Project for the construction of an artesian well in Benin

Filippo Verre - January 31, 2023

* L’immagine di copertina di questo progetto è stata presa dal sito Global Charity Initiative, consultabile al seguente link: https://globalcharityinitiative.org/digging-wells-in-africa-a-waste-of-money-and-resources/

The constant growth of the world population in recent years – especially in sub-Saharan Africa – has made water supply a strategic issue for many nations that find themselves managing complex demographic dynamics. Along with the progressive increase in their inhabitants, many countries are simultaneously experiencing cases of mass urbanization. This factor contributes to making water, a primary good par excellence, a resource to be safeguarded in terms of urban planning.

From a water point of view, the presence of a (growing) multitude of people living in small portions of territory represents one of the most complex challenges that a state administration is called upon to solve. In fact, a double problem often occurs on both the quantitative and qualitative fronts regarding the availability of fresh water. On the one hand, the authorities must provide the water necessary for the daily activities of millions of individuals. On the other, they have the obligation to take charge of delivering to their citizens water of acceptable quality capable of ensuring both the satisfaction of individual needs and an economic-industrial production adequate to the number of residents. This second aspect is not at all marginal, since water, in addition to being the source of life for all living beings, is a resource in all respects and is used in almost all production processes.

According to some reports recently produced by the FAO, the global demand for fresh water doubles every 21 years. This is an important fact that gives us an extremely dynamic picture regarding the water needs of the world population. However, it is necessary to focus on another equally relevant fact. Again according to the FAO, more than 500,000 people die every day throughout the world due to diseases transmitted by contaminated water. Therefore, in the face of a dizzying increase in global water demand, it is necessary to provide water as free as possible from pathogens that are dangerous to human life. To do this, it is appropriate to increase the availability of water infrastructures capable of satisfying the growing need for water from a socioeconomic point of view.

Benin: a growing water market

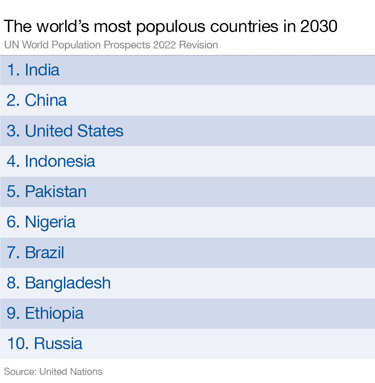

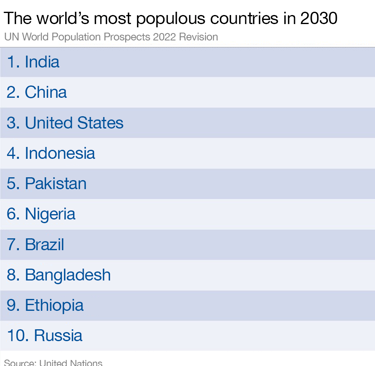

Benin, a medium-sized sub-Saharan state overlooking the Gulf of Guinea, is the ideal “candidate” to receive future funds for the improvement of its water infrastructure. It has a not particularly significant territorial extension – equal to 112,620 km² (just over a third of Italy) – and a population of around 12.4 million. At a demographic level, Porto Novo[1] has been growing progressively for about two decades without, however, reaching the dizzying peaks of neighboring Nigeria, a true colossus in terms of population. Consider, in this regard, that Abuja is currently in sixth place in the global ranking of nations with the largest populations with projections of clear growth over the next few decades[2].

Fig. 1: Lista dei Paesi più popolosi al mondo nel 2030

https://www.weforum.org/agenda/2022/08/world-population-countries-india-china-2030/

Fig. 2: Geolocalizzazione del Benin

https://hadithi.africa/know-benin/

The demographic explosion that characterizes Nigeria - but also other African nations, just think of Egypt and Ethiopia for example - requires that the construction of water works be planned in a climate of urgency and immediacy. On the other hand, the multitude of people subjected to stress or, in many cases, to real water supply crises means that the various international organizations operating in those countries adopt an emergency-oriented approach. There is no room, in this sense, for water works conceived on the basis of reasoned urban planning, or projects aimed at obtaining medium-long term results. What matters, unfortunately, is the resolution of clear water crises, exacerbated by the excessive growth of the population and disorganized mass urbanization.

The situation in Benin, in fact, is significantly different. As mentioned, population growth is constant but not explosive; this allows us to conceive water works not with an emergency approach but with a strategic one, compatible with the needs of the Porto Novo government agenda. In other words, in this small sub-Saharan state it is possible to realize projects that can bring an effective lasting benefit to the local population, whose water needs can be not only satisfied but also, in a certain sense, predicted. This last aspect is very relevant from a teleological perspective, since a correct predictive analysis can make the difference between a good project and an excellent project, between a temporary measure and a medium-long term one, between the construction of an emergency work or a strategic infrastructure that brings trans-generational benefits.

Among the factors to take into consideration when building water works in Benin, there is undoubtedly the climate. As can be seen from Fig. 2, this country is located not far from the equator; this guarantees abundant humidity, especially in the southern regions. In fact, near the coasts, annual rainfall is on average 1,300 mm, with peaks of even 1,500. Interesting data, which certify the presence of significant water resources due to constant rainfall. In this regard, the rainy season occurs from April to the end of July, with shorter and less intense rainfall from the end of September to November. From December to April, the so-called dry period occurs, characterized by the presence of the hot Saharan wind called Harmattan [3], during which a veil of fine dust hovers over the country for several weeks, the vegetation turns reddish-brown, the grass dries up and the sky is overcast [4].

The continuous rainfall that occurs on Beninese territory means that Porto Novo can count on over two billion m³ of water per year from the so-called surface waters, that is, watercourses, lakes, wetlands[5]. The latter are regularly supplied with abundant rainwater. To this must be added the approximately eleven billion m³ of water that are found in the subsoil of Benin, in particular in underground waters, artesian and phreatic aquifers. Overall, therefore, the water resources available to the Beninese are over thirteen billion m³, a truly considerable figure for a population, as we have seen, of small demographic size settled on a decidedly small territory.

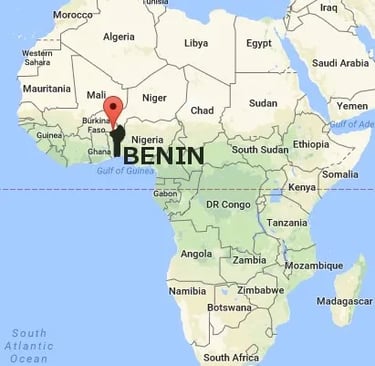

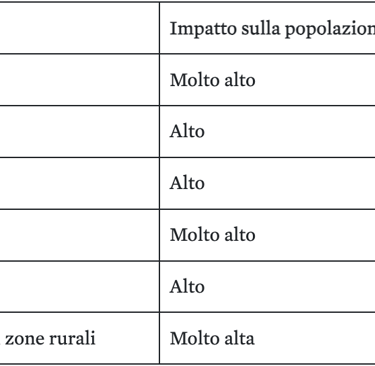

Despite an unexpected abundance of fresh water present both in its subsoil and due to the high volume of rainfall, Benin is a State in which water stress represents a very serious problem. The small population, mostly agricultural, does not have access to reliable and clean sources of supply, in addition to experiencing from time to time cases of worrying water pollution that make the existing water unavailable for domestic, agricultural and industrial uses. As shown in Table 1, from a hydro-environmental point of view, Porto Novo finds itself having to resolve a series of issues that are certainly not easy.

Tab. 1: Principali questioni idriche del Benin[6]

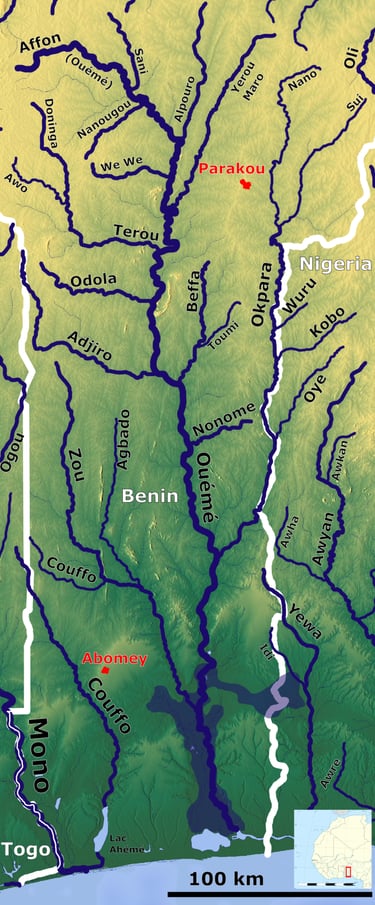

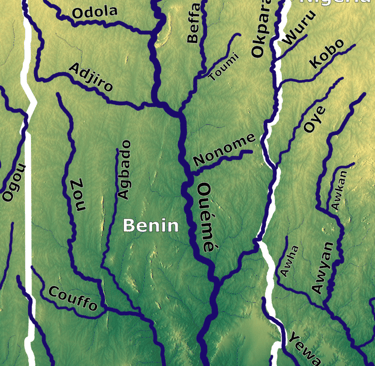

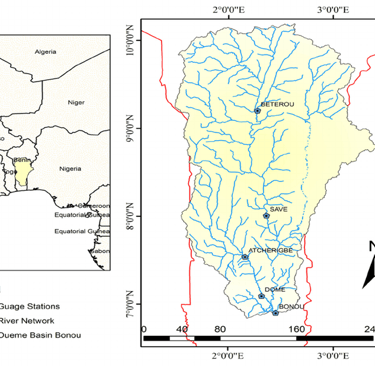

The main problem regarding the availability of water in Benin is undoubtedly the lack of an adequate sewage system, especially in rural areas. This situation means that waste water, often characterized by a high bacterial concentration and pollutants, is not adequately disposed of or directed into special basins. On the contrary, water waste from both domestic and productive uses is very often poured into the numerous streams and waterways from which, subsequently, the Beninese themselves usually draw their supplies. In this sense, the high number of rivers (as can be seen from Figs. 3 and 4) that crisscross the entire national territory under the jurisdiction of Porto Novo represents more of a disadvantage than a positive element. The widespread diffusion of waterways, combined with the homogeneous and worrying absence of sewers, means that wastewater loaded with pathogens circulates at all latitudes of the country, ensuring the spread of diseases and the presence of various unhealthy environments.

The second critical element regarding the water situation in Benin is precisely related to the high pollution of the numerous sources on national soil. In this regard, there are various harmful substances present in Beninese waters. As previously mentioned, the substantially agricultural nature of the population - but also of some economic-productive sectors - of Benin means that agriculture plays a key role in the productive basket of Porto Novo. To increase food supplies, the government has over time encouraged the use of fertilizers and herbicides. This has undoubtedly increased agricultural production but has also increased the rate of chemical waste. Hydrochloric acid, sulphur, phosphoric acid and other highly polluting substances have been found along the course of the Ouémé River[7], whose vast water basin covers approximately 50% of the entire national territory of Benin. Pollutants have also been found in the Niger River, a large transboundary watercourse which, along its entire length (approximately 4,160 km), also passes through the north-eastern side of Benin on the border with the Nigerien state.

Fig. 3: Il corso del fiume Ouémé, il più importante corso d’acqua del Benin, con tutti i suoi affluenti https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Ou%C3%A9m%C3%A9_River#/media/File:Oueme_OSM.png

Fig. 4: Bacino idrico del fiume Ouémé

https://www.researchgate.net/publication/283619104_Non-Stationary_Flood_Frequency_Analysis_in_the_Oueme_River_Basin_Benin_Republic/figures?lo=1

Along with the high level of water pollution, Porto Novo suffers from the lack of Water Purification Plants – WPP (water purification plants). The high bacterial concentration and harmful substances present in Benin’s fresh water sources could be limited through the progressive diffusion of plants capable of purifying water. In fact, as already mentioned, Benin’s main water problem lies in the quality of the available sources. However, plants of this size have significant construction costs for a developing nation like Benin. Furthermore, once built, WPPs require highly specialized personnel to operate at full capacity. At present, it should be noted that both in terms of construction costs and local personnel capable of operating the facilities, Porto Novo could have difficulties in integrating WPPs into its water system.

Water regulation attempts in Benin: an overview

Polluted water sources represent a very serious damage for a State and a community. Dirty water, especially if used by many citizens who are unable to use clean sources, is a harbinger of serious diseases that have a high social cost. In the case of Benin, it should be noted that approximately 15% of the population regularly draws water from the numerous lakes and rivers spread throughout the country. This means that over 1.8 million Beninese, especially in rural areas, are daily subjected to the attack of pathogens that could cause serious disorders. Hepatitis, cholera, dysentery, diarrhea and typhoid are just some of the diseases that are highly prevalent in the case of polluted water.

In order to try to reduce as much as possible the effects of water pollution on its socioeconomic system, Porto Novo has adopted, over time, a series of regulatory standards. In 1998, for example, the government adopted Integrated Water Resources Management (IWRM), as a priority approach for the sustainable management of the so-called “blue gold”. This measure was a consequence of the results, so to speak not excellent, of an external report on Benin's strategy for water management, judged deficient especially in terms of environmental sustainability and reuse of the resource. The report, presented in February 1998, recommended in its final parts the adoption of IWRM to improve water management in the state overlooking the Gulf of Guinea[8].

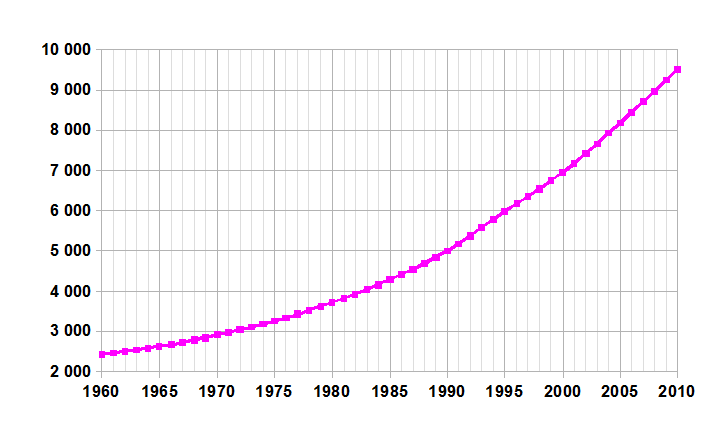

Although the quality of water available to Beninese citizens has not improved significantly following IWRM, it should be noted that in the early years of the new millennium Porto Novo has implemented significant organizational reforms regarding energy supply and water management. Until 2003, responsibility for urban water supply and sanitation services was entrusted to the Société Béninoise d'Energie Electrique (SBEE). Subsequently, much of the electricity sector was privatized, while the urban water sector remained public and was supplied by the Société Nationale des Eaux du Bénin (SONEB). The state thus lost its monopoly on energy supply while retaining control of water supply (in urban areas); new players entered the game with bold objectives: to provide more energy and (clean) water to the growing Beninese population, which in 20 years (1990-2010) went from 5 to about 9.7 million individuals.

Fig. 5: Andamento demografico del Benin tra il 1960 e il 2010[1]

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Demographics_of_Benin#/media/File:Benin-demography.png

In rural areas, the Directorate General of Water (Direction Générale de l’Eau – DG-Eau) became responsible for supervising and coordinating the supply of drinking water. However, despite good intentions, the presence of multiple institutional entities weighed down and slowed down the organizational machine, contributing – initially – to not improving the conditions of the water resource either in terms of quality or quantity.

In the two-year period 2005-2007, in Benin the percentage of infant mortality under 5 years of age was very high: 15.6%. This data portrayed an alarming reality, in which water pollution contributed to the spread of diseases and unhealthy environments. In the Strategic Document for Growth and Poverty Reduction (DSCRP) of the two-year period 2007-2009, the government therefore set as its main objective safer access to water. This was based on the assumption that better management of water resources was the key to national economic growth and development. Following a water bill submitted to Parliament in July 2007, in early 2009 Porto Novo adopted an innovative measure focused on the proper use of the many water resources present in its territory. The pillars of this act, whose objectives are still largely pursued by Porto Novo today, can be summarized in the following points:

Continuous monitoring of drinking water throughout the country in both urban and rural areas.

Providing local authorities with facilities for monitoring and purifying drinking water.

Gradual transition from an intermittent to a continuous water supply system to avoid widespread contamination caused by a non-performing water supply.

Renewal of old, rusty and no longer performing pipes in the water distribution network.

Increased spacing between sewers and drinking water supply lines to avoid cross-contamination.

Adoption of strict laws to monitor the quality of drinking water.

Use of public awareness campaigns to educate the population on the importance of safe drinking water.

Essentially, the main objective pursued by the Beninese authorities with the DSCRP was to improve the quality of water available to citizens. To do so, Porto Novo placed great emphasis on the sanitation aspect associated with water resources. In this respect, this plan was pursued through a series of projects encompassed in the generic expression of Programme d’Assistance au Développement de l’Eau et de l’Assainissement en milieu Rural – PADEAR (Programme of Assistance for the Development of the Water Supply and Sanitation Sector in Rural Areas). Many international partners were involved by Porto Novo; Specifically, we should mention the Danish International Development Agency – DANIDA (active in Benin for almost twenty years from 1992 to 2010[10]), the Agence Française de Développement (which participated in a three-year project from 2005 to 2008 with non-repayable contributions of approximately 22 million dollars[11]), several Dutch companies (active between 2007 and 2011 involved in projects for the supply of water networks in rural areas[12]) and two large German energy agencies, the Deutsche Gesellschaft für Technische Zusammenarbeit (GTZ) and the German Development Bank – KfW Bankengruppe (KFW)[13].

Fig. 6: Acque inquinate del Lago Nokoué, Benin (2019)

https://www.globalnature.org/en/threatened-lake-2019

As shown in Fig. 6, progress in purifying Beninese waters is very slow. In 2019, Lake Nokoué, located in the southern part of the country not far from the coast, was still in difficult conditions. Waste, dirt, sewage and other waste material were present in various forms in a water basin that had been rendered unusable. In fact, making millions of m³ of highly polluted water usable is far from easy. Despite the support of international partners and national authorities capable of carrying out important structural reforms over time, the timescales required to achieve satisfactory results are long. In this regard, we note the financial support provided by the World Bank which, since 2003, has supported Porto Novo's efforts to improve the quality of its water resources through the so-called Poverty Reduction Support Credits (PRSCs). The first PRSCs (2004-2005 and 2005-2006), allocated as part of poverty reduction projects, provided 50 million dollars to Benin, also to be used for water efficiency[14].

In line with the ambitious objectives set for the two-year period 2007-2009, starting in 2012 Benin has focused heavily on decentralization, with the aim of providing rural areas with all the tools necessary to achieve positive outcomes. Over time, DG-Eau has established its headquarters (Provincial Water Divisions) in 11 provinces, increasing its presence even in remote areas, where 77 agencies are active in as many municipalities. The results were not long in coming, as an ever-increasing number of Beninians can now (2023) count on cleaner and more constant water resources. Of course, there is still a long way to go to make Benin a water-secure nation. Nonetheless, credit must be given to the authorities of Porto Novo who have inaugurated, for a couple of decades now, a clear turning point in the protection of their waters.

Also with regard to the policy focused on decentralization, it is worth mentioning the great support offered by the World Bank to Benin projects. Based on the Water and Sanitation Program (WSP), promoted precisely by the World Bank, Porto Novo has been able to benefit from numerous projects whose aim was to improve the water supply in the rural areas of the country. One of the pillars of the WSP, in fact, concerns the development of areas distant from inhabited centers, traditionally less industrialized and, consequently, more subject to negative phenomena such as stagnation, lack of opportunities, mass emigration and so on.

Artesian wells: a valid tool to combat water stress in Benin

To realize the significant results achieved over the years, it would be desirable for Porto Novo to increase its hydraulic infrastructure both numerically and qualitatively. In this regard, there are two possible paths: building more wells or equipping itself with a modern water filtration and purification system capable of making the millions of m³ of water usable that are in fact unavailable due to the aforementioned problems related to pollution. Concretely, the construction of a well represents a very valid option both in the short and in the medium/long term. As mentioned above, in fact, purification plants would be equally valid but require high initial costs and highly specialized personnel capable of operating them. These characteristics, which represent considerable obstacles, are not found with regard to wells.

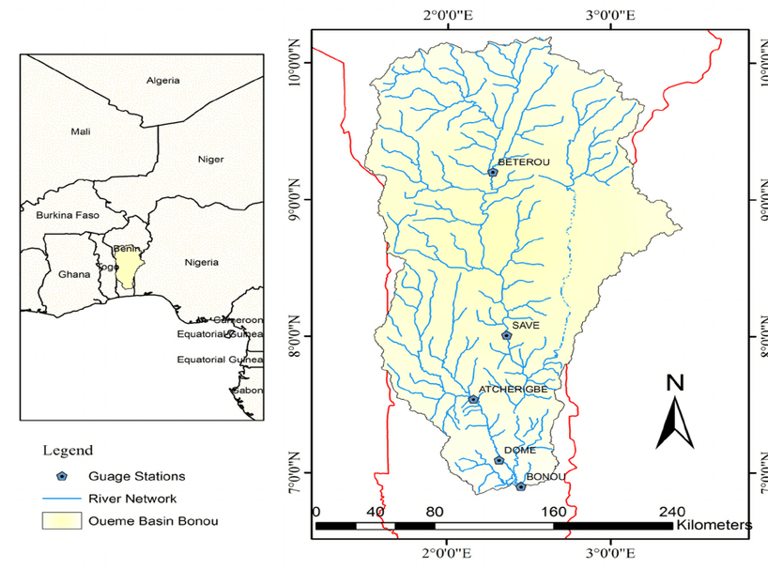

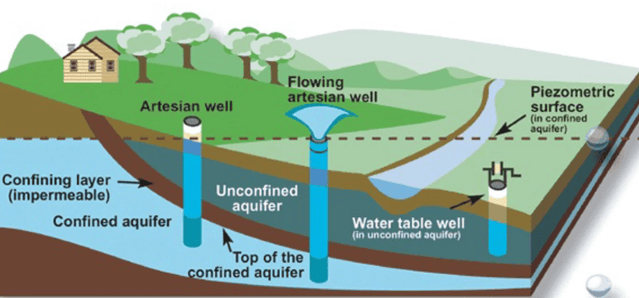

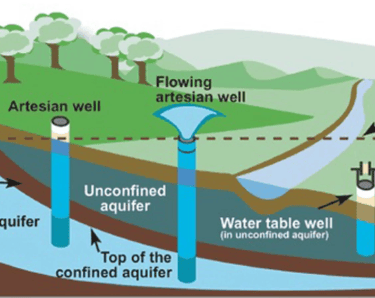

Specifically, the creation of a network of artesian wells is considered useful. This solution would ensure the water supply of isolated houses or in places where the water network is characterized by shortages and malfunctions, as unfortunately still happens systematically today in various parts of Benin. The artesian well is very well suited to the hydrological characteristics of this small African nation. In fact, it is often built in places rich in underground water where a particular mechanical force is not necessary to extract the resource from the subsoil. On the contrary, this type of well is usually designed in places where the water flows naturally from the so-called "artesian" aquifers [15]; therefore, there is no need to use means such as submersible pumps, necessary to facilitate the emergence of water on the surface. Artesian wells perforate the upper part of the aquifer and cause the water to rise upwards, up to the static level of the aquifer itself. At that point, then, the water flows from the ground without further pressure.

Fig. 7: Schema di realizzazione di un pozzo artesiano

https://valleywaternews.org/2019/07/11/what-is-an-artesian-well/

The artesian well is usually small in diameter and deep, made by means of drills mounted on trucks or crawlers. The depth we are talking about is around 100 meters and the water that flows to the surface is often drinkable and ready for use without any particular purification procedures. One of the most important characteristics of wells of this type is that you can choose the points of the aquifer to seal and those to leave free. In fact, if the well is used to irrigate fields, it will be necessary to capture all the aquifers to increase the depth of the well, while if you need a well for domestic use, you must choose the aquifers that have a higher quality and lower risk of pollution. In essence, given the rural characteristics of Benin, it is believed that the spread of wells can help make the water supply safer for tens of thousands of families.

For construction and maintenance, the artesian well would be preferable to other works, such as, for example, the phreatic well. The latter is a particular type of well that draws water from an aquifer, called phreatic, containing water not under pressure, as instead happens in the artesian one where the water accumulates a strong pressure due to the impossibility of gushing out. Even though it operates in a usually shallow aquifer (20 meters), the phreatic well cannot extract water without the aid of submersible pumps. For this reason, this well is often quite massive even if it operates at less significant depths than the artesian ones, which can reach, as we have seen, even several dozen meters. The presence of submersible pumps means that from a maintenance point of view the phreatic well requires greater efforts than the artesian one. Furthermore, if in terms of expenditure both hydraulic works are all in all on the same level with a higher live outlay for the artesian (6,000/7,000 for the phreatic well and 8,000/9,000 euros for the artesian well[16]), from a functional point of view there are notable differences. In fact, artesian wells ensure a greater flow of water compared to phreatic wells and, in addition, guarantee a continuous and constant yield, moreover without mechanical tools. Therefore, the artesian well is certainly the best solution for those who need large quantities of water (whether for civil, agricultural or industrial use). The water from these wells, among other things, can be fed into aqueducts and to supply fire-fighting systems.

Fig. 8: Immagine di un pozzo freatico

https://www.pgcasa.it/articoli/spurghi-fognature-e-fossa-biologica/pozzo-freatico-tutto-quello-che-c-e-da-sapere__13301

Conclusion

Benin is a dynamic developing nation where, in recent years, much has been done to secure a growing number of people from a water security perspective. As seen in this project, the combined effect of the work of international organizations and a national policy attentive to the water needs of its citizens has led to important steps forward in terms of water security. In light of this, it is necessary to continue on the path traced in 1998 following the launch of the so-called Integrated Management of Water Resources. A true turning point, this act inaugurated a series of political choices that have progressively freed hundreds of thousands of Beninese citizens from the worrying risks associated with water stress.

Given the now consolidated presence of international operators active in the design of hydraulic works, Benin is the ideal candidate to receive funds for water efficiency projects. The country's subsoil, which is extremely rich in water, could be wisely exploited to create a series of artesian wells, especially in rural areas, where sewage systems are scarce. In a first phase, it is therefore recommended to build such hydraulic works to increase the clean water supply in the most remote areas. In a second phase, it would also be desirable to create an integrated network of artesian wells, that is, a system of wells communicating with each other through a network of canals. In this way, the conditions would be created for the widespread diffusion of uncontaminated water resources. Clearly, the assumption underlying the canals remains that of keeping the water as clean as possible. This would be technically feasible, given that the water resource introduced into the interconnected canals would come from the artesian aquifers located several dozen meters underground and not from Beninese lakes and rivers, which are still highly polluted today. To realize this bold plan, however, it is necessary to start from the bottom, that is, to build artesian wells. It is believed that the expected cost for the construction of a single hydraulic work of this type is in the order of 8,000/10,000 euros.

For further inquiries regarding the strategy to be pursued, the costs and the feasibility of the project, AB AQUA is available upon request via our emails:

______________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________

[1] La capitale del Benin è Porto Novo, ingrandita dai Portoghesi fin dal XVII secolo allo scopo di imbarcare gli schiavi africani diretti nelle Americhe. La città più nota del Paese, tuttavia, è Cotonou dove il 23 giugno 2000 venne firmata l’omonima Convenzione bilaterale tra l’Unione europea e il gruppo degli Stati dell’Africa, dei Caraibi e del Pacifico.

[2] La Nigeria, secondo molte stime demografico-statistiche, diventerà il terzo Paese più popoloso del mondo entro il 2050, ovvero “dopodomani” da un punto di vista geo-strategico. Nel 2100, il gigante subsahariano avrà, da solo, più abitanti dell’intera Unione Europea. Per maggiori dettaglia si rimanda a https://www.africarivista.it/nigeria-terzo-paese-piu-popoloso-del-mondo-entro-il-2050/209006/.

[3] Nella lingua italiana Harmattan viene denominato “Armattano”; si tratta di una un vento secco e polveroso che soffia a nordest e ovest, dal Sahara al Golfo di Guinea, tra novembre e marzo. Viene a tutti gli effetti considerato come un disastro naturale a causa del grande quantitativo di polveri che questo vento diffonde nell’aria. L’Harmattan può limitare severamente la visibilità e oscurare il sole per diversi giorni, risultando paragonabile ad una fitta nebbia giallastra.

[4] Per ulteriori dettagli sulla situazione metereologica del Benin si rimanda a: https://www.ijsrp.org/research-paper-0318/ijsrp-p7509.pdf.

[5] Tecnicamente, nell’elenco delle acque superficiali figurano anche mari ed oceani.

[6] Questa tabella è stata elaborata da AB AQUA tramite l’ausilio di dati reperibili sul sito della FAO, delle Nazioni Unite e della Banca Mondiale applicati alla situazione idrica beninese. Per maggiori dettaglia si rimanda ai rispettivi siti delle organizzazioni citate.

[7] Lungo circa 510 km, il fiume Ouémé ha un bacino idrico che copre circa 50.000 km quadrati di territorio, per lo più centrale, e sfocia nel Golfo della Guinea non lontano da Cotonou, capitale economica del Paese.

[8] https://www.ijsrp.org/research-paper-0318/ijsrp-p7509.pdf.

[9] Dati reperibili presso la FAO.

[10] DANIDA, durante i quasi 20 anni di attività in Benin, ha operato in ben 4 dipartimenti: Nel 1992, in partnership con la Banca Mondiale, l’agenzia danese ha svolto lavori nei Dipartimenti di Zou e dell’Atlantico. Successivamente, in base al progetto PADEAR, i lavori sono proseguiti nei dipartimenti di Alibori e Borgou. L’obiettivo di DANIDA è stato di ridurre la povertà nelle zone rurali e di migliorare l’approvvigionamento idrico delle comunità più remote del Paese. Per ulteriori dettagli in merito alle attività dell’agenzia danese in Benin si rimanda a: https://web.archive.org/web/20110719134315/http://www.danidadevforum.um.dk/NR/rdonlyres/67C09687-D240-40FB-A668-B9A8CE079C51/0/WS_ProgDocPhase2.pdf.

[11] L’obiettivo principale francese era quello di contrastare la povertà e di garantire un migliore approvvigionamento idrico secondo adeguati criteri igienico-sanitari. I fondi di Parigi vennero indirizzati al Dipartimento delle Colline, una delle 12 municipalità in cui è suddiviso il Benin. Tra i vari scopi, l’agenzia francese mirava a promuovere la decentralizzazione come approccio amministrativo, onde poter favorire la creazione di adeguate strutture idriche nelle zone più remote del Paese. Per ulteriori dettagli si rimanda al seguente link: https://www.afd.fr/fr.

[12] Gli investimenti olandesi hanno garantito, nel corso del tempo, ad oltre 300.000 cittadini beninesi residenti nelle zone rurali di avere accesso a fonti idriche pulite e sicure. Oltre a ciò, in linea con gli obiettivi igienico-sanitari del PADEAR, il governo del Benin ha ricevuto fondi per l’attuazione di una campagna nazionale incentrata sulla promozione del lavaggio delle mani. Per ulteriori dettagli su questa vicenda in merito alle attività che l’Olanda ha realizzato in Benin si consiglia di consultare il seguente link https://web.archive.org/web/20080517065228/http://larepubliquedubenin.nlambassade.org/cooperation.

[13] Le agenzie tedesche iniziarono a lavorare in Benin dal 1996, in particolare nei distretti di Oueme e Mono. A partire dal 2001, in concomitanza con il lancio del PADEAR ed in linea con i nuovi obiettivi igienico-sanitari di Porto Novo, GTZ e KFW aumentarono le proprie attività fino a lavorare in ben 5 municipalità del Dipartimento di Atakora e in 2 di Donga. Anche in questo caso, l’obiettivo principale del supporto tecnico ed economico tedesco consisteva nell’incrementare la qualità dell’acqua a disposizione delle aree rurali del Benin. Maggiori informazioni sono reperibili al seguente link: http://www.gtz.de/en/weltweit/afrika/benin/1006.htm.

[14] Maggiori dettagli in merito sono reperibili nel sito ufficiale della Banca Mondiale.

[15] Per falda artesiana si intende una tipologia di falda acquifera “confinata”, ovvero caratterizzata da un corpo idrico che occupa un certo quantitativo di rocce e/o sedimenti circondato da materiali impermeabili (ad esempio argilla). L’acqua sotterranea, che non è libera di filtrare attraverso i materiali in cui è confinata, sgorga in maniera naturale verso l’alto una volta che si effettua una pressione anche non meccanica. Il nome del pozzo in questione, dunque, deriva proprio dal nome della falda da cui si preleva la risorsa idrica.

[16] Queste cifre vengono calcolate in base alla circostanza di realizzare un’opera idraulica in Benin. Ciò comporta, infatti, maggiori spese per trasporto del materiale e degli addetti ai lavori in Africa subsahariana. In Italia il costo per entrambi i pozzi sarebbe ridotto.

Abaqua

Via Cassia, 615

00189 Roma (RM)

© 2024. All rights reserved.

Codice Fiscale: 96584590580