Saudi Arabia's Water Policies

Filippo Verre - November 28, 2021

* L’immagine di copertina di questo report è stata presa dal sito Fanack Water, consultabile al seguente link: https://water.fanack.com/saudi-arabia/

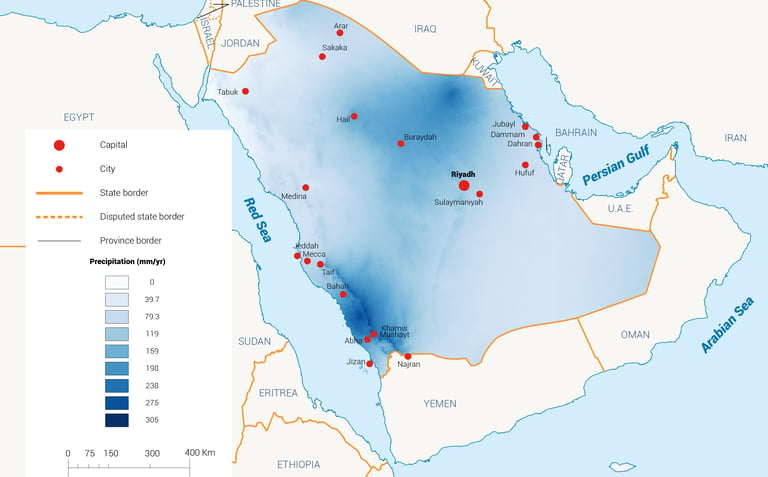

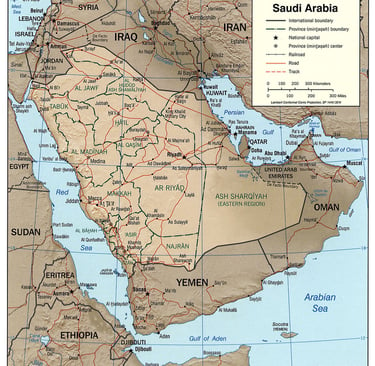

A huge desert land and abundant oil. These are the first characteristics that usually come to mind when referring to Saudi Arabia. To a certain extent, both of these pieces of information are correct, even if incomplete. It is in fact one of the most inhospitable countries on the planet in terms of climate, with an average annual temperature of about 32 degrees Celsius and very low rainfall rates, between 50 and 75 mm per year. In terms of oil, the large Arab Kingdom has about a quarter of the world's proven crude oil reserves and is the main producer and exporter. These facts and figures are incontrovertible, in the public domain; for a long time they have had a stereotyped impact on the notions of geography relating to the kingdom of Saud, considered by many as a large, mostly inhospitable territory that owes most of its political and financial fortunes to the undoubted wealth of its subsoil. However, not everyone knows that the subsoil of Saudi Arabia is rich in "black gold", but also in water. Yes, the Saudi groundwater contains billions of cubic meters of water, a legacy of millions of years ago when the entire Arabian peninsula was a huge green expanse where forests, lakes and rivers were widespread.

For some years now, Riyadh has achieved unexpected agricultural and food self-sufficiency. In recent times, the Saudis have even become net exporters of agricultural products. The reason for such a result, in some ways astonishing, is largely due to the water policies that have been implemented over the last few decades. The strategies adopted, especially focused on large-scale desalination and the massive exploitation of ancient aquifers, have in fact brought about undoubted benefits on both a social and economic level. Nevertheless, many questions arise regarding the sustainability of these water policies, which are geared towards achieving medium- to short-term effects with little long-term interest.

Water self-sufficiency and agricultural exports: a Saudi success

According to various reports, by 2050 the current population of Saudi Arabia, which currently numbers 34 million individuals, will be around 77 million (1). These forecasts have been known since the early 2000s, when the population of the Kingdom began to grow with a certain regularity. This has placed the Saudi royal house in front of a dilemma: continue to import agricultural products in exchange for oil, which was done more or less until the early 1990s, or invest in research into more sustainable and self-sufficient methods of agricultural production. Until the second half of the 1980s, the Saudis were net importers of almost all (80%) of the food necessary to sustain their population. The main reason for this was the lack of substantial alternatives. Desalination was struggling to establish itself and intensive exploitation of aquifers began only in the mid-1980s.

Aware of the demographic and social challenge that awaited the country in the following years, the Saudi royals began over time to change course and lay the foundations for food self-sufficiency. The first step in this direction was the adoption of a real water policy that was able to guarantee satisfactory results in a not too long time. And in fact, at least according to a first reading of the data, Riyadh is currently not only totally self-sufficient, but is also able to guarantee a respectable agricultural export to a growing number of countries, both in Africa and Asia.

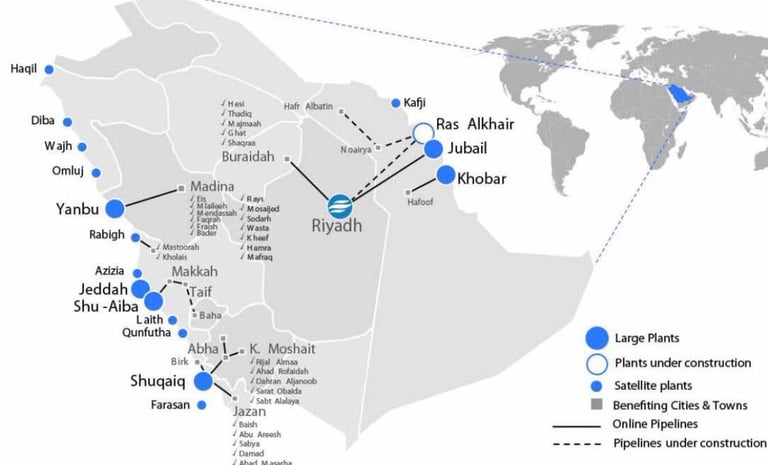

The first pillar of Saudi water measures was the large-scale use of desalination plants. The abundance of sea water guarantees the Arabian Peninsula, being surrounded by the sea in three large stretches, a wide availability of marine water resources. Once industrial desalination became a widespread measure in the global context, Riyadh made extensive use of it. This situation is well photographed by the numbers. The Saline Water Conversion Corporation (SWCC), a Saudi company founded in 1974, is the largest seawater desalination company in the world. SWCC has about 30 large desalination plants operating throughout the country, has over 4,000 kilometers of aqueduct, employs about 10,000 Saudis, is the second largest electricity provider in the Kingdom and has a commercial value of over 20 billion dollars.

Fig. 1: Logo della Saline Water Conversion Corporation

Fig. 2: Principali dissalatori in Arabia Saudita

Impressive numbers that demonstrate how important desalination is in the socio-energy dynamics of the Kingdom. The plants managed by SWCC produce more than three billion cubic meters of drinking water per day, supply 70% of the water needs of all Saudi cities and also play a primary role in the use of non-saline water resources in national industry. In essence, the Saline Water Conversion Corporation is a giant that has allowed Riyadh to count on a lot of desalinated water used in the most diverse sectors.

While SWCC has had an impact mainly in cities and in the production of electricity, the exploitation of the rich Saudi aquifers has instead guaranteed the Kingdom an additional water source to be used especially in the countryside. The second pillar of Riyadh's policies regarding water is precisely the use of groundwater to find the precious liquid and use it in the irrigation phase. The first large underground water deposits were discovered in the late 1960s, when some oil companies were commissioned by the government to explore the subsoil in search of crude oil. In addition to the latter, the technicians found vast underground areas in which water was abundant. On average, the aquifers from which it was possible to draw water had an estimated depth of between 250 and 450 meters (2); this means that it was possible to use the trapped water with the help of simple wells. By virtue of this important discovery, many small and medium-sized wells were built from which it was possible to obtain water without particular engineering techniques.

Initially, the discovery of vast aquifers created some uncertainty in Saudi politics. After having identified an unexpected and rich water source, it was necessary to have clear ideas on how to use it, especially in view of agricultural production. Until a few decades ago, dates were the “star” product of the Saudi agricultural sector. This is because it is a palm fruit that requires little water to grow and that guarantees an important energy supply. After the discovery of underground water deposits, the “rules of engagement” had changed, the resources that Riyadh could count on had increased exponentially. This required real agricultural planning, something that had never occurred since the origins of the Kingdom due to the very limited water reserves that Saudi farmers could count on.

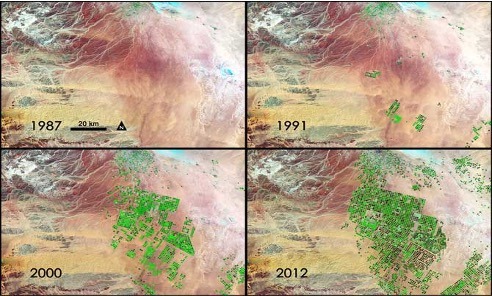

After a few years of uncertainty, the royal family decided to invest not so much in the production of some specific agricultural products but in the use of a specific irrigation technique: Center Pivot Irrigation (center pivot irrigation). Invented in 1940 by the American farmer Frank Zybach, this method uses a mechanical system consisting of a mobile tube, rotating around a fixed point, from which water comes out with the sprinkler irrigation technique. In this way, it is possible to circumscribe the land that one wants to cultivate and to use moderate water resources to produce a specific agricultural product. Saudi Arabia has made extensive use of this technique to diversify its food production, avoiding concentrating on the few products that would have been grown with traditional methods. As can be seen in Fig. 3, since the late 1980s, Riyadh has made extensive use of Center Pivot Irrigation in order to guarantee a growing population a variety of agricultural products.

Fig. 3: Diffusione della Center Pivot Irrigation in Arabia Saudita dal 1987 al 2012 https://pagina22.com.br/2012/04/03/sauditas-extraem-agua-fossil-para-plantar/

To use a central pivot, the terrain must be reasonably flat or undulating. From this point of view, the Arabian Desert is perfect because it is mainly a very large semi-flat area with some mountainous reliefs, especially in the western part. These reliefs (the Hejaz mountains), among other things, prevent African currents from penetrating into the Arabian Peninsula and in fact constitute a natural barrier that severely limits rainfall.

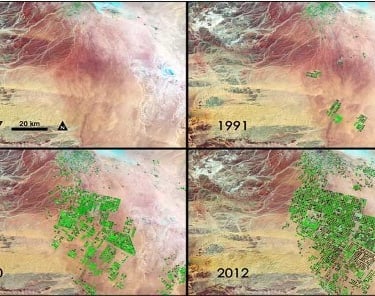

Fig. 4: Penisola Arabica vista dal satellite con particolare focus su Arabia Saudita https://www.kaskus.co.id/thread/57e37885d9d7707b3a8b4567/15-negara-paling-strategis-secara-geografis-di-dunia/

Fig. 5: Mappa dell’Arabia Saudita con rilevanza sui Monti Hejaz

As can be seen in Fig. 5, the coastal part of the peninsula, that narrow strip of land located between the Hegiaz mountains and the Red Sea, is the most fertile area of the country where almost all the land that can be cultivated with traditional methods is concentrated. The presence of water tables in the north-east and in the southern part has allowed the development of a solid agricultural production.

Center Pivot Irrigation has a very recognizable characteristic: by virtue of the peculiar irrigation technique, the cultivated fields often result in almost perfect geometric circles.

Fig. 6: I caratteristici “cerchi di grano” frutto della Center Pivot Irrigation https://greenbusinesspost.com/arabia-saudita-mostra-que-nao-existe-limites-para-agricultura/

This technique, in addition to ensuring an aesthetically pleasing result, guarantees high rates of production efficiency. For about fifteen years, Saudi Arabia has been completely self-sufficient from an agricultural-food point of view. The discovery and subsequent exploitation of ancient water tables, together with the adoption of Center Pivot Irrigation, have constituted the perfect combination in this sense.

The excellent results in terms of agricultural production have allowed the Saudis to achieve two other important successes. First of all, as already mentioned above, after having satisfied the domestic market, Riyadh is now a reliable exporter of various products, including wheat, milk and dairy products, meat and eggs. This has been favored by the large investments that the government has made to improve rural roads and communication routes that connect ports with agricultural production sites. Not only food goods but also other types of products, such as flowers, are regularly exported from Saudi Arabia to the Horn of Africa and Southeast Asia. Secondly, precisely because of the high agricultural production guaranteed by the factors we have mentioned, the Saudis have been able to change the eating habits of their population. In some respects, especially at a socio-anthropological level, this is an even more important result than the agricultural exports that have distinguished Riyadh for some years now. Nowadays, the Saudi diet is made up of plenty of vegetables, milk, eggs, wheat, poultry and various types of meat. All this seems incredible when compared to a few decades ago, when the vast majority of these products were imported from third countries and, consequently, had a cost that only a few families could afford. In the past, the main dishes that could be easily found locally were dates, desert grapes and dromedary meat. Of course, imports introduced other foodstuffs into the Saudi domestic market, so there was still a wide range of choice. However, as mentioned, these were not national products but imported goods. Thanks to new irrigation techniques and the exploitation of the vast water deposits present in its subsoil, Saudi Arabia can now guarantee its growing population a wide range of agricultural products generated entirely within its national borders.

Desalination and exploitation of aquifers: the critical aspects

The results described above achieved by Saudi Arabia in terms of water and food in recent years are clear for all to see. However, in all fairness, it is appropriate to point out a series of critical issues that these bold water policies have caused at an environmental and diplomatic level. First of all, it should be kept in mind that the high use of industrial desalination plants generates high levels of air and marine pollution. To function at the high rates imposed by Saudi policies, the SWCC plants operate day and night using very high quantities of fossil energy. According to some studies, approximately one third of the oil extracted in the country is used in the production of desalinated water (3). This data lends itself to a double interpretation. On the one hand, Saudi Arabia has the fuel needed to run its desalination industry. Being a nation very rich in oil, production costs are reduced because resources that are already in the material possession of the Kingdom are used. If, for example, the crude oil needed to produce billions of cubic meters of water per day were to be imported, production costs would rise exponentially, making the first pillar of Saudi water policy unsustainable and inapplicable.

On the other hand, the massive use of a highly polluting energy source generates a lot of waste that has a serious environmental impact. For example, in 2016 alone, Saudi Arabia released more than 517 million tons of CO2 into the atmosphere, confirming its position as one of the most polluting countries in the global context (4). Desalination plants are largely responsible for this high number of emissions. Furthermore, numerous problems related to pollution are also found at marine level. Brine, a hyper-saline industrial waste resulting from the desalination process, is regularly disposed of in the sea since other disposal methods would make the entire process very expensive. This causes high levels of pollution of marine environments, especially near the coasts and desalination plants. The waste that is dumped in the sea alters the salinity of the water, causing significant damage to marine flora and fauna.

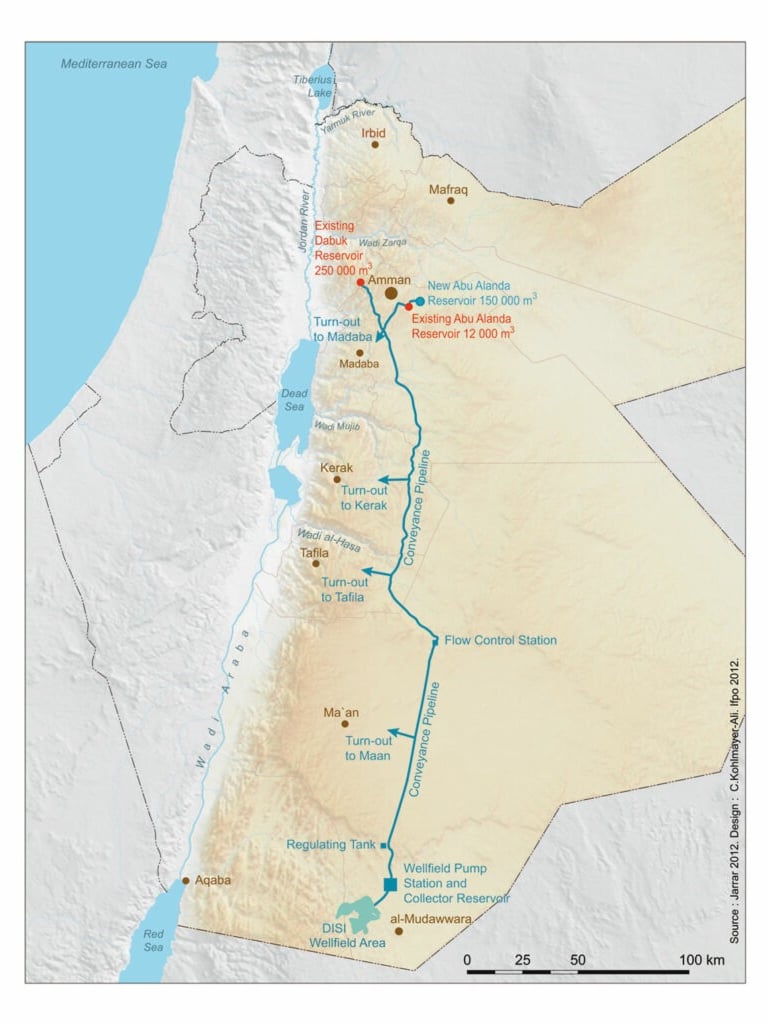

Fig. 8 : Grandezza approssimativa della falda di Disi https://www.flickr.com/photos/zoienvironment/7535447922

Fig. 7: Geolocalizzazione della falda di Disi https://books.openedition.org/ifpo/5060

This technique, in addition to ensuring an aesthetically pleasing result, guarantees high rates of production efficiency. For about fifteen years, Saudi Arabia has been completely self-sufficient from an agricultural-food point of view. The discovery and subsequent exploitation of ancient water tables, together with the adoption of Center Pivot Irrigation, have constituted the perfect combination in this sense.

The excellent results in terms of agricultural production have allowed the Saudis to achieve two other important successes. First of all, as already mentioned above, after having satisfied the domestic market, Riyadh is now a reliable exporter of various products, including wheat, milk and dairy products, meat and eggs. This has been favored by the large investments that the government has made to improve rural roads and communication routes that connect ports with agricultural production sites. Not only food goods but also other types of products, such as flowers, are regularly exported from Saudi Arabia to the Horn of Africa and Southeast Asia. Secondly, precisely because of the high agricultural production guaranteed by the factors we have mentioned, the Saudis have been able to change the eating habits of their population. In some respects, especially at a socio-anthropological level, this is an even more important result than the agricultural exports that have distinguished Riyadh for some years now. Nowadays, the Saudi diet is made up of plenty of vegetables, milk, eggs, wheat, poultry and various types of meat. All this seems incredible when compared to a few decades ago, when the vast majority of these products were imported from third countries and, consequently, had a cost that only a few families could afford. In the past, the main dishes that could be easily found locally were dates, desert grapes and dromedary meat. Of course, imports introduced other foodstuffs into the Saudi domestic market, so there was still a wide range of choice. However, as mentioned, these were not national products but imported goods. Thanks to new irrigation techniques and the exploitation of the vast water deposits present in its subsoil, Saudi Arabia can now guarantee its growing population a wide range of agricultural products generated entirely within its national borders.

Desalination and exploitation of aquifers: the critical aspects

The results described above achieved by Saudi Arabia in terms of water and food in recent years are clear for all to see. However, in all fairness, it is appropriate to point out a series of critical issues that these bold water policies have caused at an environmental and diplomatic level. First of all, it should be kept in mind that the high use of industrial desalination plants generates high levels of air and marine pollution. To function at the high rates imposed by Saudi policies, the SWCC plants operate day and night using very high quantities of fossil energy. According to some studies, approximately one third of the oil extracted in the country is used in the production of desalinated water (3). This data lends itself to a double interpretation. On the one hand, Saudi Arabia has the fuel needed to run its desalination industry. Being a nation very rich in oil, production costs are reduced because resources that are already in the material possession of the Kingdom are used. If, for example, the crude oil needed to produce billions of cubic meters of water per day were to be imported, production costs would rise exponentially, making the first pillar of Saudi water policy unsustainable and inapplicable.

On the other hand, the massive use of a highly polluting energy source generates a lot of waste that has a serious environmental impact. For example, in 2016 alone, Saudi Arabia released more than 517 million tons of CO2 into the atmosphere, confirming its position as one of the most polluting countries in the global context (4). Desalination plants are largely responsible for this high number of emissions. Furthermore, numerous problems related to pollution are also found at marine level. Brine, a hyper-saline industrial waste resulting from the desalination process, is regularly disposed of in the sea since other disposal methods would make the entire process very expensive. This causes high levels of pollution of marine environments, especially near the coasts and desalination plants. The waste that is dumped in the sea alters the salinity of the water, causing significant damage to marine flora and fauna.

_______________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________

(1) Tra il 2015 e il 2020 la popolazione del regno è già incrementata di 5 milioni, a riprova della grande crescita demografica che sta vivendo il Paese da un po’ di anni a questa parte. Per ulteriori dettagli si rimanda a Madeleine Lovelle, Food and Water Security in the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia, in «Future Directions International», 2015. https://www.futuredirections.org.au/publication/food-and-water-security-in-the-kingdom-of-saudi-arabia/.

(2) https://www.tlirr.com/testimonials/jack-king/.

(3) https://www.tlirr.com/testimonials/jack-king/.

(4) https://www.worldometers.info/co2-emissions/saudi-arabia-co2-emissions/.

(5) Già nel 2015 i livelli si erano abbassati, come testimonia questo studio pubblicato dalla ricercatrice Madeleine Lovelle https://www.futuredirections.org.au/publication/food-and-water-security-in-the-kingdom-of-saudi-arabia/.

(6) https://www.waterandfoodsecurity.org/scheda.php?id=110#topscheda.

Abaqua

Via Cassia, 615

00189 Roma (RM)

© 2024. All rights reserved.

Codice Fiscale: 96584590580