Fezzan and central Tripolitania regions.

Born as a symbol of water emancipation and national modernization, the GMR today stands at the center of a paradox: a vital yet fragile network, dependent on finite water resources and vulnerable both to infrastructural decay and the fragmentation of political authority.

The Future of the Great Man-Made River

The Great Man-Made River (GMR) today stands at a historic crossroads. It is no longer merely a water infrastructure project but serves as an indicator of the Libyan state’s capacity to function as a cohesive entity, capable of planning, managing, and cooperating within a context of institutional fragmentation. The future of the GMR lies at the intersection of hydrogeological sustainability, national governance, and technological innovation, outlining a complex and continuously evolving scenario.

The first critical challenge concerns the environment and resource availability. The system relies on fossil aquifers, formed in remote climatic epochs and therefore intrinsically non-renewable. Extraction rates, exceeding the natural recharge capacity, risk, according to numerous estimates, compromising the main Fezzan and Kufra basins within a few decades, exacerbating salinization and seawater intrusion in coastal aquifers. This perspective makes water resource management an existential issue for urban and agricultural communities, requiring urgent adoption of integrated policies for sustainable management, balanced withdrawal, and diversification of sources.

From a technological standpoint, the GMR’s future calls for a comprehensive reassessment of Libya’s national water supply model. After decades of near-exclusive dependence on non-renewable groundwater, Libya must now diversify its sources, incorporating desalination as a structural component of its water strategy. While previously constrained by economic and infrastructural limits, recent advances in reverse osmosis technology and energy efficiency now make the installation of modern coastal plants more feasible. Observers and international agencies emphasize that a gradual integration of the GMR with a coastal desalination network - spanning Tripoli, Misurata, Benghazi, and Tobruk - could reduce reliance on fossil aquifers and increase the resilience of the national water system.

Institutional planning represents another crucial element. The GMR is a test of the Libyan state’s ability to ensure continuity of essential services and infrastructural security. Political fragmentation and weak central structures have demonstrated the vulnerability of a system of this scale in the absence of stable and competent governance. The current division of responsibilities among the General Water Authority (GWA), Ministry of Water Resources (MWR), and Great Man-Made River Authority (GMRA) diminishes the system’s operational and strategic effectiveness. To address these challenges, several international programs aim to strengthen coordination functions among these agencies, clarify the division of responsibilities, and enhance financial autonomy, technical expertise, and cooperation capacity with local municipalities. Such institutional strengthening is essential for ensuring a more transparent, coordinated, and politically secure water management system.

Finally, the regional dimension plays a strategic role. The GMR draws from aquifers shared with Egypt, Sudan, and Chad; their management requires a multilateral approach based on cross-border cooperation. While Libya’s current unilateral exploitation is legally justified under territorial law, it could generate future tensions. A regional agreement for sustainable management of fossil water would ensure greater stability and cohesion, transforming a potential source of conflict into an opportunity for water diplomacy.

From this perspective, the GMR is not merely a collection of pipelines and wells but a strategic, political, and symbolic node: its survival will depend on balancing technological innovation, resource sustainability, and the Libyan state’s capacity to rebuild unity, governance, and long-term vision.

___________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________

Bibliography

Abugdera, A. F. (November 2024). General Features of the Libyan Strategy for Water Resource Management. AlQalam Journal of Medical and Applied Sciences. https://doi.org/10.54361/ajmas.247430

Al Jazeera. (May 2019). Libya: Armed group cuts off water supply to Tripoli. https://www.aljazeera.com/news/2019/5/21/libya-armed-group-cuts-off-water-supply-to-tripoli

Altaeb, M. (December 2021). Desalination in Libya: Challenges and Opportunities. Middle East Institute.https://www.mei.edu/publications/desalination-libya-challenges-and-opportunities

Altaeb, M. (August 2022). What’s Next for Libya’s Great Man-Made River Project? Middle East Institute (MEI).https://www.mei.edu/publications/whats-next-libyas-great-man-made-river-project

Altaeb, M., & Sheira, O. (June 2024). A Survey of Libya’s Environmental Challenges. Mediterranean Policy (LUISS).https://mp.luiss.it/archives/a-survey-of-libyas-environmental-challenges/

Badran, W. (August 2021). Libya: The Man-Made River that Quenches the Sahara’s Thirst. BBC Arabic.https://www.bbc.com/arabic/middleeast-58370031

Brika, B. (2018). Water Resources and Desalination in Libya: A Review. Proceedings, 2(11), 586. https://doi.org/10.3390/proceedings2110586

Britannica. (n.d.). Great Man-Made River. https://www.britannica.com/topic/Great-Man-Made-River

Caliber.az. (August 2024). Libya’s Great Man-Made River Exposes Water Crisis Amid Political Instability. https://caliber.az/en/post/libya-s-great-man-made-river-exposes-water-crisis-amid-political-instability

Climate Risk Profile: Libya. (2025). The World Bank Group.https://climateknowledgeportal.worldbank.org/sites/default/files/country-profiles/16998-WB_Libya%20Country%20Profile-WEB.pdf

EPCM Holdings. (2022). History and Long-Term Fate of the Great Man-Made River in Libya. https://epcmholdings.com/history-and-long-term-fate-of-the-great-man-made-river-in-libya/

International Organization for Migration (IOM). (October 2022). UN Climate Change Fact Sheet: Libya. https://libya.iom.int/sites/g/files/tmzbdl931/files/documents/UN%20Climate%20Change%20Factsheet%20Libya.pdf

Kemkhadze, S. (September 2024). Innovating for Water Security and Resilience in Libya. United Nations Development Programme (UNDP). https://www.undp.org/libya/blog/innovating-water-security-and-resilience-libya

Maiar, S. (December 2024). Libya Prepares Final Phase for Giant Man-Made River. A.G.B.I.https://www.agbi.com/opinion/infrastructure/2024/12/libya-prepares-final-phase-for-giant-man-made-river/

Nasar, M. N. (2015). Survey of Sustainable Development to Make Great Man-Made River Producing Energy and Food. Current World Environment, 10(3). https://doi.org/10.12944/CWE.10.3.05

PERC – Property and Environment Research Center. (March 2011). Libya’s Water Supply: The Great Man-Made River. https://www.perc.org/2011/03/18/libyas-water-supply-the-great-man-made-river/

Petecca, D. E. (March 2025). The Great Man-Made River: Quenching Libya’s Millennia-Long Thirst. Osservatorio Strategico Mediterraneo Allargato. https://osservatoriostrategicomediterraneoallargato.com/2025/03/03/the-great-man-made-river-quenching-libyas-millennia-long-thirst/

Salih, M. T. (December 2021). The Great Man-Made River Project. University of the West of Scotland.https://doi.org/10.13140/RG.2.2.12786.84163

Sümer, V. (August 2017). Reconfiguring the Aquatic Divide in North-East Africa: The Rise and Fall of the Great Man-Made River. ORSAM – Center for Middle Eastern Studies. https://orsam.org.tr/en/yayinlar/reconfiguring-the-aquatic-divide-in-north-east-africa-the-rise-and-fall-of-the-great-man-made-river/

United Nations Children’s Fund (UNICEF). (December 2018). Libya Humanitarian Situation Report – End of Year 2018. https://www.unicef.org/media/76886/file/Libya-SitRep-Dec-2018.pdf

United Nations Children’s Fund (UNICEF). (August 2020). Water Shortage Threatens 4 Million People in Libya. Libya Observer. https://libyaobserver.ly/news/unicef-water-shortage-threatens-4-million-people-libya

United Nations Human Settlements Programme (UN-Habitat). (2014). The State of African Cities: Re-imagining Sustainable Urban Transitions. https://unhabitat.org/state-of-african-cities-2014-re-imagining-sustainable-urban-transitions

United Nations Support Mission in Libya (UNSMIL). (May 2019). UN Humanitarian Coordinator in Libya Strongly Condemns Blockage of the Great Man-Made River Cutting Off Water Supply. United Nations Department of Political and Peacebuilding Affairs (DPPA). https://dppa.un.org/en/un-humanitarian-coordinator-libya-strongly-condemns-blockage-of-great-man-made-river-cutting-off

Zurlo, D. (2020). Beyond Hydrocarbons: Libya’s Blue Gold. Istituto Affari Internazionali (IAI).https://www.iai.it/sites/default/files/iaicom2028.pdf

Abaqua

Via Cassia, 615

00189 Roma (RM)

© 2024. All rights reserved.

Codice Fiscale: 96584590580