The fragility of water-sharing relations between India and Pakistan

Isabella De Baptistis - May 25, 2025

Figure 2 - Image taken from the website: https://climate-diplomacy.org/case-studies/water-conflict-and-cooperation-between-india-and-pakistan

Figure 1 – The source of the cover image is as follows: https://climate-diplomacy.org/case-studies/water-conflict-and-cooperation-between-india-and-pakistan

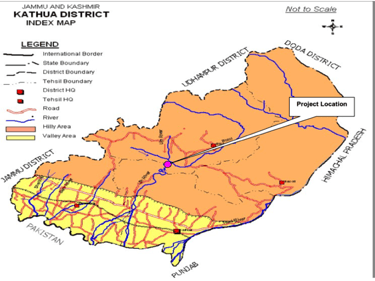

Figure 7 – Location of the Ujh Project

The hydro-strategic rivalries involving India and Pakistan cannot be fully understood without revisiting one of the most significant moments in their shared history, nor without considering the current international context and the respective aspirations and priorities of both nations.

In 1947, the partition of British India into two separate and independent states, India and Pakistan, was officially established. Until that moment, during British rule, Hindu, Sikh, and Muslim communities had coexisted on the Indian subcontinent for centuries, with tensions generally kept under control.

The creation of two states based on religious and confessional grounds granted Indian Muslims (then around 30% of the population) their own independent state, in an effort to prevent potential oppression by the Hindu majority. The birth of the two states was marked by intense tensions and horrific violence, resulting in the mass migration of between 12 and 15 million people.

Since their independence, India and Pakistan have fought three wars (in 1965, 1971, and 1999), along with numerous shorter conflicts and border skirmishes.

The primary focus of these clashes has been, and continues to be, the Kashmir region—India's only Muslim-majority territory, and a region disputed by the two countries since the 1947 partition.

Today, Kashmir is divided into three regions: two under Pakistani administration (Gilgit-Baltistan and Azad Kashmir) and one under Indian administration (Jammu and Kashmir). The region is rich in natural resources and strategically important, particularly in terms of water and mineral wealth.

While the region’s hydrography has ensured a certain degree of water security for India, thanks to the many rivers that flow through it, Pakistan does not enjoy the same hydrological advantage.

The Pakistani region is entirely dependent on the Indus River, the only major river basin in the area capable of sustaining national development. Based on this strategic asymmetry, control over river resources has, for more than half a century, been a source of interstate rivalry and tension between India and Pakistan. The course of the Indus River is primarily distributed between India (39%) and Pakistan (47%), with smaller sections extending into Tibet and eastern Afghanistan (FAO, 2011a)[1].

At the time of the two states’ formation, the border between India and Pakistan was drawn largely in accordance with the natural contours of the so-called Indus watershed (Gardner, 2019)[2].

This delineation favoured India in its control over dams and infrastructure regulating the water flow toward Pakistan. The physical border cuts across many of the river’s tributaries, creating a crucial water management structure under Indian administration that remains a persistent source of bilateral tension.

India’s extensive water infrastructure - including dams and hydroelectric plants - represents not only a valuable source of energy for its economy but also a constant threat to the fragile geopolitical equilibrium of the region. Fears of future water scarcity - exacerbated by national water management policies and polarizing political narratives - give rise to recurrent diplomatic crises between the two states.

On one hand, in India, violent actions perpetrated by the Islamist militant group Jaish-e-Mohammad, which is widely believed to be affiliated with Pakistan, are frequently instrumentalized to justify the deterioration of bilateral relations and even to threaten reductions in Pakistan’s water supply (Al Jazeera, 2019; Roy, 2019)[3]. On the other hand, nationalist Pakistani media outlets often accuse India of intentionally triggering floods within Pakistan, allegedly resulting from unilateral and poorly coordinated water resource management.

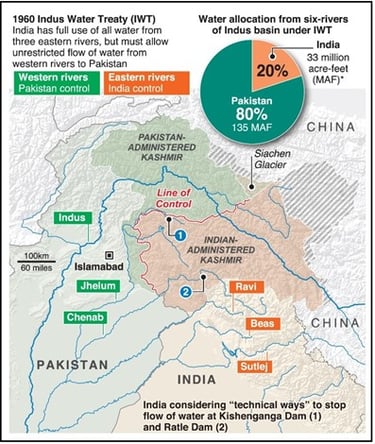

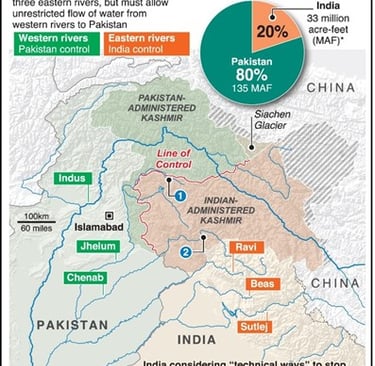

The Indus Waters Treaty: legal guarantor of Peace

Water-related issues in the Indus Basin are primarily governed by the Indus Waters Treaty (IWT), signed in 1960. With the decisive mediation of the World Bank during negotiations - prompted by a 1948 incident in which India halted water supplies to several Pakistani villages - the Treaty established principles for the interstate sharing of the Indus River’s waters in order to prevent water-related conflicts between India and Pakistan.

The World Bank also provided financial assistance to both countries for the construction of water storage and transport infrastructure, enabling the use of supplies that would otherwise have been lost following the enforcement of the agreement.

The Treaty’s twelve articles assign control of the three eastern tributaries of the Indus River - Ravi, Sutlej, and Beas, which eventually flow into Pakistan - to India, while the three western tributaries - Indus, Jhelum, and Chenab - remain under Pakistan’s jurisdiction.

The functioning of the Treaty is based on a cooperation mechanism and the exchange of information between India and Pakistan concerning the use of their respective river systems. This includes biannual meetings of the Permanent Indus Commissioners from both countries and technical visits to worksites on the river sources.

Although the legal framework governing water distribution between the two states has generally been accepted by both parties, the Treaty has come under increasing scrutiny. Key points of contention include India’s development of numerous hydroelectric projects, dam construction, and the resulting alteration of water flows toward Pakistan.

Pakistan challenges both the allocation of control over Indus tributaries and the provisions that have allowed India to legally build infrastructure perceived to endanger Pakistan’s water security.

In parallel, Pakistan has also sought sup

port from its strategic ally China - which upholds Pakistan’s sovereign claims and territorial integrity - in an effort to boost its regional economic influence through the implementation of large-scale development projects, particularly within the framework of the China-Pakistan Economic Corridor (CPEC).

Water as a driver of tension

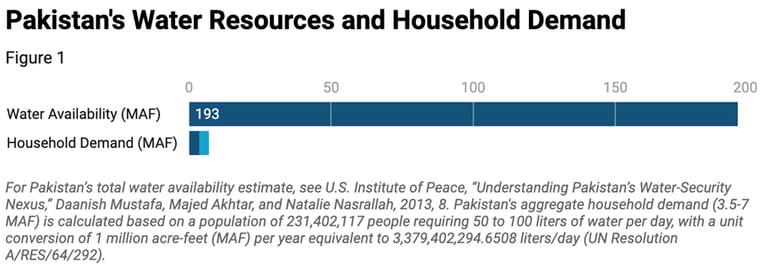

The shared Indus Basin is the second most heavily exploited aquifer in the world; excessive withdrawals pose a long-term threat to water availability throughout the basin. Paradoxically, within the region irrigated by the Indus River, Pakistan ranks among the most water-stressed countries globally. Although Pakistan possesses enough water that could meet the basic needs of its population, millions of Pakistanis still lack access to safe and adequate water supplies. According to the World Health Organization (WHO), a person requires between 50 and 100 litres of water per day to live a dignified life[1]. Based on Pakistan’s population, the country would need between 3.5 and 7 million acre-feet (MAF) of water annually to meet its domestic demand[2].

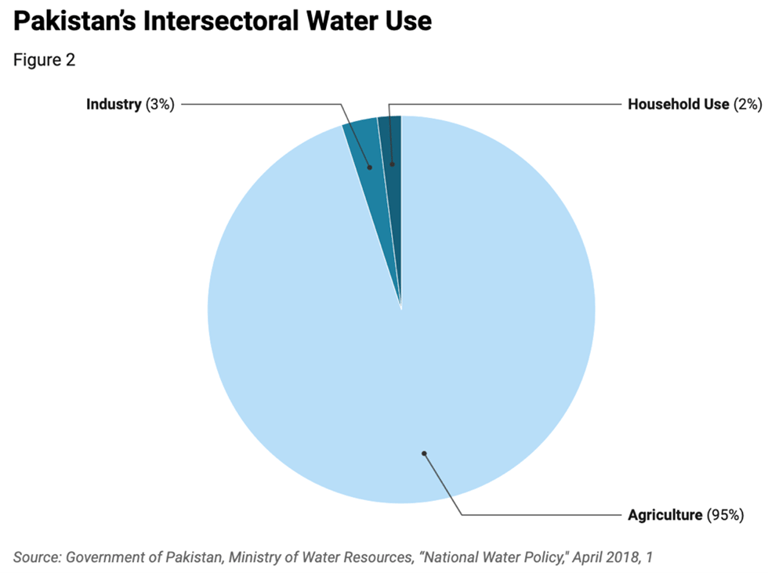

Despite variations in estimates, Pakistan’s collective annual water availability stands at approximately 193 MAF[1]. Unlike India, Pakistan is almost entirely dependent on the Indus River: around 90% of the country's food production and 65% of its employment are tied to agriculture and livestock.

In addition, the southern regions of Pakistan are particularly vulnerable in terms of water supply from the Indus Basin, exposing local communities to the risk of social tensions. Alongside poor water resource management, the impacts of climate change contribute significantly to the emergence of water stress conditions. The Himalayan glaciers, which feed the Indus Basin, are expected to shrink further in the coming years. It is estimated that the flow of the Indus River will decrease by 8% by 2050.

While this reduction may initially lead to a temporary increase in runoff, it will ultimately deplete aquifer recharge over the long term, thereby diminishing the availability of groundwater resources[1].

At the same time, monsoon rainfall patterns are projected to become increasingly erratic in both frequency and intensity, raising the risk of flooding. Such a scenario is likely to intensify political tensions between the two regional powers over water distribution and flow management. Over the years, water has already served as a catalyst for disputes between India and Pakistan. In fact, Pakistan has repeatedly appealed to international institutions over alleged Indian violations of the Indus Waters Treaty, particularly in response to Indian dam construction projects that could alter water flows into Pakistan.

The first major instance occurred when Pakistan requested the World Bank to appoint a neutral expert after raising concerns about India's Baglihar Dam project on the Jhelum River.

According to Pakistan, these hydroelectric initiatives would allow Indian engineers greater control over the river’s flow than what was permitted under the Treaty. However, in 2007, the neutral expert approved India's construction plans[2].

Subsequently, Pakistan once again turned to the World Bank, this time requesting the convening of an arbitral tribunal to adjudicate the legality of India’s Kishanganga Dam on a tributary of the Jhelum River.

In its 2013 ruling, the Permanent Court of Arbitration in The Hague allowed India to complete the project, without explicitly siding with either country[3].

Tensions between India and Pakistan flared again in 2016 following a terrorist attack in the town of Uri, located in the Kashmir region. In response, India cancelled its participation in the scheduled meeting of the Permanent Indus Commission (PIC) [4] and simultaneously convened a meeting to consider amending or even terminating the Indus Waters Treaty.

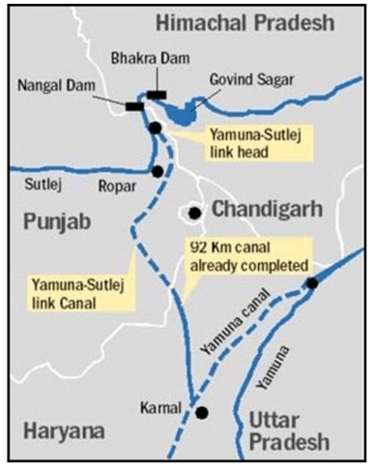

India also accelerated the development of three water infrastructure projects: the Shahpur-Kandi Dam and the UJH project in Jammu and Kashmir, and a second Sutlej-Beas link in the Punjab region

Figure 4 – Intersectoral water use in Pakistan

Figure 5 – Baglihar Hydroelectric Dam

Figure 8 - Shahpur-Kandi Dam

Figure 6 – Construction of Kishanganga Dam

Figure 9 - Sutlej-Beas link project

In 2016, Pakistan approached the World Bank to request the establishment of another arbitral tribunal to assess the legality of India’s construction of the Ratle Dam on the Chenab River, while India advocated instead for the appointment of a neutral expert. Despite the conflicting positions, the World Bank - much to the dismay of Indian officials - decided in 2017 to initiate both processes simultaneously, appointing the key experts in October 2022. Indian authorities subsequently threatened to disregard any ruling issued by the arbitral tribunal

Figure 10 – Ratle hydroelectric Dam

The fragility of the water-sharing relationship between India and Pakistan became even more apparent in 2019, following a terrorist attack in Pulwama (in Indian-administered Kashmir), claimed by the Pakistan-based militant group Jaish-e-Mohammad. The attack resulted in the deaths of 46 Indian paramilitary personnel.

India’s political response was articulated by then Minister of Water Resources, Nitin Gadkari, who threatened to halt the flow of water to Pakistan and publicly denounced the Indus Waters Treaty[1].

However, the Treaty does not allow either party to unilaterally withdraw from the agreement.

Article XII of the Treaty explicitly states: “The provisions of this Treaty may be modified from time to time by a duly ratified treaty concluded for that purpose between the two Governments and shall remain in force until terminated by such a treaty.” On January 25, 2023, for the first time in the history of the agreement, India formally requested a modification of the Treaty through the Permanent Indus Commission. India reportedly asked Pakistan to renegotiate the terms related to dispute resolution mechanisms. This initiative could potentially be used by India as a bargaining tool to exert pressure on Pakistan in the broader context of their bilateral political tensions.

The new crisis in bilateral Water Cooperation

The recent resurgence of tensions between the two countries led India to suspend the Indus Waters Treaty as retaliation for the terrorist attack that took place on April 25, 2025, in Pahalgam, Anantnag district of Indian-administered Kashmir, which killed 26 people. As in 2016, India’s retaliatory measures were swift and severe. The suspension of the Indus Waters Treaty marked yet another attempt to interrupt bilateral cooperation, undermining the shared management of water resources. India’s move was clearly aimed at exerting pressure on Pakistan’s water availability.

The suspension allows India to retain billions of cubic meters of water from the western rivers during high-flow periods - waters that, under the Treaty, should flow to Pakistan. However, India currently lacks the large-scale storage infrastructure and diversion channels necessary to retain such volumes.

India primarily operates run-of-the-river hydroelectric plants, which generate electricity using the river's natural flow without requiring massive dams or large reservoirs to store water. The real risk of the Treaty’s suspension lies in restoring unilateral discretion to each country to modify existing infrastructure or build new facilities that could withhold or alter water flows, thus undermining reciprocal access to this vital resource. Asymmetric distribution of water resources may, in turn, lead to collateral environmental damage, increased water stress, or sudden downstream flooding.

Moreover, the suspension of the Treaty eliminates the obligation for mutual information-sharing regarding water use and infrastructure projects, decreasing transparency and fostering mutual distrust - significantly increasing the likelihood of conflict. Pakistan, being heavily water-dependent, faces serious threats from any substantial decrease in access to Indus waters, which are vital to its survival and development. Pakistan has declared that any attempt to interrupt or divert water flows to which it is entitled will be considered an act of war by India.

This scenario escalated into open conflict on May 6 with the launch of cross-border missile strikes between the two countries. Only a few days later, on May 10, through direct mediation by the United States, India and Pakistan announced a ceasefire, immediately halting military attacks. These were the most serious military confrontations between the two nuclear-armed states in recent years.

This latest episode exemplifies the growing instrumentalization of water as a geopolitical asset governed by the logic of power. The militarization and securitization of water highlight the urgent need to develop a political and diplomatic culture based on win-win cooperation in the management of transboundary water resources - especially within the current geopolitical context of a world fragmented by thirty-one ongoing conflicts.

In this regard, AB AQUA continues to raise national and international awareness of water’s role as a tool for cooperation, sustainable development, and peace. As a symbol of unity, diplomacy, and collective commitment, water represents for us a fundamental starting point for generating lasting and positive change.

The Chinese shadow in Indo-Pakistani hydrostrategy

In this current phase of uncertainty surrounding the management of Indo-Pakistani water resources, it is crucial to consider the geopolitical entanglements between Pakistan and China, which may significantly influence future decisions regarding the Indus Waters Treaty.

India’s unilateral decision to suspend the Treaty may compel Pakistan to accelerate its efforts to construct dams in the Pakistan-administered Kashmir region, leveraging its cooperation with China.

Pakistan and China are already collaborating on major infrastructure projects, including the Diamer-Bhasha, Dasu, and Mohmand dams. Consequently, India’s recent actions may serve as a catalyst to expedite the completion of these hydropower facilities. Since the launch of the China-Pakistan Economic Corridor (CPEC) in 2015, China has invested billions of dollars in infrastructure projects in Pakistan, including in the hydropower sector.

In 2024, the China Energy Engineering Corporation (CEEC) announced a significant investment program in Pakistan, focused on hydropower and renewable energy, as well as electricity transmission line projects. China committed to the construction of the 1.5 billion USD Azad Patan hydropower plant and the 1.9 billion USD Sikhi Canari hydropower project.

Just last April, China expressed strong interest in investing in the development of a desalination plant at Pakistan’s Port Qasim, aimed at converting seawater into potable water for industrial and domestic use. The initiative seeks to diversify Pakistan’s water sources and mitigate the impacts of extreme water stress scenarios.

In the long term, India will therefore need to take into account the emerging Sino-Pakistani alliance in the water sector when formulating its hydrostrategic approach toward Pakistan.

This evolving dynamic could alter regional power balances and potentially reduce New Delhi’s ability to exert strategic pressure on its neighbour.

At best, India might attempt to leverage this new configuration to renegotiate the treaty with Pakistan. However, any unilateral initiative risks strengthening Islamabad and Beijing’s partnership, further undermining the cooperative spirit that the Indus Waters Treaty has historically embodied.

Conclusions

The analysis of water management between India and Pakistan highlights the urgent need to modernize and adapt the Indus Waters Treaty to present-day climatic realities and environmental policies.

Signed in 1960, the Treaty did not account for the effects of climate change on overall water availability or its distribution in the region. In today’s context, it would be highly desirable for the Treaty to incorporate preventive measures to address natural disasters, which are becoming increasingly frequent and severe in this area.

Moreover, the Treaty does not impose any limits on the number of dams India may construct on the Indus Basin, nor does it provide clear guidelines on the allocation of water between the two states.

This absence of defined water quotas opens the door to potential Indian overexploitation.

India’s widespread development of dams and hydropower facilities represents not only a strategic energy advantage but also a constant threat to the fragile regional geopolitical balance. Despite this, the proposed reforms to improve the Treaty’s effectiveness remain unimplemented. The true threat lies in the uncertainty of what the future holds, and the dangers posed by discussions around the suspension of water flows, which could provoke further crises in the coming months and years.

The Treaty’s normative shortcomings underscore the urgent need for international legal frameworks to govern the management of transboundary rivers and lakes - especially in light of persistent political and social tensions between India and Pakistan that weaken the Treaty’s effectiveness and jeopardize broader cooperative relations.

As outlined in this report, the historic rivalry between the two countries - rooted primarily in territorial disputes over Kashmir - has progressively transformed into a struggle over water resources.

In Pakistan, water-related issues elicit strong and continuous public engagement, often fuelling anti-Indian narratives. In contrast, India’s investment in critical water infrastructure holds various strategic meanings: it ensures running water for households, supports irrigation for agricultural lands, provides energy, and contributes to national technological advancement and modernization.

Three years after signing the Treaty, Indian independence leader Jawaharlal Nehru inaugurated the Bhakra Dam on the Satluj River, presenting it as “a temple of modern India” (1963)[2].

Today more than ever, India recognizes the strategic return of managing water resources through a political-economic lens. This approach serves multiple national interests: securing internal development, addressing challenges in equitable water access for its vast population, and projecting India as a mature and forward-looking nation on the global stage—a goal in line with its ambitions for a more influential geopolitical role.

At the 2023 United Nations Water Conference, Minister Gajendra Singh Shekhawat announced that India plans to invest over 240 billion USD in the water sector[3]. In collaboration with private actors, start-ups, and water user associations, India is also implementing the world’s largest dam rehabilitation program to build storage infrastructure vital for climate resilience.

India’s expanding water development vision, coupled with a global multilateral crisis and the absence of binding international legislation on transboundary water management, urges the strengthening of bilateral cooperation mechanisms. Such collaboration could lay the foundation for a new basin management model, encapsulated in the neologism “Industan”[4].

This term calls for viewing and managing the Indus Basin as a single, integrated, and shared resource to prevent hydro-diplomatic ruptures that could lead to a broader deterioration of bilateral relations and jeopardize the fragile ceasefire recently achieved in Kashmir.

__________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________

[1] Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations, “AQUASTAT, FAO’s Global Information System on Water and Agriculture”, 2011: https://www.fao.org/aquastat/en/countries-and-basins/transboundary-river-basins/indus

[2] Climate Diplomacy, “Water conflict and cooperation between India and Pakistan”: https://climate-diplomacy.org/case-studies/water-conflict-and-cooperation-between-india-and-pakistan

[3] Aljazeera, “India reiterates plan to stop sharing water with Pakistan”, 2019: https://www.aljazeera.com/news/2019/2/21/india-reiterates-plan-to-stop-sharing-water-with-pakistan

[4] United Nations, Resolution A/RES/64/292, “The Human Right to Water and Sanitation”, 2010: https://www.un.org/waterforlifedecade/pdf/human_right_to_water_and_sanitation_media_brief.pdf.

[5] Uzair Sattar, “Pakistan’s Political Economy perpetuates its Water Crisis”, STIMSON, 2023: https://www.stimson.org/2023/pakistans-political-economy-perpetuates-its-water-crisis/

[6] U.S. Institute of Peace, “Understanding Pakistan’s Water-Security Nexus”, 2013: https://www.usip.org/sites/default/files/PW88_Understanding-Pakistan’s-Water-Security-Nexus.

[7] Dhanasree Jayaram, “Why India and Pakistan need to review the Indus Waters Treaty”, Climate Diplomacy, 2016: https://climate-diplomacy.org/magazine/cooperation/why-india-and-pakistan-need-review-indus-waters-treaty

[8] Daniel Haines, “India and Pakistan are playing a dangerous game in the Indus Basin”, United States Institute of Peace, 2023: https://www.usip.org/publications/2023/02/india-and-pakistan-are-playing-dangerous-game-indus-basin

[9] idem

[10] Commissione bilaterale composta da funzionari dell'India e del Pakistan, istituita dal Trattato.

[11] Debayan Roy, “Can India unilaterally revoke Indus Water Treaty with Pakistan”, News18, 2022: https://www.news18.com/news/india/can-india-revoke-indus-water-treaty-unilaterally-news18-explainer-2045325.html

[12] Aljazeera, “India reiterates plan to stop sharing water with Pakistan”, 2019: https://www.aljazeera.com/news/2019/2/21/india-reiterates-plan-to-stop-sharing-water-with-pakistan

[13] Adriano Marzi, “L’acqua contesa tra Pakistan e India”, Nuova ecologia, 2019: https://www.lanuovaecologia.it/acqua-contesa-tra-pakistan-e-india/

[14] Smart Water Magazine, “India to invest over $240 billion in water sector”, 2023: https://smartwatermagazine.com/news/smart-water-magazine/india-invest-over-240-billion-water-sector

[15] Institute for Water, Environment and Health, dell’Università delle Nazioni Unite (UNU-INWEH) ha pubblicato, su Springer, il report “Imagining Industan”.

Abaqua

Via Cassia, 615

00189 Roma (RM)

© 2024. All rights reserved.

Codice Fiscale: 96584590580