Turkey and Water Diplomacy

Filippo Verre - December 11, 2021

* L’immagine di copertina di questo report è stata presa dal sito Engineering Channel, consultabile al seguente link: https://engineering-channel.com/ataturk-dam/

Anatolia has never played a primary role in the development plans devised first in Istanbul and later in Ankara. Since the time of the Ottoman Empire, in fact, that large rocky plateau has been a constant source of concern due in large part to the socio-political tensions that cyclically occurred there. Kurds, Armenians, but also Turkmen tribes, caused major headaches throughout the second half of the 19th century to various sultans and grand viziers, who soon began to consider Anatolia as a "troublesome territory" populated by ethnic groups hostile to the control exercised by the Sublime Porte. Even after 1923, or after the disastrous dissolution of the empire and the birth of the modern Turkish state under the leadership of Mustafa Kemal, Anatolia was the territory that received less attention than other areas of the country that needed infrastructural development. Atatürk himself favored the western regions overlooking the Aegean Sea and the northern part, the so-called Pontus region, bathed by the Black Sea. Immediately after taking power, the Turkish leader expressed his desire to modernize the new republic that arose from the ashes of the empire with what he considered the most strategic infrastructure for those times: the railway. In this regard, in 1933, the tenth anniversary of the foundation of the Republic of Turkey, the Kemalists proudly used to sing at their leader's rallies: "we have woven the entire motherland with iron meshes" [1]. And in fact, according to the data, when Atatürk died of liver cirrhosis in 1938, Turkey had approximately 50% more km of railway than in 1923. In that year, in fact, the km of railway in the whole country were 4,137 and 15 years later 6,149. As many as 2,012 of them had been added [2].

Despite the evident development achieved during the Kemalist government in various regions of the country, as mentioned, Anatolia did not receive particular attention. Of the approximately 2,000 km of railway built from 1923 to 1938, only a few dozen were actually built on site. The reasons were mainly two. First, the steep nature of the territory, characterized by high peaks and deep gorges, certainly did not favor the construction of tracks and platforms. Secondly, Anatolia was (and is) home to millions of Kurds, a strong ethnic minority extremely reluctant to be integrated into the Turkish socio-cultural fabric. An infrastructural development of this territory could have facilitated rebellions against the government of Ankara and worryingly weakened the control exercised by the Turkish authorities on the eastern front. For this reason, therefore, even in the decades that followed the premature death of Atatürk, Anatolia continued to be viewed with ill-concealed suspicion in the halls of power. Basically, it was preferred to leave the large plateau in a state of perpetual underdevelopment in order to prevent potential threats.

This situation began to change starting from the end of the 1970s, when various Turkish leaders and technicians positively re-evaluated the role that Anatolia could play for the entire country. Turgut Özal, a historic Turkish political figure of Kurdish origin and former Prime Minister between 1983 and 1989, was among the first to support a decisive change of direction in this direction. He wisely recognized the intrinsic wealth of this immense and wild territory: water. The Anatolian plateau, in fact, is a gigantic water reservoir that provides water to millions of individuals in various forms. Many large-scale rivers, including the iconic Tigris and Euphrates, originate right in the Anatolian mountains; furthermore, the numerous glaciers present in the region contribute to constantly supplying many sources of fresh water. Not to mention the large deposits of underground water, estimates of which are difficult to quantify but which give a clear idea of how Anatolia is literally one of the largest water reserves in the world. All this has a very significant strategic value, especially if we look at the semi-desert areas of the Arabian plateau and the Near East.

The aim of this report is to analyse Turkish water policy following the major investments that Ankara has made in Anatolia since the early 1980s. Unlike in the past, in fact, the large eastern plateau has become essential in Turkish development plans, not only on the internal front, but above all in terms of relations with its Arab neighbours. Given its dominant geographical position, Turkey plays a leading role in the Middle Eastern region, being the so-called upstream country, that is, the upstream country able to dispose of water resources to the advantage or detriment of downstream countries. By virtue of this, Ankara is a leading player in “water diplomacy”.

Blue gold: Turkey’s wealth lies in Anatolia

The first major Turkish investment in Anatolia in the water sector occurred in the early 1980s. We are talking about the “Southeast Anatolia Project” – Güneydoğu Anadolu Projesi, (hereinafter GAP). It is a massive project that involved the construction of numerous water infrastructures on the Tigris and Euphrates, to be precise 22 dams and 19 hydroelectric power plants. In 1977, the engineering and financial details were defined in concrete terms, while the actual construction began in 1981. Due to its technical size, the GAP is by far the largest Turkish hydraulic infrastructure and one of the largest in the world. The cost of the project, which was initially scheduled for completion in the five-year period 2015-2020, was around 32 billion dollars. This is a very substantial investment for a country like Turkey, which has traditionally never sailed in prosperous financial waters but, on the contrary, has suffered several times from monetary crises due to hasty devaluations of the Lira [3]. Such an important step at a financial level says a lot about how Anatolia has progressively assumed a primary role in Ankara's strategic policies.

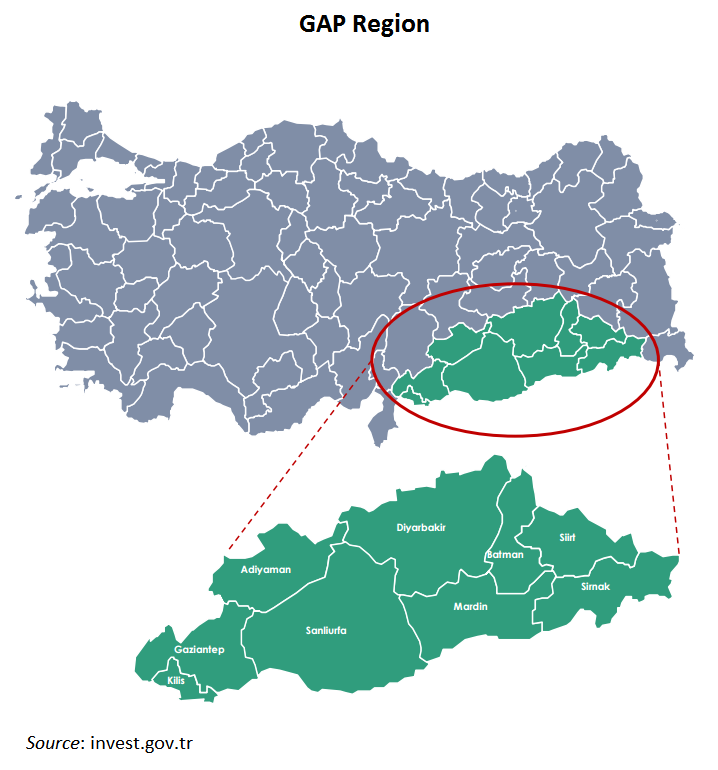

Fig. 1: Il GAP turco e le relative province interessate

Fig. 2: Proiezione del GAP sul territorio turco

In truth, it was Atatürk himself who first theorized the importance of Turkish water development. Since the late 1920s, he had repeatedly expressed his desire to exploit the large water resources that Turkey possessed. As mentioned, Anatolia is extremely rich from this point of view; however, it should be kept in mind that other regions of the country are also well served in terms of water, especially in the western part where large deposits of underground water guarantee a satisfactory water supply for many communities. In those years, however, Turkey was suffering from many problems, including a chronic lack of development in many areas of the country and a conservative society that was not accustomed to modernity. Consequently, despite having understood the water potential that the new republic had, Atatürk was forced to deal with other, much more pressing issues [4]. However, only after the technological advances that occurred during the 1960s and 1970s, Turkish engineers were able to create infrastructure projects that could use water as a source of energy and economic development, as well as a means of sustenance.

The GAP is located in the south-eastern part of Anatolia, covers about 73,000 square kilometers, equal to 9.5% of the Turkish territory, and serves more or less directly 5.5 million citizens, equal to 8.5% of the entire population. As mentioned above, this large hydraulic complex has a dual value for Turkey. On the internal front, Ankara aims to promote Anatolian regional development following the large investments made over the last decades. Despite the GAP, in fact, the region remains extremely underdeveloped in many respects, especially in terms of infrastructure and economy. There are few roads and, apart from the Batman and Gaziantep airports, Anatolia has virtually no connecting structures. As a consequence, even on the production front the situation is not the best. Industry does not have a significant impact on the region [5], which is why the unemployment rate is very high, even by Turkish standards. For this reason, in Ankara's plans the GAP could constitute a sort of flywheel to improve the conditions of a territory historically affected by chronic underdevelopment. The cornerstones of this strategy would reside in the so-called "integrated development", or in the promotion of generalized well-being and wealth following the construction of dams and hydroelectric plants. Once they are operational, these structures require specialized personnel, technicians and workers for maintenance. This means a constant presence on the territory of individuals paid by the State who have to live, eat and presumably have fun in Anatolia. Therefore, as a sort of Keynesian multiplier of Turkish origin, the GAP would bring benefits to the entire region from a production point of view. In fact, if the citizens directly affected by the production of hydroelectric energy are approximately 5.5 million, at an indirect level it is estimated that the induced effects could affect 9.5 million individuals, thus generating a wealth that would otherwise not be possible [6].

Even on the foreign front, the GAP plays a leading role for Turkey, which has always been a Middle Eastern player strongly interested in exercising a significant weight in the regional context. As is known, there are many fronts on which Ankara has been assiduously engaged, both in the Middle East and in North Africa. Just think of the various operations that have followed one another over the last few years in Syria [7] and the brazen Turkish activism in Libya [8]. However, such military unscrupulousness entails great risks in the face of often uncertain results. First of all, in economic terms. As we have seen, this is a country that is not very financially rich, military spending weighs heavily on state coffers, which are increasingly meager after the umpteenth monetary crisis in 2018. In addition, war operations also entail costs in terms of human lives. It should be noted that the Turkish army (Türk Ordusu) is very efficient, numerous [9] and technologically advanced. However, serious incidents often occur that can destabilize even a society accustomed to a climate of tension like the Turkish one. To cite a rather significant case, on February 28, 2020, more than 35 soldiers were killed following a retaliatory raid conducted by the Damascus air force. It was a very heavy toll, a real massacre committed in a single day of fighting.

It is in this extremely thorny context that the GAP fits into Turkish foreign policy. The construction of numerous hydroelectric plants and dams on Anatolian territory has given a great advantage to Ankara, especially with regard to the regulation of water flows to downstream countries, above all Syria and Iraq. The management of the large hydraulic project gives Turkey a power that, very probably, it could not achieve even if it deployed its entire large army on the field. The two Arab nations, in fact, which historically depend heavily on the Tigris and Euphrates for water supplies, have been significantly penalized by the construction of the GAP. It is no coincidence that in the past tensions between Turkey and its neighbors have been very heated due to water issues. With Syria, in particular, they came to the brink of a real Water War when Ankara essentially threatened to "turn off the taps" of the Euphrates if Damascus did not expel Abdullah Öcalan, the historic Kurdish leader and founder of the PKK who had found refuge in Syria since 1979. After a few weeks of diplomatic crisis, relations between the two countries were restored, thus avoiding giving rise to a bloody conflict centered precisely on access to water denied to Syria by Turkey. Following the serious Turkish threat, Öcalan was in fact expelled from the Arab country, his refuge for almost 20 years. The GAP was therefore used as a geopolitical weapon to force Syria to follow Ankara's will. On October 20, 1998, Turkey and Syria signed an important document that sanctioned the definitive easing of diplomatic relations: the Adana Protocol. Following this, the Turks committed to regularly flow water from the Euphrates into Syrian territory while Damascus cancelled Öcalan's political refugee status, forcing him to expatriate again.

The Turkish-Syrian dispute resolved following the signing of the Adana Protocol is emblematic of how the GAP has become a real instrument in the hands of Ankara's diplomacy. A thorny issue that had dragged on with ups and downs for almost twenty years was in fact resolved definitively in the space of a few weeks without firing a shot. Syria is an extremely vulnerable country from a water point of view, in perspective even more than Iraq, where there are respectable water reserves in the central and southern part of the national territory. In addition to the presence of both the Tigris and the Euphrates for large stretches [10], one should take into consideration Lake Buhayrat al-Thartar (2,710 km2), Lake Milh (1,562 km2) and Lake Qadisiyah (over 100 km long).

Fig. 3: Visione aerea del lago Buhayrat al-Thartar

Fig. 4: Visione aerea del lago Milh

Fig. 5: Visione aerea del lago Qadisiyah

These are only the most important fresh water reserves available to Baghdad; in addition, we must consider the myriad of other small lakes and watercourses that contribute to making central-southern Iraq a land that is, if not lush, at least well-served from a water point of view. The opposite can be said for Syria, whose only large river (the Euphrates) flows for a short stretch on the national territory [11] before entering Iraq. Even at the lake level the situation is not the best, given that the only large water basin is artificial and depends for 95% on the inflow from the Euphrates River. We are talking about Lake Assad (610 square kilometers), which came into being following the construction of the Tabqa dam in 1973.

Fig. 6: Visione aerea del lago Assad

Fig. 7: Diga di Tabqa da cui si formò il lago Assad

Such a complex situation on a water level makes Syria a permanent hostage of Turkey, especially following the construction of the GAP. The latter has long ceased to play the role of a simple Anatolian development project; on the contrary, it has progressively established itself as the main geopolitical arrow in the quiver of Ankara, which historically considers the Syrian and Iraqi Near East as a sort of "backyard" on which to exercise an influence far greater than that tolerated by the International Community. Just over a century ago, in fact, these lands were under the direct control of the Ottoman Sultan, who exercised slavish control over millions of people and hundreds of thousands of square kilometers. Today the historical context has decidedly changed; however, the GAP allows Turkey to exercise a very important control function over the entire Middle Eastern region, in some ways comparable to what occurred at the time of the Ottoman millets [12] on Arab soil. This situation is largely due to the lack of international legislation that efficiently supervises the conduct of upstream countries in water management.

In 1997, the UN attempted to remedy this by issuing a document, the UN Watercourse Convention. However, like most conventions, this one also had an essentially programmatic character and lacked the necessary legal force to prevent a State from exercising its will independently. In addition, unlike Syria and Iraq, which ratified the act, Turkey did not do so, effectively ignoring the UN document. And in fact, according to some passages of the convention, ratification by Ankara would have significantly compromised its prerogatives in terms of managing the water flow to downstream countries. In concrete terms, Article 5 of the Watercourse Convention provided for an “equitable distribution” of resources from watercourses for all riparian countries, Article 7 established a “no harm rule” in the management of cross-border rivers, and Article 11 required upstream nations to notify the governments of downstream countries in advance of any development work on shared rivers or lakes. Ratification of the document proposed by the UN would have essentially made the GAP a water infrastructure valid only for internal purposes, effectively erasing the great geopolitical role that it has played and continues to play for Ankara’s diplomacy in the Arab Middle East.

Water at the service of Turkish diplomacy

Ankara has often used its water resources as a diplomatic means to establish profitable relations in the Middle Eastern context. In fact, water has not always been used as an offensive tool to bend recalcitrant countries (such as Syria) to Turkish geopolitical strategies. In this section, we will examine three specific cases, which occurred many years apart, that give a clear idea of how much the Turks use their water wealth in terms of international relations.

Peace Water Pipeline Project

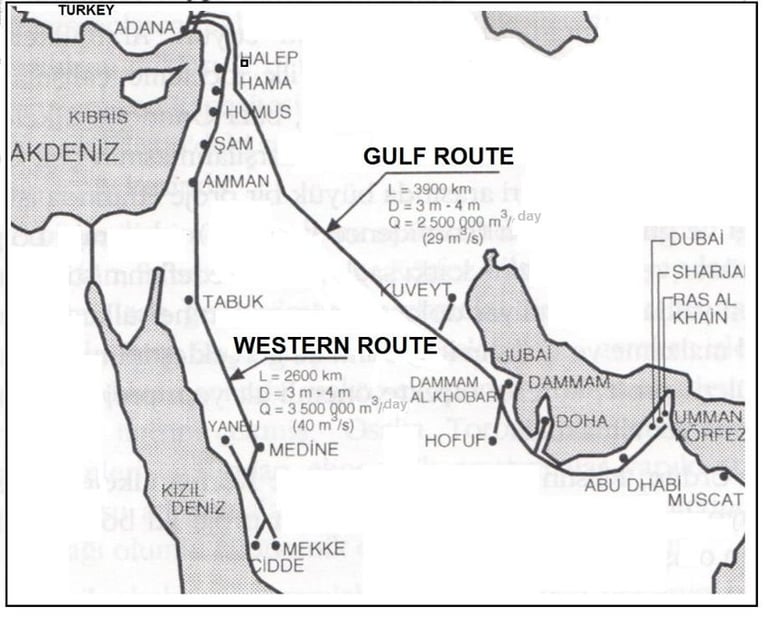

The first case concerns the so-called “Peace Water Pipeline Project”. Theorized by Turgut Özal in the early 1980s, or during the first phase of the construction of the GAP, this large project aimed to build gigantic pipes that would have brought millions of cubic meters of water to many areas of the Middle East where the water supply was (and still is) extremely deficient. As originally conceived, this project would have actually changed the conditions of many people for the better, since it would have essentially made Turkey’s abundant water resources available to millions of Arab citizens. There were two infrastructures to be built: the first, called the Western Route, was 2,650 km long and had a daily water flow of 3.5 million cubic meters. According to the plans, this western pipeline would have its terminus in Mecca and would have passed through Hama, Homs, Damascus, Amman, Yanbu and Medina. Therefore, the countries directly involved would have been Syria, Jordan and Saudi Arabia. The second, called Eastern or Gulf Route, would have extended deep into Western Asia and would have reached Kuwait, Bahrain, Qatar and the United Arab Emirates after having passed through Syria and Jordan. It was longer than the first, almost 3,900 km in total, with a lower capacity, about 2.5 million cubic meters of water per day.

Fig. 8: Le pipelines inizialmente proposte dal governo turco

The estimated cost of this revolutionary and majestic engineering feat was considerable, around 20 billion dollars. The rivers from which the water would have been taken were the Ceyhan and the Seyhan, two waterways that originate and flow entirely in Turkey before flowing into the Mediterranean Sea. Therefore, from an international relations point of view, no particular issues would have arisen, since no coastal state would have complained about a reduced water flow following the use of water to be diverted through the pipes. However, despite the good intentions and the objective benefit that this project would have brought to many Arab families, the Peace Water Pipeline never came to fruition. There were many reasons for this. First of all, its actual construction would have given Turkey enormous power over almost all Middle Eastern countries. Following the finalization of the project, Ankara would have effectively assumed the role of deus ex machina in a matter of essential importance for the Middle East: water supply. In fact, many governments of the countries involved, after an initial lukewarm welcome, have shown little inclination to proceed in the direction indicated by Turkey. Furthermore, the construction of a fully Turkish infrastructure on territories belonging to other countries would have raised questions of national sovereignty, especially because of the Ottoman past. For many analysts, the Peace Water Pipeline would have allowed Ankara to exert great pressure in areas located many kilometers away from its national borders, effectively establishing a geopolitical influence that had not been seen since the time of the Ottoman sultans. Numerous questions also arose on the cost front, since the construction of the pipelines would have entailed a significant outlay especially for the Gulf countries. According to Ankara's plans, in fact, the rich Gulf monarchies would have had to bear almost all of the construction costs. In essence, the Turks aimed to exponentially increase their influence in the region in the face of a very modest financial commitment.

Bahrain and Qatar soon withdrew from this project, which was considered excessively costly on an economic level; Saudi Arabia also showed itself to be extremely skeptical about the actual feasibility of the Peace Water Pipeline. Alternatively, Riyadh proposed to increase the use of desalination plants [13]. In this way, according to Saudi technicians, the costs would have been much lower and the Middle Eastern geopolitics would not have been altered, the developments of which would have been unpredictable for the following decades. Therefore, for a whole series of reasons attributable mostly to the political and economic sphere, the Turkish project was not realized.

Manavgat Project

The second case examined in this report concerns a significant diplomatic rapprochement between Turkey and Israel precisely through an agreement for a water supply. Turkish foreign policy has never renounced a close collaboration with the Jewish state, indeed, in some cases it has convincingly urged it, in particular with regard to the agricultural and water sectors. Israel is currently one of the countries that suffers the least from water stress in the entire Middle Eastern region, which as we know, is often subject to moments of considerable pressure and tension due to serious cases of water scarcity. The main reason that has effectively made Tel Aviv immune to problems related to water supply lies in the massive use of latest-generation desalination plants that guarantee the Jewish state over 60% of its needs in terms of water for domestic use. Starting in 2008, Israel began to invest a lot of resources in the production of equipment capable of making sea water usable. The Zuckerberg Institute for Water Research, one of the country's main research centers, has been instrumental in this sense, providing studies, engineering solutions and strategies that have effectively transformed a semi-desert state into a place where the presence of water can easily be defined as abundant.

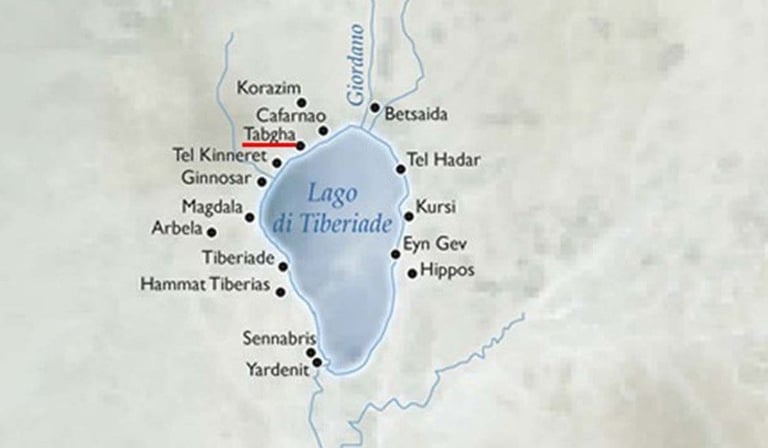

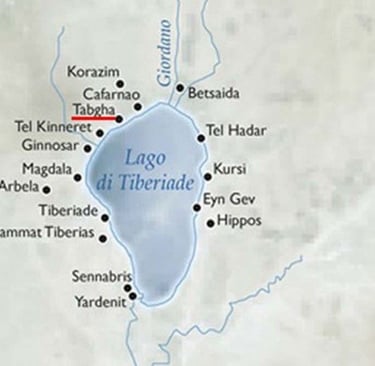

However, until a few decades ago Israel was not doing so well from a water point of view. The year 2008 was a watershed year, since until that moment a very serious and long water crisis had been taking place that had brought the economies and societies of many Middle Eastern states to their knees. A drought that had lasted for about a decade had scorched the Fertile Crescent, causing enormous hardship. Israel's largest source of fresh water, Lake Tiberias, had fallen almost to the limit of the "black line", below which the lake would have suffered irreversible damage in terms of water capacity. To deal with this dramatic situation, restrictions on the use of water were imposed, and many farmers lost

Fig. 9: Lago di Tiberiade

Fig. 10: Stato di Israele

The water crisis that Israel was going through could have caused even more damage if the Manavgat Project had not been implemented. In essence, the Jewish state had agreed with Turkey a diplomatic agreement according to which Ankara committed to sending tankers full of water to the Israeli coasts in order to mitigate the ongoing water supply crisis. The name of the project derives from the Turkish city of Manavgat, from which gigantic ships or floating containers towed by tugboats, possibly escorted by the navy, would have departed towards Israel. Turkish water would also have supported Jordan [14] and Palestine, which also suffered from a worrying shortage of water for both domestic use and at the production level. The agreement was signed in July 1999, when Suleyman Demirel, then president of Turkey, went to Jerusalem to formalize the details. A couple of years later, once all the necessary diplomatic procedures had been completed, the then Israeli Foreign Minister David Levy also officially announced that Turkey would commit to supplying the Jewish state with approximately 50 million cubic meters of water per year. The supply would begin in the summer of 2001.

The Manavgat Project brought Turkey and Israel even closer diplomatically. Despite some Turkish declarations reiterated over time in favor of Palestine, the relations between these two regional powers have historically been very close. Since the time of the Ottoman Empire, in fact, Turks and Jews have established fruitful relations. It was Suleiman the Magnificent who invited the Jewish communities persecuted and expelled from Spain to settle in Istanbul and start a new life at the sultan's court. It was within the borders of the Ottoman Empire that numerous communities of Jewish origin flourished, first and foremost the large and flourishing Jewish community of Thessaloniki, a city of strategic importance for the Sublime Porte. Even today, both in Istanbul and Thessaloniki [15], there are many descendants of those families who found refuge with the Ottomans. The water agreement signed between the twentieth and twenty-first centuries once again sanctioned the great friendship between these two peoples.

The “friendship dam” in the Province of Hatay

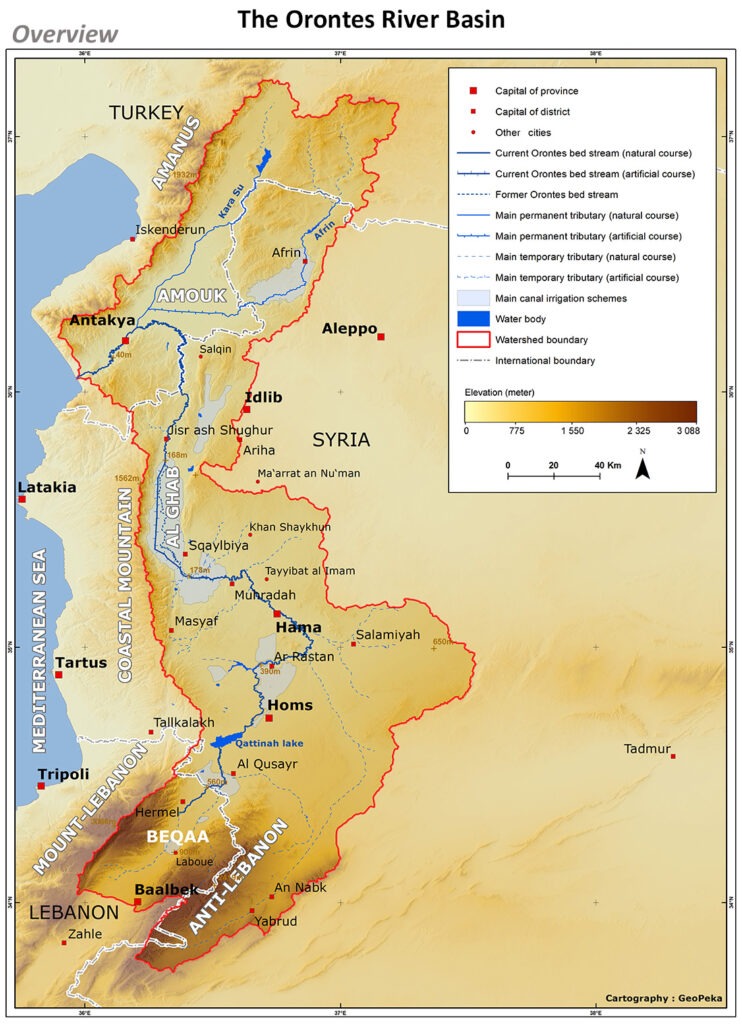

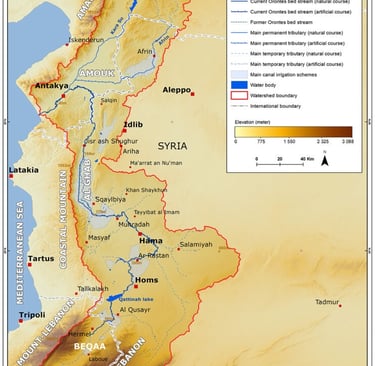

The third and final case under examination concerns an unexpected diplomatic rapprochement that occurred between Turkey and Syria precisely by virtue of cooperation in water matters. We are talking about the project to build a joint dam on the Orontes River, a watercourse that is neither particularly important nor large in terms of extension. The total length of the river is 404 km, of which 38 km flows in Lebanon, 280 km in Syria, 27 km along the Syrian-Turkish border and 59 km in Turkey. However, the significance of the river lies in its geographical location. It is a transboundary river between Turkey and Syria, which, before flowing into the Mediterranean Sea, flows through the province of Hatay. The latter is currently part of the sixty-third province of the national territory of Turkey; however, the status of this territory has been controversial for many years. During the Ottoman rule, Hatay was part of the Aleppo Vilayet in Ottoman Syria. After the First World War, Hatay (then known as Alexandretta) became part of the French Mandate of Syria, as the Sublime Porte had ceased to exist following the disastrous outcome of the conflict. Under the new European administration, Alexandretta was confirmed as an official Syrian territory in the Treaty of Lausanne (1923), agreed by Mustafa Kemal Atatürk, the future leader of the Republic of Türkiye.

Fig. 11: Provincia di Hatay

Fig. 12: Bacino idrico del fiume Oronte

In 1937, after a period of border disputes between Syrian soldiers and Turkish troops, Atatürk obtained an agreement with France through which Alexandretta was recognized as an independent state; two years later in 1939, Hatay, which in the meantime had been renamed the Republic of Hatay, was annexed to Turkey as the sixty-third Turkish province following a controversial referendum [16].

Starting from the second post-war period, diplomatic relations between Turks and Syrians were in fact negatively marked by the Hatay affair. Following the forced annexation of the Syrian province by Ankara, an irreparable wound was created at a diplomatic level between the two Middle Eastern nations. This wound became increasingly gangrenous over time, and then led, as we have just seen, to heavy tensions in bilateral relations. The Adana Protocol signed in 1998 was the first substantial diplomatic rapprochement between the two countries after decades of ill-concealed mutual suspicion. A few years later, Turkey and Syria began a new positive phase in their institutional relations, once again focused on water issues. In 2004, after having signed two important financial agreements [17], a pact was signed for the construction of the so-called “friendship dam”, a large shared water infrastructure on the Orontes River. The choice of the latter was not made by chance. First of all, it is a border watercourse and not a simple cross-border river. On a symbolic level, this testifies to a great desire for collaboration to overcome an extremely problematic past in terms of bilateral relations. Furthermore, the construction of the dam in the province of Hatay, which had been the subject of disputes for decades, had as its aim the definitive overcoming of a long period of tension.

Despite its undoubted symbolic value, the dam would have brought real economic and water management benefits to both countries. Turkey, after regulating the course of the Orontes, would have prevented the seasonal floods of the river that threaten to flood the Amik plain every year, where Hatay International Airport is located. Syria, for its part, would have enjoyed another important water resource in the north of the country which, as we know, depends almost entirely on the Euphrates River. Urban centers of great importance such as Aleppo itself, the second largest city in Syria in terms of population, would therefore have been able to count on another source of water for their supply, avoiding stressing the feeble resources coming from the only large river in the country. From an economic point of view, Syria would have also had undoubted benefits. The costs of the “Friendship Dam”, approximately 550 million Turkish lira [18], would have been entirely borne by Turkey, while Damascus would have had to bear only the costs of expropriation for what concerns the Syrian territory.

Despite the renewed good relations between the two nations and the various benefits that the dam would have brought in many respects, this project did not come to fruition. Following the outbreak of the Syrian civil war in 2011, which had its bloodiest developments in the north of the country, the construction of the “Friendship Dam” was suspended. The violence, the great uncertainties due to the state of war, the generalized chaos have in fact prevented the construction of an important water infrastructure. At the moment, tensions in Syria are much more contained than some time ago; however, the works for the definitive construction of the dam have not yet resumed.

Conclusion

In the coming years, the role of water in international relations will become increasingly crucial, especially in some areas of the world subject to ongoing water crises. The Middle East is one of these. It is one of the most complex regions from a geopolitical point of view; there are ethnic conflicts, sectarian tensions, religious fundamentalisms and bitter conflicts between sovereign nations. However, in the near future many analysts believe that the fiercest clashes between Middle Eastern peoples and states will occur precisely because of water, an indispensable resource not only at a productive and economic level but above all for human life. The arid and dry climate, combined with the absence of abundant water reserves for most countries and constant population growth constitutes the perfect combination in this sense. Turkey, after a few decades of delay, seems to have understood the great role that water will play in the future. The large investments made in Anatolia for the construction of the GAP demonstrate how Ankara considers its water wealth to be strategic, especially when compared to the difficult situation in the Arabian plateau and the Near East.

_______________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________

[1] Cfr. Bruno Cianci, Sultani e infrastrutture, in «Limes», Vol. 10, 2016, p. 90.

[2] Ivi, p. 91.

[3] L’ultima grande crisi finanziaria turca in ordine di tempo risale al 2018, quando nel Paese a cavallo tra Europa ed Asia si verificò un mix di eventi decisamente preoccupanti. Nel concreto, in poche settimane sopraggiunse un crollo del valore della lira, a cui fece seguito un aumento dell’inflazione e un incremento dei costi di finanziamento per l’accesso al credito. Tutto ciò comportò un preoccupante aumento delle insolvenze sui prestiti che, in un Paese tradizionalmente debole a livello finanziario, rischiava di causare danni irreparabili ad interi settori economici. Per ulteriori dettagli si rimanda a Flavio Bini, Turchia, nuovo crollo della lira. Erdogan: “Gli Usa ci pugnalano alle spalle”, in «Repubblica», 13 agosto 2018.

[4] Le riforme che realizzò Mustafa Kemal, futuro padre della nazione turca, furono molte e abbracciarono più campi. Oltre al già menzionato sviluppo ferroviario, egli provvide a cambiare molti aspetti del Paese, soprattutto a livello socioculturale. Per citare alcune delle riforme più importanti, si pensi che rese obbligatorio per la prima volta l’uso del cognome per i cittadini turchi, adottò l’alfabeto latino (con l’aggiunta di 6 lettere), estese il voto alle donne, rese la Turchia una nazione sostanzialmente laica. Per far ciò, dovette lottare assiduamente contro le frange più conservatrici della società. Dunque, lo sviluppo delle risorse idriche non trovò un grande spazio durante il suo governo che, tutto sommato, non fu neanche molto lungo (1923-1938).

[5] Tra i centri urbani di livello solo Diyarbakır, peraltro a grande maggioranza curda, presenta uno sviluppo industriale accettabile.

[6] Per ulteriori dettagli, cfr. Mark Dohrmann & Robert Hatem, The Impact of Hydro-Politics on the Relations of Turkey, Iraq, and Syria, in «The Middle East Journal», Vol. 68 Issue 4, pp. 567–583, 2014.

[7] Concretamente, l’Operazione Shah Eufrate (2015), l’Operazione Scudo dell’Eufrate (2016-17), le Operazioni nel Governatorato di Idlib (2017-2018) e l’Operazione Ramoscello d’Ulivo (gennaio-marzo 2018). Per ulteriori dettagli si rimanda a Rashida Foulani, Turkey’s military operation in Syria: All the latest updates, in «Al-Jazeera English», ottobre 2019.

[8] A partire dal dicembre 2019, mercenari al soldo di Ankara sono intervenuti per supportare il governo di Al Serraj nella lotta contro le forze del generale Haftar. La presenza turca sul territorio libico non si vedeva dal 1911 quando, in seguito alla guerra italo-turca, gli Ottomani furono costretti a lasciare un importante presidio della Sublime Porta a vantaggio delle regie truppe di Roma. Per ulteriori dettagli si rimanda a Nicola Labanca, La guerra italiana per la Libia 1911-1931, Il Mulino, Bologna, 2011.

[9] È il secondo esercito numericamente più rilevante della NATO dopo quello degli Stati Uniti.

[10] Non a caso, l’Iraq è erede della Mesopotamia, letteralmente la “terra tra due fiumi”. In passato, proprio il Tigri e l’Eufrate sono stati la causa principale della cosiddetta Cradle of Civilization, la “culla della civiltà”.

[11] Il bacino idrografico dell’Eufrate è molto scarno in Siria, dal momento che corrisponde a circa il 7.1 % del totale. Per fare un raffronto, si tenga presente che tale dato in Turchia è del 28.2 % mentre in Iraq del 39.9 %.

[12] I millet erano le suddivisioni amministrative con cui l’Impero Ottomano gestiva le proprie provincie.

[13] Il Centro Studi AB AQUA ha trattato la questione dei dissalatori in Arabia Saudita in un recente report realizzato da Filippo Verre. Per ulteriori informazioni si rimanda al seguente link: https://abaqua.it/le-politiche-idriche-dellarabia-saudita/.

[14] La Giordania è il terzo Paese più povero di risorse idriche al mondo, con un clima arido e semi-secco. Il suo intervallo di precipitazioni varia da 40 a 600 mm all’anno, che già di per sé è molto scarso, e il 92% delle precipitazioni evapora ogni anno. Per ulteriori dettagli si rimanda a Dursun Yıldız, The Peace Water Pipeline and innovative hydro-diplomacy, in «World Water Diplomacy & Science News», Gennaio 2018.

[15] Una volta sotto la giurisdizione greca la città cambiò nome e divenne Tessalonica.

[16] Il referendum con cui venne annessa la provincia di Hatay alla Turchia non fu molto regolare, visto che si segnalarono brogli in quasi tutti i seggi. Inoltre, stando ad alcune fonti, molti immigrati turchi che erano nati ad Hatay ma che risiedevano da molti anni altrove, vennero forzati a tornare dalle autorità di Ankara per votare a favore dell’annessione. Per ulteriori dettagli sulla vicenda si rimanda a Filippo Verre, Water conflicts in Western Asia: the Turkish-Syrian regional rivalry over the Euphrates River, in «Rivista di Studi Politici Internazionali», Vol. 87 Issue 3, pp. 353-376, 2020.

[17] Gli accordi avevano un carattere spiccatamente commerciale, a testimonianza della nuova fase distensiva tra le due nazioni. Nel dettaglio, venne firmato un accordo sulla prevenzione della doppia imposizione fiscale e un accordo sulla mutua promozione e protezione degli investimenti. Cfr. Verre, ivi, p. 363.

[18] Circa 75 milioni di dollari.

Abaqua

Via Cassia, 615

00189 Roma (RM)

© 2024. All rights reserved.

Codice Fiscale: 96584590580